‘Novelist as a Vocation’ review: How Murakami animates the surreal world of his fiction

Does the novel matter in the world we inhabit today? It’s a question that fiction writers around the world have been preoccupied with for a while. Delivering the annual Goldsmiths Prize Lecture on ‘Why the Novel Matters?’, Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgård elaborated on the future of the novel.

The event was live-streamed from the Queen Elizabeth Hall at the Southbank Centre in London; I was there in person. As Knausgård spoke, a spectral digital replication of him was simultaneously projected onto the large screen behind him. It left many wondering whether the advent of information technologies and digital platforms have offset the vocation of the novelist onto a path of obsolescence.

For the technology versus text conundrum, Knausgård has an excellent premise: In today’s world, the novelist is quintessentially a stupid person, someone who has voluntarily chosen to remain on the margins of a shared and productive global time. In other words, there is such a high premium on efficiency and productivity, specifically the ways in which we invest our time and labour, that only a stupid person would dare to risk the slowness required in writing novels.

On the importance of novels

In such times, the novel matters greatly because it is one of the few activities that offers an escape route from the tyranny of goal and profit-oriented behaviour that is foisted upon us. Engaging in the slow pace of a novel, with no insurance of an outcome, is an act of rebellion against productivity and the short-attention spans generated by algorithms of social media platforms, but even more importantly it gives us the permission to stay deeply embedded in the materiality of the present.

Also read: Inside the violent, visceral world of Cormac McCarthy, one of America’s greatest writers

This could explain literature’s enduring love for the ‘idiot’ or the madman, a character that represents the untenable goodness and generosity of the human spirit — whether it be Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Myshkin in The Idiot or Tarjei Vesaas’ Norwegian classic The Birds (1957) based on the meaningful inner-life of a mentally disabled subject, Mattis, who has intensely symbolic attachment to the flight of the woodcocks over his house.

Now, there happens to be another literary giant of our time, Haruki Murakami, whose most recent book the Novelist as a Vocation embodies Knausgård’s proposition of the novel as one of the few solitary activities in contemporary society. In the sense that the essays compiled in this book allow us to witness Murakami implementing the theory of the slow-time of the novel in his daily work routines and the quotidian activities of his everyday life.

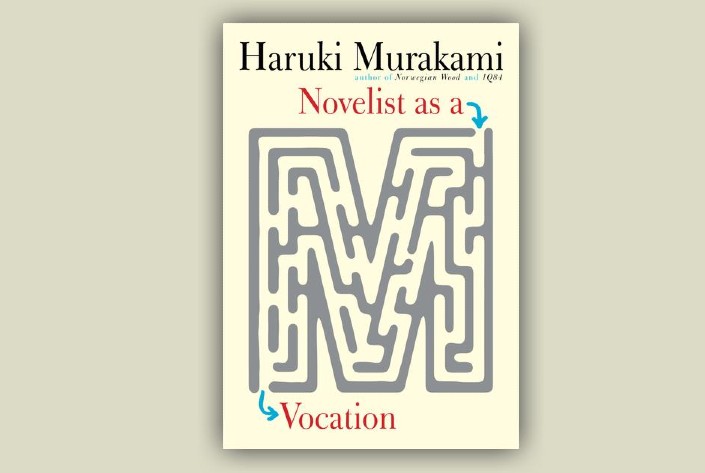

Novelist as a Vocation comprises 11 essays that were originally dispatched in 2015 as monthly contributions for a reputed literary magazine in Japan; they have now been translated by Philip Gabriel and Ted Goossen, and published by Harvill Secker (Penguin Random House).

In each of the essays, Murakami presents thoughts on the methodology and practice of fiction writing. On one level, it is an opportunity to glimpse into Murakami’s inner psychic and creative processes and how they animate the surreal world of his novels. While also delving into his lifelong journey as a writer, beginning with the early publications, the harsh criticism of his best-selling novels in Japan and his rather belated entry into the American publishing industry.

In the first essay, ‘Are Novelists Broad-minded?’, Murakami offers an anecdote to illustrate the practical philosophy of the novelist’s vocation. He writes: Two men go to see Mount Fuji for the first time; the intelligent man stands at the foot of the slope, he efficiently sizes up the mountain from different vantage points by using various metrics. He quickly announces that he fully understands the beauty of the Fuji-San and returns home.

The other man, who is most likely an archetype of the novelist is stupid and so he cannot cognitively grasp the mountain through abstract theoretical concepts, he has to climb the mountain all the way to the summit, every day for years till he finally ‘grasps the essence at a less conscious level’ and even then there is a risk that he keeps climbing Mount Fuji over and over without ever having figured it out at all, or worse he realises, the more he climbs the less he understands.

Also read: Manohar Devadoss: With his eyes and a pen, he brought Madurai to life

To me, Murakami’s story about the daily practice of grasping the beauty of Mount Fuji is an exemplary application of Knausgård’s concept of the ‘stupid’ novelist, who inhabits a slower temporal register and, therefore, carries the risk of becoming anachronistic in today’s world. It is Murakami’s genius that appends to the vocation of the novelist, a profound gentleness towards the physical suffering that is inflicted by cognition, teaching us that we can never cede the work despite the lack of outcome, that we must somehow learn to continue the task of attending to the text with patience and humility.

On White Blood Cells

In the last essay, ‘Going Abroad: A New Frontier, Murakami writes that in his early 40’s, the mass popularity of his novels soared in Japan; Norwegian Wood alone sold over two million copies. Yet, on a personal front, he found himself unable to enjoy success as a bestselling novelist due to the storm of vindictive campaigns led by the Japanese literary establishment.

The polarised debate among literary critics stressed the disjunction between Murakami’s work and the history of Japanese literature, arguing that his novels appeared apolitical but to an extent functioned by reproducing the colonial and imperialist narratives of modern American literature within a Japanese context.

Murakami recounts an incident where a well-known critic of modern Japanese literature publicly stated that he was in ‘big trouble’ if he thought he could pass off such effortless prose, lacking in any style whatsoever, as literature. It was implied that if Murakami was the best contemporary novelist in Japan, then even those with no aptitude for writing could become writers.

This maelstrom of cultural criticism in Japan forced him into exile as he decided to leave the country and restart his career in America. Murakami credits much of his global success to his relationship with the editors at The New Yorker magazine, who exclusively published his translated short stories, thereby enabling him to recognise the value of good translators, literary agents and loyal readers outside Japan.

By Haruki Murakami, Penguin Random House

In hindsight, the appearance of Murakami novels and its phenomenal success had no precedents in the existing canon of Japanese literary traditions. Murakami compares his critics to the ‘white blood cells’ of an organism, who believe that their function is to protect the authenticity of Japanese culture from invaders, thereby evicting him from the country like a ‘deadly virus’. The severe backlash by these ‘gate-keepers’ of culture was premised on the accusation that his work was unworthy of being deigned literature, let alone being lauded as a literary work of high calibre.

The Gatekeepers of Culture

Interestingly, Murakami also brings up the defence of ‘white blood cells’ to reflect on the innate hospitality of professional fiction writers. As he explains, when a fiction writer changes courses midway to move into a highly specialised social or scientific academic field, they usually find themselves attacked by self-appointed gatekeepers, who act like ‘white blood cells’ intent on purging the discipline of unwanted invaders. In fact, the more specialised or niche a discipline is the more virulent the attack becomes on those perceived to be infiltrating the field as outsiders.

Also read: How Pinocchio, the long-nosed puppet boy, has journeyed across time

Contrarily, such attacks are unheard of when the non-fiction writer decides to switch track midway and create a work of fiction. The communal hospitality of the novelist stands unabated in all circumstances; they continue to extend their welcome by keeping the doors of fiction wide open for one and all. Novelists are rarely competitive or threatened by the presence of newcomers (particularly from other non-fiction disciplines), because being an accomplished fiction writer is not so much about the defence of a disciplinary frontiers or guarding cultural authenticity. Instead, it is a matter of endurance, much like running a long-distance marathon.

Murakami’s exposition on white blood cells and fiction writing happened to distinctly remind me of an event that occurred in India and left an imprint on my mind as a young woman growing up in the 2000s.This was when the novelist Arundhati Roy published her book of political essays after winning the Booker Prize for her novel The God of Small Things. A certain renowned elite male academic spearheaded a public diatribe against Roy because the novelist had crossed the threshold of fiction writing to enter the sanctified disciplinary field of the social and political sciences. The paternalistic configurations of the cultural gatekeepers in India provides yet another dimension to the polemic between fiction and non-fiction writers. Roy was reprimanded, (rather, horribly mansplained) asking to curb her hysteric flight of fictious imagination, which was not only politically untruthful but bordered on self-indulgent and self-contradictory.

Looking back at this incident, which remains etched in our collective memory, it is only in hindsight that one can ruminate on the lack of a feminist political consciousness in those years, which gave ballast to the entitlements of certain elite male thinkers, writers and intellectuals in India. Even though patriarchal dogmatism in the cultural and literary scene has not receded to the extent one would like, we must be thankful and to an extent even cruelly optimistic, if possible, about the galvanisation of feminist movements, including the so-called ‘cancel culture’ that has made it a notch more difficult to launch polemics against feminist thinkers in the public cultural sphere.

But, more importantly, a sustained effort to curtail the free-license of upper-caste elite intellectuals in India to speak on behalf of everyone and everything, without having any real lived or embodied experience of sexual, sectarian or caste-based subjugation themselves.

To sum it up, there are not many accomplished novelists who have written so extensively about their own daily writing practice. Previously, Murakami explored an overlapping interest in long-distance running and novel-writing in the book What I Talk About When I Talk About Running (2005). Some excerpts from this book have been republished in Novelist as a Vocation, as at one point he asserts that — ‘Most of what I learned about writing fiction I learned from running every day.’

One is led to wonder why Murakami felt the need to publish these lengthy justifications for writing fiction, where he painstakingly outlines his daily work routines and the disciplinary measure of writing no less than 1000 words, sitting for 6 hours at his desk every day, through a gesture of regulating his productive output much like a factory worker clocking the hours on a punch card. Perhaps the force of criticism against his unconventional novels in Japan that had a part to play in these lengthy essays reflecting on the process of fiction writing.

The Japanese literary critic Norihiro Kato has written eloquently about the onset of a long-term ‘fatigue’ of a literary giant like Haruki Murakami, due to being eluded by the Nobel Prize Committee for over two decades. He was initially nominated in 2005, when Kafka on the Shore made it to the New York Times bestseller list and continues to be nominated every year. Yet, regardless of the Prize, the opinions of critics and the sales figures of his books, Murakami remains unfazed in the exploration of human relations and stories about the Japanese culture that captivate readers all around the world. As an experienced and well-trained marathon runner, he is independent and committed to his work above all else.