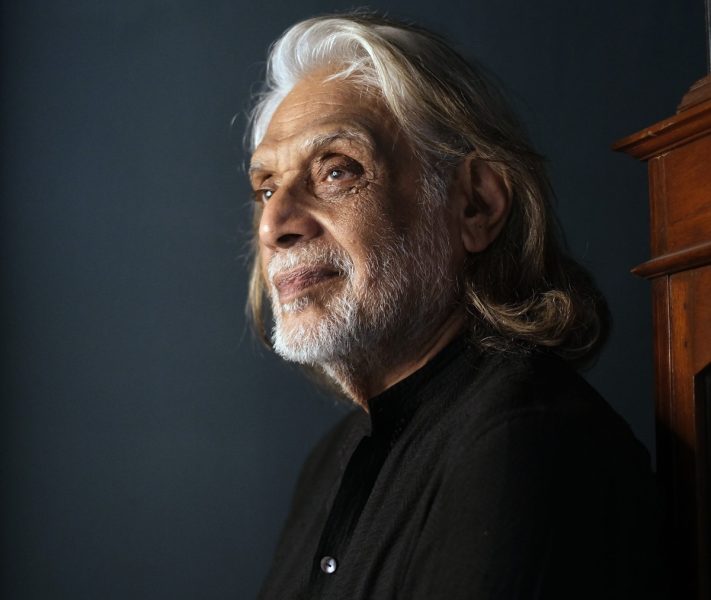

Muzaffar Ali: ‘Art in India needs a breath of fresh air and freedom’

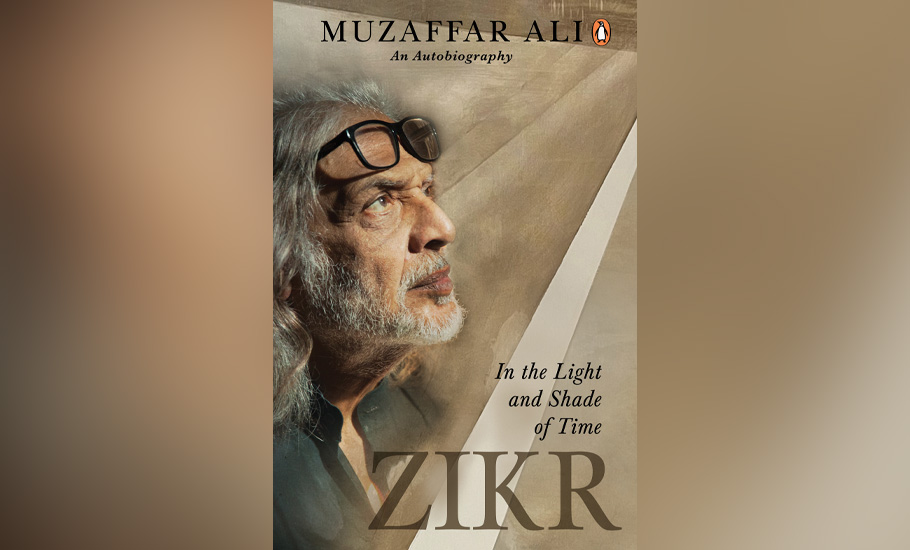

Art knows no boundaries, and Muzaffar Ali’s extensive work as a filmmaker, fashion designer, painter, music composer and social worker bears testimony to this maxim. In his recent autobiography, Zikr: In the Light and Shade of Time (Penguin Random House India), Ali looks back at his journey, the influence of his father, Raja Syed Sajid Husain Ali, on him, and their shared penchant for luxury cars.

Ali, 78, began his professional career by joining the advertising agency Clarion McCann in Calcutta. He later joined Air India in Bombay and spearheaded many significant brand campaigns. The 1978 film Gaman marked his foray into Hindi cinema as a filmmaker, and Umrao Jaan (1981) catapulted him to the upper echelons. However, after making several films, TV serials and documentaries in the 80s, Ali faced a setback with his feature film, Zooni, on the life of Kashmiri poet Habba Khatoon. Due to the 1989 insurgency in Kashmir, Ali and his crew had to leave the valley, and since then, his cherished project has yet to be able to see the light of day.

In 1990, Ali and his architect wife Meera established ‘House of Kotwara’, an international fashion house, with the mission to revive the traditional craft of the Awadh region and provide rural employment through their foundation, Dwar Pe Rozi Society (Employment at Doorstep). The same year, he plunged into the world of Sufism and hasn’t looked back since. He heads the New Delhi-based Rumi Foundation and instituted the Annual World Sufi Music Festival, Jahan-e-Khusrau, in 2001. After a two-year hiatus, the festival travelled to Jaipur this year.

In this in-depth interview to The Federal, Ali talks about revisiting his personal memory, his formative years, creating employment opportunities for artisans in Kotwara and Lucknow, the synergy of cultures in India, what drove him to the Sufi poetry and music of Rumi and Amir Khusrau, the decay of Urdu in India, the virtues of multiculturalism, and more.

Excerpts from the interview:

The initial part of Zikr transports the reader to your formative years: childhood in Kotwara, summer holidays in Nainital and the exemplary life of your father. You recount those times with such fascination.

It’s like going back to early childhood when everything had its own kind of wonder. I look back at the lessons imparted by my father, his values and sense of humour, his sense of history and humanism, and how all of this pans out in my life later. I recount a lot of exciting, amusing moments. At the same time, I’m also looking back at life now. That is the interesting dimension. I also reflect on how setups were created for poetry, music, culture and cinema.

The book then moves to your college life at Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), where you graduated in science. AMU played a significant role in shaping you, especially its famed poetry culture. But despite your immense love for poetry, you’ve refrained from writing your own poetry.

AMU was a very exciting time in my life. The remarkable thing that emerged from there was the sense of poetry and romance, which may not be the case in most universities and institutions. It was a melting pot of poetry, and that became like a vocabulary or leitmotif in my work later. One of the milestones in my career was when Faiz Ahmad Faiz penned a beautiful note in appreciation of my debut feature film, Gaman. Why haven’t I attempted writing poetry? One of my closest friends in AMU, Asghar Wajahat, had cautioned me, “If you can get good poetry to hear, don’t attempt to write yourself.” I have lived by his word.

Also read: How Martin Scorsese’s films record modern American cinema’s savage beauty

You’ve been responsible for generating employment for many local artisans in and around Kotwara and Lucknow. Many of them have worked on your films and are associated with your couture brand, House of Kotwara. What is the current situation in that region?

Some things have been steadily happening, and there are other temporary projects based on the work that takes me there. I’m trying to create a place where people can have a lovely time. Then, I have excellent craftsmen there who do work in wood, embroidery and tailoring, etc. That is something that we want to do. It gives them sustenance, makes our presence there relevant and gives them employment at the doorstep, which was also the thrust of Gaman. One is trying to realise these things as an artist.

You’ve previously mentioned that you weren’t very pleased with Satyajit Ray’s portrayal of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah in his film Shatranj Ke Khilari (1977). In Zikr, you talk about the Nawab with great reverence, terming him as an icon of syncretism.

It wasn’t really Ray’s portrayal of Wajid Ali Shah but Premchand’s non-holistic depiction in his book that I have a bone to pick with. I think Wajid Ali Shah has to be looked upon not as a feudal metaphor. One has to see him as a cultural icon who integrated syncretic culture in Awadh. Ray’s motivation was not to touch on that aspect in his film. And it was also beyond Premchand’s vision of Wajid Ali Shah. If I were to make a film on him, I would take on a lot of other shades, which I’ve done in all my works related to Wajid Ali Shah. I’ve made a 13-part television serial Jaan-e-Alam (1986), in which I played him. I’ve also done 13-14 editions of a festival called the Wajid Ali Shah Festival. He was removed unceremoniously and exiled to Calcutta, which left a lot of angst and bitterness in the people. And later, that was probably one of the sparks for the Rebellion of 1857 or the First War of Independence.

Wajid Ali Shah was not just a patron, he was also an artist. Ray has touched upon his art, but he’s touched upon it in a kind of debauched way. I wouldn’t like to play with his image because he’s far too relevant in today’s time and age to be fooled with.

Penguin Random House

There’s a passage in the book where you’ve highlighted the humanism of Emperor Akbar, who told his officials: “Read Rumi. He will make you a better human. If you are human, this nation is human.” Your presentation of Muslim rulers as syncretic is significant as it runs contrary to the distorted narrative of our time.

Now it’s being realised worldwide how important being syncretic and multicultural is for the economy. Even if you go to places like the UAE, they are fiercely multicultural. Obviously, the reason is that it’s very good for the economy, business, tourism and everything else. So, now we also have to realise that. In contrast, we are heading the other way.

Considering the growing divisive climate, what can be done to counter it culturally? In the days of Doordarshan, serials like Shyam Benegal’s Bharat Ek Khoj (1988) and Gulzar’s Mirza Ghalib (1988) depicted the subcontinent’s culture of inclusivity. With the OTT boom now, such shows portraying our composite tradition could help dispel ignorance.

I wouldn’t like to say it, but OTT platforms are certainly avoiding touching such subjects, fearing repercussions. But time will tell, and commercial concerns will only decide what is good for the economy. As far as art is concerned, I think art definitely needs a breath of fresh air and freedom.

It isn’t easy to dig up much of your work. Where can one hope to watch Jaan-e-Alam and your unreleased film Zooni?

I have a few tapes, but there’s no streaming platform where one can watch them. A few things, like all the craft films I’ve made, can be found on our YouTube channel, Muzaffar Ali — House of Kotwara. I did a series of films on Urdu poets, which are available on Doordarshan under Zubaan-e-Ishq. Then there are things I’ve done for the Ministry of External Affairs, which are probably there on their website. Anyway, my interest in my work is marginal. It’s not a commercial compulsion for people to promote my work. The time may come when people might like to know a little more.

Sufism has been the most fascinating part of your life. In the book, you write with so much love and passion about Rumi and Amir Khusrau. So much of our art draws inspiration from them and other Sufi mystics.

As far as Sufism is concerned, India is in a vantage position with regard to content and creativity. It is a confluence of many influences and cultures. And one culture has inspired the other culture. You don’t find this kind of inspiration or synergy in other places. You’ll find a lot of Sufi poetry inspired by Lord Krishna. In that sense, India is at a vantage position, culturally. It has been known for its composite culture. Some people may negate it, but at the same time, the people who are seeking inspiration and truth cherish it.

Also read: How Taylor Swift, the pop sensation, has become an unstoppable force

Kashmir used to be a very strong pocket of our syncretic tradition, which got hijacked because of insurgency. But art has survived there: Khusrau, Rumi, and Sufiyana Kalam can still be found in their verses, music and compositions. That’s why I could forge a stronger connection when I returned to Delhi after the debacle of shooting Zooni in Kashmir. Delhi as a city depends on one’s perception. It is a place of saints that inspires people to look at life differently. That’s what drove me to Sufi poetry and music. And since then, I haven’t looked back, as there is so much to it that one cannot stop getting inspired.

What does the near future look like for you as an artist?

The future could be many-fold. One could be looking at young futures and more music and performing arts. One could also be looking at cinema, but cinema is, unfortunately, a terrain which is limited by the demands of visibility. It has to go through the cumbersome channel of distribution and so on. And then people are heavily dependent on the star system. So, then, this whole new approach to cinema gets distorted. There’s a setback there early on as it is dependent on funds. I prefer to do things where I can move forward without any funds, like painting. I’ve been painting a lot, and that is something which comes more organically and naturally without any pressure. As for the expensive art form of cinema, there may be a time for it again with a different renaissance.

Raqs-e-Inquilab (2019), a documentary, looks at Kashmir through the lens of artists, including painter Masood Hussain. Conflict naturally seeps into their work and becomes their way of expressing dissent. Have you ever felt inclined to take your work into that space?

While I cherish and appreciate such stuff, I don’t think I’m driven that way. I’m more into my own way of expressing and perceiving things. Currently, I’m busy taking Jahan-e-Khusrau into a different kind of realm. I want to take it abroad and make it global and more youthful. In India, we are limited by artists due to border restrictions, and subcontinent art includes Pakistanis and Bangladeshis as well.

What is your take on the decay of Urdu in our country? One of my favourite films is Ismail Merchant’s Muhafiz (In Custody, 1993), an elegy on the waning Urdu culture. Many believe Urdu will eventually die a slow death in India or is that an overtly cynical view?

Urdu is a very organic language and a language of love. That’s why I call it Zubaan-e-Ishq. People cannot be drawn away from it as it is compulsively attractive. Although the avenues for learning it are limited, and post-Partition it has been projected as a non-Indian language, the vocabulary of Urdu is so rich that many people cherish it as is evident in the popularity of old Bollywood film songs. The best thing is that the youth is getting drawn to it because of movements like ‘Rekhta’ and Urdu WhatsApp groups. So, fortunately, it cannot be killed despite many mediums of Urdu being destroyed. We need to foster a culture of learning. There are so many interesting things people can learn: music, Urdu. For me, learning Farsi is essential. If one gets into a learning mode, it brings out a special kind of sensitivity in a human being. I find beauty in a lot of Indian languages.

One good thing about the internet is that it doesn’t let good things die. For example, many YouTube channels are now devoted to Urdu poetry, with viewership only increasing daily.

This is a miracle of our time. Despite many elements wanting to keep people away from it, there will be individuals drawn to Urdu, and collectively would be a considerable number. I foresee a similar thing happening to film content. Ultimately, the makers will create stuff that the viewers want. So, the signals will reach the money bags. But if you take a larger footprint of art, then one can do wonders. For instance, my whole foray into Rumi is very personal and intimate, but at the same time, I feel it has the potential to engulf the entire world. There’s so much art that emerges from Rumi. I find his poetry full of imagery, metaphors and abstraction that lends itself to painting, music, dance and moving images.

You had plans to make an international movie on Rumi? Why didn’t it take off?

I’ve written several scripts on Rumi, but making a film is such an expensive business that it’s yet to take off. At one point, Qatar Foundation had shown interest in funding the project, but I had to face the reality of casting stars to make it commercially viable. And considering the legal and other market hassles, working with a star doesn’t allow dreamers like me to realise their dream.