Seven easy steps to be a dictator: Two books tell us how

How could Americans vote for Donald Trump? And how on earth did Boris Johnson win the election? Are Modi’s critics anti-national? How could Erdogan force Turkey out of its liberalism? How did Mao become a ruthless dictator? Or Mussolini? Or Hitler?

How could Americans vote for Donald Trump? And how on earth did Boris Johnson win the election? Are Modi’s critics anti-national? How could Erdogan force Turkey out of its liberalism? How did Mao become a ruthless dictator? Or Mussolini? Or Hitler? Or Kim Il-Sung, Stalin, Duvalier, Ceausescu? Two recent books shed light, in different ways, on the “it couldn’t happen here” phenomenon.

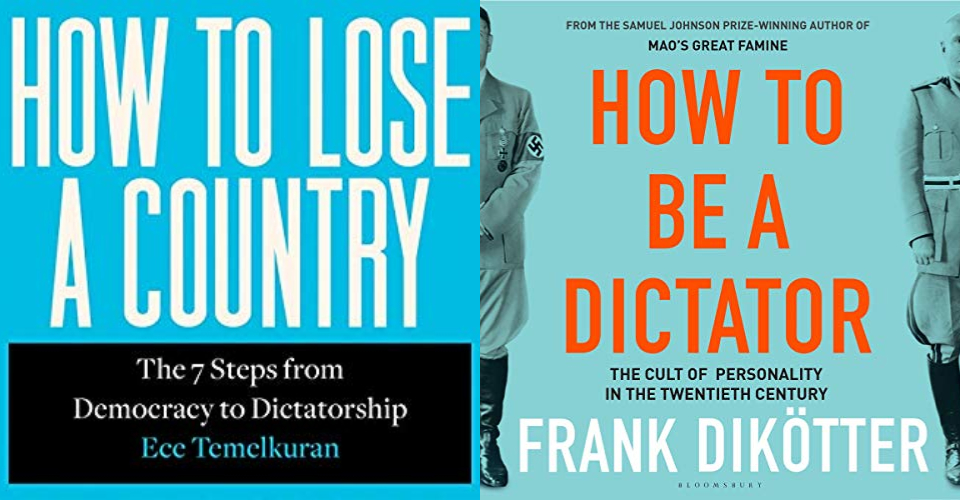

Political commentator Ece Temelkuran in her gripping book, ‘How to Lose a Country — The Seven Steps from Democracy to Dictatorship’ focuses on how Recep Tayyip Erdogan brought about the change by encouraging cronyism and calling his critics terrorists. The award-winning writer and novelist cautions those who say that it cannot happen in their country that they may not recognise the warnings that are already there and it may already be too late.

Having become a dictator, what does a leader do? Encourage sycophancy, crush all legitimate criticism, label detractors as enemies, ceaselessly promote oneself as a hardworking, humble and poor person, and build up a larger-than-life image with the help of fawning journalists, says Prof. Frank Dikotter in his scholarly work, ‘How to Be a Dictator—The Cult of Personality in the Twentieth Century.’ Dikotter chronicles the rise—and inevitable fall—of seven leaders of the 20th century, whose techniques, surely, are being avidly read by power-hungry politicians around the world today.

Related news | 50 shades of ecofeminism: Book profiles global ‘sheroes’ of nature

Last year, Trinamool Congress MP Mahua Moitra shot into the national limelight with a fiery speech in which she highlighted some of the steps to fascism. She was relentlessly trolled. Temelkuran’s trenchant criticism of the Turkish government reducing politics to entertainment has had a greater impact on her life. She now lives abroad, in Zagreb. Leaders, she says, first create a popular movement, promising to restore dignity and self-respect. Trump was the master in this, when he wrote, “I play to people’s fantasies. People want to believe that something is the biggest and the greatest and the most spectacular. I call it truthful hyperbole. It is an innocent form of exaggeration – and a very effective form of promotion.”

Temelkuran’s narrative chronicles public meetings, street protests and interviews, highlighting a choice comment that put in context the outlandish statements of people and how politicians get away with these. She weaves in her own analysis — heavy and academic unlike the racy description of events and meetings — towards the end of each chapter to expose Turkey’s democratic principles, one step at a time.

She writes about political opponents being labelled as outsiders, the enemy and traitors and not fit to stay in the country. While her book is confined to the Turkish landscape, readers around the world will say, “Yes, yes, we have this in our country too.” The parallels are everywhere around us: Language must be debased and labels given for everything, an us-versus-them agitation created and a daily dose of fabrications and falsehoods propagated, using a co-opted media. Arguments are rebutted by attacking the character of the adversary rather than refuting the substance of the argument. The other tactic is to appeal to ignorance by asserting a proposition is true because it has not been refuted or assuming it is true because many people believe it.

Related news | Book comparing Narendra Modi with Shivaji ‘insulting’, ban it: Raut

Political and judicial institutions soon are made subservient to the masters so that the question that reverberates through society is whether we really need these institutions. The leader strengthens the idea that his power and that of his supporters is actually greater than that of democratic institutions.

“If we are not politically active or reactive, then the act of understanding turns into only the expression of emotional responses,” Temelkuran says. While she does not specify what a concerned citizen should do, her book creates awareness about the subtle and not-so-subtle undermining of democracy.

Dikotter’s book is more a collection of short biographies of eight widely known dictators than a unified analysis of their common traits. It is left to the reader to wade through all of them and spot the similarities and differences. Dictators, says Prof. Dikotter have their plate full: they are constantly worried about losing power and have to be wary of the machinations of their aides. They have to constantly prop up the image of a thinker and encourage sycophancy. Our own DK Baruah encapsulated this during the Emergency with his slogan, “India is Indira. Indira is India.” Mussolini, Stalin and Mao may be gone, but we have plenty of narcissistic leaders around.

Related news | In trying times, Kashmiris find catharsis in prayers, books and TV series

What Dikotter and Temelkuran do not talk about is the lasting damage done to the victims of despotism. The Chinese Cultural Revolution left millions dead, with a large population scarred for life. What impelled Mao — like fellow dictators — to become mass murders and face no retribution would be a fascinating subject of study. The dictators thought that they were unshakable, like their statues. “They had captured the souls of their subjects and moulded their thinking,” Dikotter says. “But there was never a spell. There was fear and when it evaporated, the entire edifice collapsed.” Whether it was Mussolini or Mao, Stalin or Hitler, all of them were forgotten the minute they died.

Unlike Temulkaran, Dikotter does not believe in the death of democracy or the end of liberalism. “Dictators with the exception of Kim Jong-un” he writes, “are a long way from instilling the fear their predecessors inflicted on their populations at the height of the twentieth century.” That is a happy thought one can console oneself with amidst all this chaos and gloom.

(G Krishnan has seen plenty of hubris among the many leaders he dealt with during the 40 years he covered politics for national and international publications.)

How To Lose A Country—The Seven Steps From Democracy to Dictatorship, by Ece Temelkuran, 4th Estate, London, 282 pages, Rs. 1,050.

How To Be A Dictator—The Cult Of Personality In The Twentieth Century, by Frank Dikotter, Bloombury Publishing, London, 274 pages, Rs. 550.