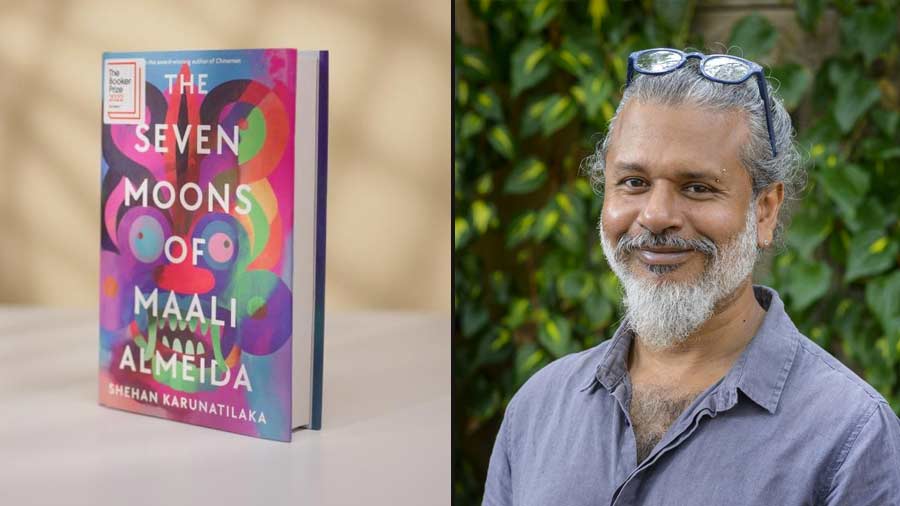

‘The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida’ review: When paradise turns to purgatory

Sri Lanka has long been known or described here in India as a paradise. As if another paradise up north, Kashmir, wasn’t enough. Hanging like a teardrop in the eastern tip, as if trying to cosy up to India for support, the small island had lots that would qualify it as a paradise.

But, during the last 50 years, it has gone through what no single island has gone through: anarchy, war, destruction, collapse of the state itself, and to add to it all, nature’s wrath in the form of tsunami. It is not something that we would wish upon any place with a Buddhist majority since we believe that Buddhists are peace-loving and have no ulterior motives in whatever they do. But in Sri Lanka and Burma up north, where Buddhists are a majority, they have launched large-scale attacks against the minority. For that Sir Lanka, with its Sinhala Buddhist majority, has had a terrible price to pay.

A country at war with itself

It is in that battered Sri Lanka that Shehan Karunatilaka places his second novel, which has won the 2022 Booker Prize. Totally anarchic, the novel trawls the underbelly of a country at war with itself: Sinhala state versus Tamil minority versus the anarchic Janata Vimukthi Perumana or JVP, and as if that was not enough, Tamils versus Muslims, Buddhists versus Muslims and various freelance and LTTE bombers versus each other and the state. For total anarchy there could not have been any better paradise.

Also read: Sri Lankan author Shehan Karunatilaka wins Booker Prize

Chats with the Dead (Penguin Random House India), published as The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Sort of Books in the UK, is located in purgatory. It’s a great device by the author because the dead tell their tales to each other and the narrative moves between the past happenings: Down There, interlaced with various happening in purgatory or In Between, where all the dead, including the anti-hero or news photographer Maali Almeida, who has all the proofs of killings and bombings and plane crashes, activists, politicians and soldiers wait for their Ears to be checked before being pushed towards the Light. Dripping with sarcasm and anger, the novel is also a death certificate for the Sri Lanka we knew not too long back.

We, as readers, are concerned not with ear checks, but with history checks and the narrative provides quite a few, especially the much-talked-about feud between the LTTE chief Prabhakaran and the his then deputy Mahata or Colonel Gopalaswamy in the novel. Many journalists are named with a slight twist to their names, including Anita Pratap, who got an interview with Prabhakaran for Time magazine).

By Shehan Karunatilaka, Penguin Random House India

When everything has slipped into anarchy , anything can happen as part of daily routine. Maali had left behind some photographs and if at all any action takes place in the novel, it is the search for the envelopes of damning films and photographs which are finally exhibited by two Tamil activists, who are believed to be agents of Mahata operating under various names. Running parallel to this is homosexuality since Maali is queer. Between dangerous news assignment, he manages to find boys and even Armymen and rub their crotch as a beginning to their friendship. Finally, Maali pays the price for being a queer when the father of his partner DD confronts him before killing him, saying: “I didn’t send my son to Cambridge to come back and get Aids from a queer.”

Also read: Booker finalist Shehan Karunatilaka explores privilege and class in new book

The ghosts of the past

So what’s the deal in the novel? Well, even if Maali was not a queer, the novel would have worked, for it does a wonderful job of laying bare the underbelly of a Buddhist state that is paradise for some, bombing yard for others, killing fields for the army, and where everyone is part of one war or another. By placing his characters in Purgatory or In Between, Shehan is telling us that Sri Lanka itself is purgatory for many, hanging between life and death or near-death or after-death. “Being a ghost isn’t that different to being a war photographer,” the narrator says. Lanka has become purgatory, but there is some hope:

“If you could end this war once and for all, what is the acceptable number of civilians?

None.

That is why this war will go on for ever.

Nothing goes on for ever. That is one thing Buddha got right.”

Was Shehan writing an obit for the paradise that will never be and become a place where “lakes overflow with the dead”?

In a war, there are no winners. But any paradise, too, has its time. They lose out and become purgatory and then hell. Only a novelist can see that. This surreal and frightening novel of the death and purgatory of a news photographer and an island nation will keep us awake for long, thinking what fate awaits our own country.