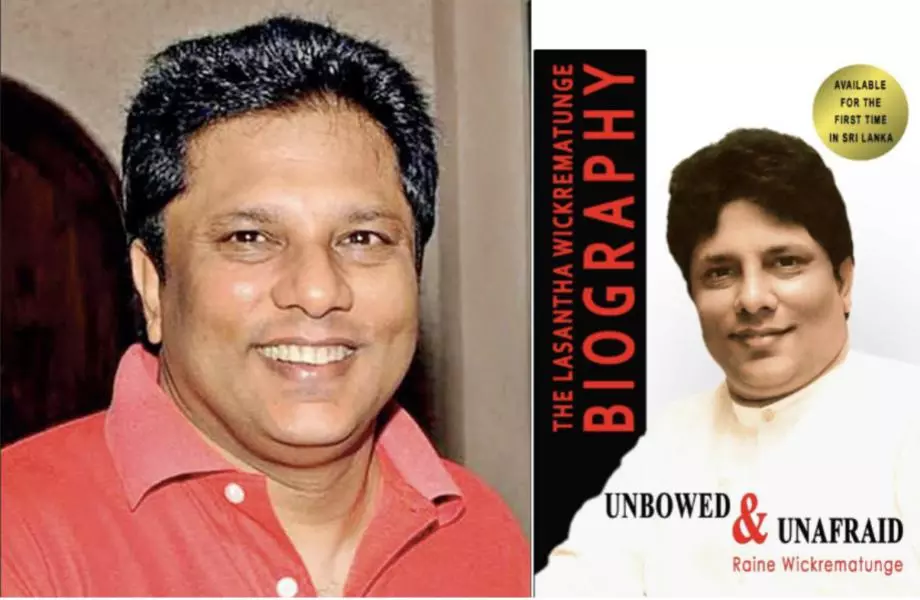

‘Unbowed and Unafraid’ review: Journalist-martyr whose writings predicted Sri Lanka’s fall

Raine Wickrematunge's book showcases how societies get destroyed when majoritarianism is used as a brutal weapon in the garb of nationalism

If the 2022 mass movement in Sri Lanka which ousted dictator President Gotabaya Rajapaksa were to be credited to a single individual, it must be a journalist whose courageous writings warned of the island nation’s slow slide into a corrupt fiefdom that has today reduced it to a failed state.

Unfortunately, Lasantha Wickrematunge did not witness the street protests that forced Gotabaya to flee the country in scenes reminiscent of the Iranian revolution. Months before Gotabaya and his President brother Mahinda Rajapaksa crushed the LTTE in May 2009, Lasantha was silenced in a brutal manner on a Colombo street by killers linked to the state.

Lasantha’s crime? Call him an idealist or a lone crusader, he campaigned unceasingly not only against nefarious governments and shady leaders but a rotten culture of corruption, cronyism, racism and impunity which had come to mark Sri Lanka — diseases which have not gone away. He refused to compromise. No amount of cajoling and temptations could make him change tracks. He did not care despite multiple threats.

Revealing the ugly truths

Lasantha’s journalism began in a News Desk as a trainee. Once he shifted to reporting, he easily cultivated sources, first in the police and courts and later in various levels of politics, in which he dabbled for a while before deciding that journalism was his true calling.

Also read: Murakami’s latest novel has walls as metaphor for physical, emotional barriers

He flourished as a journalist when he began writing a political column in The Sunday Times under the pseudonym Suranimala. For long, only a handful knew the identity of the writer who seemed to have sources almost everywhere and didn’t spare anyone. The column became a talking point across Sri Lanka.

His contacts in the government, opposition, legal fraternity (Lasantha was also a trained lawyer), private sector, defence forces and diplomatic circles were more than willing to share information with him. But when the body of another popular journalist, Richard de Zoysa, was washed ashore after murder, Lasantha and his wife left for Australia with their baby.

When he returned to Colombo, he joined The Sunday Leader, a new weekly newspaper that catapulted him to overarching fame. He immersed himself in investigative journalism of the highest order, exposing the state’s serious transgressions, ministerial corruption, crooked arms deals, irregular tender procedures, corporate criminality and links between the state and the underworld.

No media establishment in Sri Lanka had until then so boldly published stories that rocked the state, military establishment, judiciary and other powerful institutions. A blood-soaked civil war was on in Sri Lanka. Revealing the ugly truths in the military establishment then was labelled ani-national, notwithstanding the serious damage it was causing to the economy. Naturally, Leader’s readership and circulation soared.

Lasantha began receiving threats around one year into the Leader’s publication. Initially, there were ominous telephone calls, some threatening him with dire consequences. Then came letters. The first of it was a note tossed into a dustbin that ordered him to stop writing or face the inevitable (read death). Soon came a vicious physical attack on him; he would have been killed had his wife not thrown herself on him. It was 1995. Lasantha was not intimidated.

Aggressive brand of journalism

President Chandrika Kumaratunga, who wore the cloak of a liberal, hated Lasantha. In response to requests to make public her degree certificates from Paris, she called him a “worm”. She used every opportunity, in private and public, to launch scathing attacks on the “muck-raking, rag-sheet journalist”.

Lasantha realised that government sleuths, goons or both were on his trail; suspicious characters often hovered nearby. In 1998, gunmen targeted his house, firing away some 40 cartridges from a T-56 rifle. Lasantha and his wife had returned home 15 minutes earlier — and so survived.

Also read: What ho! With PG Wodehouse’s sensitivity makeover, we’ve gone too far in censoring classics

If Kumaratunga was bad enough, her successor Mahinda Rajapaksa was far worse. By then, Lasantha had also become a television personality but continued his aggressive journalism. Naturally, cracks appeared in the old relationship between Mahinda and Lasantha once the former became the prime minister. As Lasantha kept exposing corruption in a government now dominated by the Rajapaksa clan, Mahinda turned ferocious. One day, an armed gang broke into the Leader press in Colombo and set bundles of newspapers on fire.

Shortly after being sworn in as president in November 2005, Mahinda threatened Lasantha on phone. “I will stop only when I have destroyed you… You don’t know who Mahinda Rajapaksa is… I will destroy you.” Lasantha promptly wrote about it and informed all and sundry. And in a prophecy that would ominously come true, Lasantha warned in his paper: “He (Mahinda) has proved himself a man who will soon make this country a banana republic rather than a democratic one.”

After a second commando-style attack on the newspaper press, which came after Lasantha was harassed at the airport, the editor wrote a stinging piece to underline who his targets were: “Political rogues in saintly clothes… death merchants who preach patriotism…unqualified profligate wastrels… brazen thugs… pious hypocrites… state officials who have diddled billions of rupees of state funds.”

Attacks on journalists became a regular feature in Sri Lanka, making the country one of the most dangerous places for free media. All through 2008, apart from everything else, Lasantha highlighted abductions by white colour vans linked to the military-intelligence set-up, brazen human rights violations and duplicity in the war against the LTTE.

‘Then They Came for Me’

By the end of 2008, Lasantha appeared to be a worried man although he remained steadfast in his journalism. In October that year, president Mahinda called him a “terrorist journalist”. In late December, Lasantha told his brother these chilling words: “When Kilinochchi is re-taken is when they will kill me.”

Also read: Harry Potter, 15 years on: From frenzied anticipation to franchise fatigue

On January 2, 2009, the Sri Lankan military captured Kilinochchi, dealing a huge blow to the LTTE which had until then used the northern Tamil town as its administrative headquarters. That January Lasantha was certain that an attack on him was imminent. Death threats continued. Thirteen days before he was killed, he called his wife in Australia and told her that he was writing his will.

On January 8, 1990, as Lasantha — looking youthful despite his 50 years — drove to his office, he noticed in the rear-view mirror of his Toyota that men dressed in black and on motorcycles were whizzing in and out of range for some time. He called a few friends to say he was in danger. Suddenly, a bus ahead of him came to a halt, forcing him to stop. The killers on motorcycles immediately pounced on the cornered man, shattered the windows and jabbed the editor with a sharp-edged weapon, leaving him to die writhing in pain.

As Sri Lanka plunged into sorrow and international condemnations poured in, the government was shaken up. Little did anyone know that a deafening bomb was to follow. It came in the form of a stinging editorial which Lasantha had penned predicting his own untimely death. Titled “Then They Came for Me”, it was published three days after he was murdered.

“Terror, whether perpetrated by terrorists or the state, has become the order of the day,” he wrote, painting a grim picture of Sri Lanka, “Today it is the journalists, tomorrow it will be the judges.” He spoke about the attacks on him and the lack of any serious inquiry. “When finally I am killed, it will be the government that kills me.”

To make sure no one is in any doubt as to who he felt would order his killing, Lasantha referred to Mahinda by name. “In the wake of my death I know you will make all the usual sanctimonious noises and call upon the police to hold a swift and thorough inquiry. But like all the inquiries you have ordered in the past, nothing will come of this one, too… In the name of patriotism, you have trampled on human rights, nurtured unbridled corruption and squandered public money like no other President before you… I also know that you will have no choice but to protect my killers: you will see to it that the guilty one is never convicted.”

Exposing decades of brazen corruption

Lasantha was proven posthumously right. The killers were never caught. It did emerge from various sources that they were soldiers linked to a secret group called Tripoli Platoon. Even as the Lasantha family was in mourning, Mahinda denied any involvement. He tried to pin the blame on former army chief Sarath Fonseka after the latter rebelled against him. Later, Gotabaya Rajapaksa took over the presidency and made Mahinda the prime minister. How they got booted out is history.

Also read: ‘Beef’ review: A darkly humorous exploration of road-rage-fuelled feud, repressed grief

Besides being a fearless journalist, Lasantha was also a humanist, one who was concerned about Sinhalese majoritarianism which enjoyed the repeated merciless bombings of Tamil areas during the war against the LTTE. The Sri Lankan society realised the danger of allowing officially-sanctioned murderers to bloom when the monsters began devouring prominent lights of the Sinhalese society. Lasantha was neither the first nor the last journalist to die at the hands of those who looted Sri Lanka. A power-drunk Gotabaya told BBC: “Who is Lasantha Wickrematunge? There are killings all over the world.”

Sri Lanka is still not out of the woods. While Gotabaya is gone (hopefully for good), Mahinda lurks behind the presidency of Ranil Wickremesinghe. The decades of brazen corruption (frequently exposed by Lasantha) have taken a heavy toll. Sinhalese majoritarianism reigns supreme, unable to offer even perfunctory political concessions to the Tamils. Muslims have been vilified. No one has been punished in any meaningful manner for the scores of brutal murders across the length and breadth of Sri Lanka. Does the island nation have a better future?

You will get some answers from this book, which was first published in a condensed form in 2013 but could not be sold in Rajapaksas’ land. This is an enlarged edition, available in Sri Lanka too, and brought up to date. Every South Asian should read it to know how once stable societies get destroyed when majoritarianism is used as a brutal weapon in the garb of nationalism.