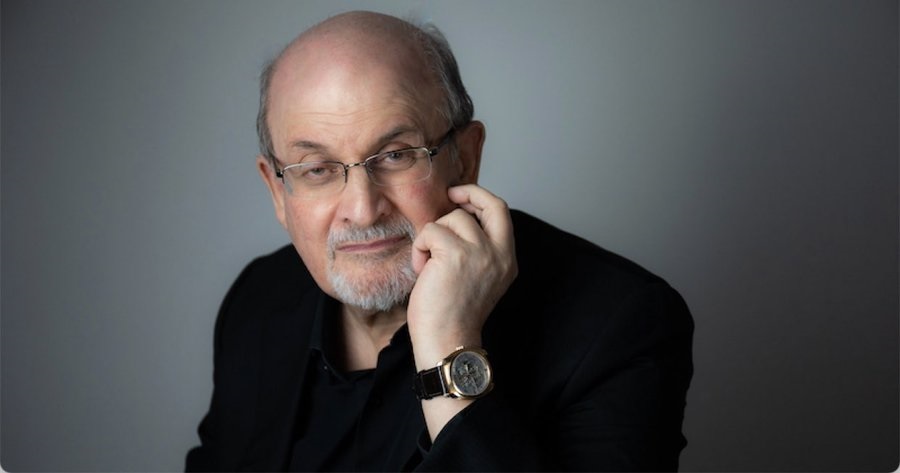

Salman Rushdie emerges as bookies’ favourite for Literature Nobel

Rushdie leads the 2022 race, along with French literary provocateur Michel Houellebecq, according to online betting sites. Will Rushdie make it?

In three days, the Swedish Academy is going to announce the winner of the 2022 Nobel Prize for Literature, putting the global spotlight on one author, and sending the literary world into a tizzy. By zeroing in on one author, most likely someone living in relative obscurity, it will also leave scores of writers around the world — especially those who perennially lead the Literature Nobel race in the prelude to its announcement on October 6 — sanguine, if not sour.

If it doesn’t play safe this year, the Norwegian Nobel Committee’s decision will also trigger a debate, all over again, on its much-talked-about sins of omission and dubious choice.

Salman Rushdie, 75, has emerged as a clear contender for the Nobel Prize this year, according to online betting sites. The bettors on sites like Ladbrokes, Betway, 22Bet, BetOnline, and Paddy Power — they’ve moneylines on literature prizes — have placed large bets in favour of the India-born author and free speech advocate, who was stabbed and seriously injured in August at the Chautauqua Institute in upper New York State.

Also read: Salman Rushdie attack – Why his book The Satanic Verses created such a furore

The attack on the author, who lived in hiding for over a decade — after Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Khomeini issued death edict against him for ‘blaspheming Islam’ in his 1988 novel The Satanic Verses — was followed by a swell of support for Rushdie, with many fans demanding the Nobel Prize for him.

The pole position: Michel Houellebecq and other French writers

The only author ahead of Rushdie in the race, according to the betting sites, is the 66-year-old literary provocateur Michel Houellebecq, touted to be ‘the most widely read living French author in the world’. His eighth novel, Anéantir (Annihilate/Destroy), a 735-pages doorstopper, was published early this year and is perhaps going to be his last; he has said this in some interviews.

A political thriller, Annihilate seeks to do what Houellebecq’s 2015 novel Submission did — feed into right-wing populism. His early novel imagined France as a Muslim state in 2022, stoking fears of the country’s Islamist takeover. His latest envisages 2027 French election amid threats from terrorists.

There are several other French writers who figure among the top favourites of the betting world. French memoirist Annie Ernaux, who was in the race last year too, makes a comeback. Getting Lost, her 1988 diary written during an obsessive affair with a Russian diplomat, was published by Fitzcarraldo Editions a few weeks ago.

Pierre Michon, one of France’s foremost contemporary writers, is also in the reckoning. His first novel, Small Lives (1984), a portrait of eight individuals in his native region of La Creuse, is widely considered to be a masterpiece of contemporary French literature.

Also read: They finally got through to an unsuspecting Rushdie

French writer and playwright Hélène Cixous, who experiments with various writing styles and multiple genres — theater, literary and feminist theory, art criticism, autobiography and poetic fiction — is also among the bookies’ favourite. So is Francophone novelist-theorist Maryse Condé, a writer of multifaceted novels, who like Cixous, questions patriarchal images of literary characters, colonialism, sex and gender.

Between 2008 and 2014, the jurors of the Swedish Academy crowned two French writers — MG Le Clézio (known for his intricately-wrought seductive fiction) in 2008 and Patrick Modiano of the autofiction fame in 2014. In 2022, will they bestow the literary glitter upon yet another French writer? Unlikely, if you ask me. But, then, the literary elite of Sweden is capable of doing anything.

The race and other contenders

Other authors leading the race include Kenyan writer Ngugi Wa Thiong’o, Japan’s Haruki Murakami (an eternal favourite of the bookies), Norway’s Jon Fosse, France’s Annie Ernaux and Antigua-born Jamaica Kincaid. Ngugi, like previous years, figures in the top three tipped to win, but his chances seem slim, considering the Academy picked Tanzania-born Abdulrazak Gurnah last year, and it likes to shuffle between continents. Gurnah was awarded “for his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents.”

The Swedish Academy has a penchant to put the spotlight on little-known authors. After Bob Dylan’s 2016 win, however, it has become clear that it’s not averse to awarding mainstream writers and poets. Joan Didion, who died last year, had figured among the likely names to be considered for the honour. This year, Spain’s Javier Marías and British author Hilary Mantel were tipped to win, but their names were removed from the betting sites after they passed away in September, 11 days apart: Marías on September 11 and Mantel on September 22.

In its long history, the Nobel Prize has been awarded posthumously only twice: to Dag Hammarskjöld (for Peace, 1961) and Erik Axel Karlfeldt (for Literature, 1931). Since 1974, the Statutes of the Nobel Foundation stipulate that a prize cannot be awarded posthumously, unless death has occurred after the announcement of the Nobel Prize.

Also read: How Kalki Krishnamurthy became a cult before ‘Ponniyin Selvan’

Dylan’s win caused heartburn to Roth, who died two years later, and Don DeLillo (85), another frontrunner for many years. In 2020, American poet and essayist Louise Glück won the coveted prize “for her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal.”

Some speculate that a few popular authors who have dominated the buzz around Literature Noble may get lucky this year: they include US novelists Joyce Carol Oates (84) and Thomas Pynchon (85), and Hungary’s Laszlo Krasznahorkai (68), to name just a few. Considering the Academy snubbed American literary magnets like William James Mark Twain, Henry James, Edith Wharton, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, Theodore Dreiser, John Updike, Philip Roth, perhaps it may look to the US to shed its anti-Americanism/Americanophobia it’s often accused of.

The Swedish Academy’s dilemma

‘The Eighteen’ members of the Swedish Academy, who secretively decide on the winner of the 10 million SEK (nearly $1 million) award, stare at a tough choice this year. Since 2022 has seen the shattering of decades-long peace in Europe due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — which has brought the world on the brink of a nuclear disaster — should they consider a writer from Ukraine to underline the popular anti-Kremlin sentiment? Or should they listen to the vociferous demand of a select group of readers and writers around the world to award the Nobel Prize to Rushdie, which will be a shot in the arm for a champion of free speech like Rushdie and a slap in the face of the fundamentalists like Hadi Matar, who stabbed the writer a dozen times in front of a crowd that had gathered for a lecture?

In March, days after Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, the Committee of Literary Studies of Polish Academy of Sciences (CLSPAS) nominated Ukraine’s ‘rockstar poet’, novelist, essayist, and translator Serhiy Zhadan for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Zhadan is credited with having revolutionised Ukrainian poetry with his verses, which are less sentimental and revive the style of 1920s Ukrainian avant-garde writers like Mykhaylo Semenko or Mike Johanssen. Most of his poems draw upon his homeland: the industrial landscapes of East Ukraine. His latest novel, The Orphanage (2021), excavates the human collateral damage wrought by the conflict in eastern Ukraine.

Also read: Archives of pain: The ‘other trilogy’ that Hilary Mantel wrote

“Zhadan is one of the most prominent poets in Ukraine, he’s a remarkable prose writer, whose works are translated into many languages and acknowledged with awards all over the world – we consider him to be deserving of the Nobel Prize. His voice as a poet for many years has been holding a special place in Ukrainians’ hearts. Free Ukraine in many ways speaks and thinks in Zhadan’s words, listens carefully to them. Today the poet is in his Kharkiv. And he is fighting,” reads the statement from CLSPAS on its website.

In 2015, Nobel Prize was awarded to Belarussian author Svetlana Alexievich for her “portrayal of the harshness of life in the Soviet Union.” In her first public response after the announcement, Alexievich had denounced Russia’s intervention in Ukraine as an “invasion”. Alexievich was born in Ukraine, but lived in exile for many years because of her criticism of the Belarussian government. After she returned home in 2011, she kept a low profile, and stayed ‘out of politics.’

Alexievich collected hundreds of interviews from people whose lives were affected by these tumultuous events. Putting them together in works (like In Voices from Chernobyl, 1997) was akin to a “musical composition,” the Academy said.

The Nobel Prize campaigns for Rushdie

After Rushdie, named after the 12th-century Spanish-Arab philosopher Ibn Rushd — known in the Western world as Averroës, he was at the forefront of the rationalist argument against Islamic literalism in his time — was attacked on August 12, scores of critics, writers, editors and academic institutions started drawing the attention of the Nobel Committee to bestow this year’s Nobel Prize on him. They include Margaret Atwood, Ian McEwan, Neil Gaiman, JK Rowling and Stephen King, and many others. Atwood declared, “If we don’t defend free speech, we live in tyranny: Salman Rushdie shows us that.”

Seventy-four-year-old McEwan, whose 18th novel Lessons centres on the fall of the Berlin Wall and the global events penetrating the lives of individuals, told The Guardian recently that the death edict against Rushdie was “a world-historical moment that had immediate personal effects, because we had to learn to think again, to learn the language of free speech.” He added: “It was a very steep learning curve.

The fatwa just preceded a rather wonderful time when democracies were sprouting out across Europe, free speech was on the rise, free thought was on the rise. Everything has changed from 33 years ago. We now live in a time of heavily constricted, shrinking freedom of expression around the world: Russia, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, China, you name it. Plus the self-inflicted free speech matter of the rich west.”

In a somewhat hyperbolic essay in The Atlantic, ‘The Immortal Salman Rushdie,’ Bernard-Henri Lévy termed the attack on Rushdie as an outrage not only against a great and brave author but against truth and beauty themselves, which needed to be met with a “ringing” response. “This act of terror against his body and his books is an absolute act of terror against all the world’s books,” he wrote, underlining that he could not imagine any other writer today who would wish to win it in his stead.

A glorious message

In The Buffalo News, columnist and critic Jeff Simon expressed hope that Rushdie will win the prestigious prize, saying: “A Nobel for Rushdie wouldn’t only be a glorious message from our civilization to all who would decry “the free word”; it would, in effect, be a way of redeeming, in its hour of need, the Nobel Prize for Literature itself… And now just imagine what it might possibly mean this October if they decided, after all, to give the Nobel to [him], who currently lives and works in America but is civilization’s very symbol of how much courage is often required of the written word in this world.”

David Remnick, critic and the editor of New Yorker, was forthright and distinctly earnest in his appeal. “As a literary artist, Rushdie is richly deserving of the Nobel, and the case is only augmented by his role as an uncompromising defender of freedom and a symbol of resiliency. No such gesture could reverse the wave of illiberalism that has engulfed so much of the world. But, after all its bewildering choices, the Swedish Academy has the opportunity, by answering the ugliness of a state-issued death sentence with the dignity of its highest award, to rebuke all the clerics, autocrats, and demagogues—including our own—who would galvanise their followers at the expense of human liberty. Freedom of expression, as Rushdie’s ordeal reminds us, has never come free, but the prize is worth the price,” he wrote in the essay, “It’s Time for Salman Rushdie’s Nobel Prize.”

Remnick, however, was only echoing what Jonathan Russell Clark, literary critic and contributing editor at Literary Hub had written in 2015, five years after Rushdie’s name appeared on an Al-Qaeda hit list. In an essay, ‘Why Salman Rushdie Should Win the Nobel Prize in Literature,’ he made a vigorous plea to the Nobel committee, to award the Nobel to Rushdie — “a secular writer preoccupied with religious storytelling, enticed by the power of narratives to explain, to moralise, to control.”

Also read: The downfall of Indra: How the warrior god of Vedic age was sidelined

“Rushdie is a politically engaged novelist whose books vividly evoke not only his homeland, India, but also London, New York and numerous places in the distant past; he is a knighted Brit, and a major award winner; his writing is full of astounding imagination yet never falls into derivative or (rarely) goofy territory; and when threatened with death with, specifically, assassination, he is a writer who kept writing, who spent more than a decade under police protection, under house arrest, basically unfree, instead of giving in and retracting a word of his book. Nobel committee, what’s good?” Russell Clark asked.

In his concluding lines, Russell Clark wrote that Rushdie should be awarded the Nobel Prize not just because of the fatwa, but “because his novels are extraordinary contributions to the world of letters, and his imagination remains rich and alive to the depth and complexity of being human.” He wrote: “We need more writers like Rushdie, more books like his—books that refuse simple answers and provoke strong responses. We need art that challenges, dissents, that won’t stand down. We need artists who are courageous, open to the world, who want to better it. In other words, we need more Satanic verses.”

Too little, too late

It took the Swedish Academy 27 long years to respond to the Iranian death warrant against Rushdie. It paid little heed even when two of its members, Kerstin Ekman and Lars Gyllensten, refused to participate in the Academy’s work over its refusal to make an appeal to the Swedish cabinet in support for Rushdie. It was Canada that became the first country in the world to pass a unanimous, all-party resolution, demanding the withdrawal of the death edict. The efforts of PEN Canada and its then president Louise Dennys were instrumental.

When, in 2016, the Academy finally took a stance, it was too little, too late. “The fact that the death sentence has been passed as punishment for a work of literature also implies a serious violation of free speech,” the academy said in a statement in 2016. As the author is in the process of recovering from the grievous injuries after the attack, will the Academy make up for its nearly-three-decades-long silence on the Rushdie affairs?