Archives of pain: The ‘other trilogy’ that Hilary Mantel wrote

“Sometimes you come to a thing you can’t write,” wrote Dame Hilary Mantel (1952-2022) towards the end of her loosely autobiographical collection of short stories, Learning to Talk (2003), which was meant as a companion piece to her memoir Giving Up the Ghost, published in the same year. Her untimely death — she passed away on Thursday after suffering a stroke — is one of those things.

The headlines announcing the demise of the British author were strewn with phrases like ‘Wolf Hall’, ‘historical fiction’, ‘the trilogy’, and ‘bestselling author’. Wolf Hall (2009), Bring up the Bodies (2012) and The Mirror and the Light (2020) constitute her extremely well-written and stupendously successful trilogy. Two of these won the Booker, making Mantel the first British author, and the first woman author, to win the prize twice. A mini-series produced by the BBC and plays produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company made the trilogy a part of our collective imagination.

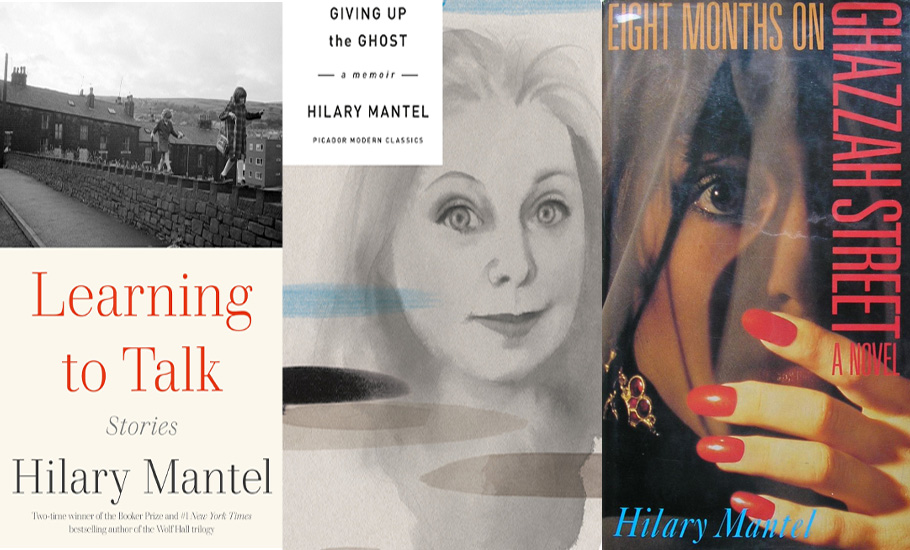

However, to pay tribute to Mantel, I would like to write from a more personal imagination, of what I call the ‘Other Trilogy’. To speak about all her books or stories is beyond the scope of any one article. To merely mention them would be to do what Mantel kept away from in her historical fiction — the superficial listing of events and names and dates. Just as Mantel chose the complexly intelligent Thomas Cromwell rather than the grander royals to tell her story of a particular time in history, I choose from her impressive body of work these comparatively less grand, very complex books: Eight Months on Ghazzah Street (1988), Giving Up the Ghost, and Learning to Talk. Three books that speak most of her personal life — a life fraught with untreated physical pain and the emotional hurt that the lack of understanding, and treatment and comfort caused.

Eight Months on Ghazzah Street

Frances, a British woman, has moved to an Islamic country with her husband Andrew, an architect. Mantel had lived in Saudi Arabia with her husband, a geologist. But the actual plot may not be lifted from her life; it is not autobiographical. But it is definitely what Mantel will, in 2022, call ‘autoscopic’.

“If you could get outside your own body and see a double of yourself, but that double had a slightly different story,” Mantel said in an interview to CBS in July 2022. Frances has a life different from the one led by the 30-year-old Mantel. Frances hears sounds from the upstairs flat. She sees a gun-wielding, disguised figure leave; also, a body is carried out in a packing case. Mantel herself was living in an “in an ageing prefabricated house where rats bounced and scurried in the roof.” Did the sounds made by rodents turn into the comings and goings of a murderer? Mantel made notes on what would become the life of Frances in the novel that she would finally write in 1986 in England, after leaving sufficient time and distance between her and the actual location of the novel. A location which, it is obvious, that the author has experienced first-hand.

Also read: The Kwan Kung Temple: Inside Mumbai’s only Chinese shrine

The feeling of isolation that comes over Frances, the protagonist, whose freedom of movement is curtailed, the conversations with local women that range from very intelligent and freely expressed political opinions to the fun moments of sharing the recipe for Jeddah gin. The astute observations of Mantel, the writer, about the way men interact with women is expressed in the form of Frances seeing a “destructive infantile greed” in the glance of a hotel clerk who has, until this moment of looking at her with this ‘greed,’ not even acknowledged her presence, choosing to talk only with her husband.

Eight Months on Ghazzah Street reveals sharp journalistic ability, good story-telling and a nuanced understanding of the loves of others. Her second novel is an indication of the excellence to come. Mantel had once joked, while speaking of the distance writers need to keep from their characters, that it was required because after all we know their ending, but they do not. While writing this book, this young writer in her early thirties did not know the greatness her writing would achieve. We, the readers, however, do.

Giving up the Ghost

“I am not writing to solicit any special sympathy. People survive much worse and never put pain to paper. I am writing to take charge of the story of my childhood, of my childlessness; and in order to locate myself, if not within a body, then, in a narrow space between one letter and the next, between the lines, where the stories are,” wrote Mantel in Giving up the Ghost, a book about coming to terms when you cannot overcome. A book about learning to live with pain. For the pain never left her.

It’s a book about struggling with weight that does not end with before/after pictures or descriptions of a ‘slimming success’. The body stays the same. But the book ends with this woman, who everyone saw as fat and ugly, becoming a successful writer. A book that is vital not only for those of us that can identify with the trauma of being misdiagnosed, ignored and humiliated by medical professionals, but for everyone, who at some point or other, has felt vulnerable because of their body.

Also read: Where the stones speak to us: How Hampi conquered my mind and memory

There is, especially if you identify with the kind of body the book is talking about, the possibility of being angry at her, about one thing. I was. Of all the bad things that happened to her because of the misdiagnosis, Mantel is saddest about the fat, the weight she put on because of the medication. Why is being fat the worst thing, one may ask. One may also see as ridicule Mantel’s descriptions of a nurse named Della: “…so wide, you couldn’t see around her” or “a bison”. Also, patients at a liver- scan USG clinic: “Jaundiced, bloated people holding their abdomens on their forearms like debutantes at a ball”. Anger.

And then one saw a video of an interview she did, the difficulty she had in movement. The pain was visible on her face even as she joked about how her historical fiction was successful because it carried the time-tested formula of “the royals and sex and violence.” A shocking joke, to take our attention away from her pain. So that is what the descriptions were then. She was not ridiculing others. She was laughing at herself, at her pain. At being so close to death. For although the book says it is about leaving behind the ‘ghosts’ of the oppressive figures of childhood, Giving up the Ghost is also the Christian phrase for dying.

Also read: Encounter with vodka à la Rooskie: When two Russians went berserk

Learning to Talk

“…we continued to live in one of those houses where there was never any money, and doors were slammed hard. One day the glass did spring out of the kitchen cupboard, at the mere touch of my fingertips. At once, I threw up my hands to protect my eyes. Between my fingers, for some years, you could see the delicate scars like the ghosts of lace gloves, that the cuts left behind,” Mantel wrote in the story, ‘Curved is the Line of Beauty.’ In the collection, she tried to show us how a child looks at life, the language in which she describes life, and that sad memories are also beautiful memories. The six stories make us laugh even as we are moved by the bewilderment that the child protagonists seem to feel about the world.

These, then, were the three books where Hilary Mantel wrote about her life. Although on repeated reading, one might get an understanding of pain, and how it affects thought, even in her historical fiction. Of journeys fraught by pain, journeys from humble origins. Thomas Cromwell, the son of a blacksmith, rises to become powerful: the “second man in England.”

Mantel came from a working-class home and rose to become a successful writer. In one of her last interviews, she said, “I have more ideas than years to execute them in…”. Unfortunately for all of us, she was right.

Dr Manasee Palshikar aka Nadi Palshikar, a novelist, briefly taught at the FTII. Her novel, Sutak, was received warmly, and appreciated for its treatment of gender and caste.