How Charles Sobhraj, an escape artist, turned into a cold-blooded murderer

Notorious conman Charles Sobhraj, 78, walked free from Golghar, the high-security zone in the Kathmandu Central Jail, where he has been languishing since 2003, after Nepal’s Supreme Court, taking into consideration his ailing condition, ordered his release on Wednesday (December 21). The 19-year jail term is the longest the serial killer has served in his eventful life as a fraudster with frequent run-ins with the law.

“The police may wish to keep me in prison throughout my life. But they can never defeat my will to be free,” the beret-clad Svengali and escape artist had declared once. “I can escape at will. I can rob at will. I can live exactly as I want,” he had added. The dawn of his new-found freedom makes his words, filled with the steadfast resolve with which he executed his diabolic missions as a murderer, eerily prescient.

Before his near-two-decade incarceration at Golghar, Charles had spent almost a decade at Tihar Jail after his arrest from Delhi’s Vikram Hotel in 1976. A decade latter, on March 16, 1986, he broke out of Tihar, India’s most guarded jail, only to be arrested in Mumbai after a month-long manhunt.

The story of the flesh-and-blood ‘bikini killer,’ who eventually came to be known as the serpent for his ability to slither — at will — out of the grasp of the police, is the stuff of legend, steeped in brazenness, audacity and unscrupulousness, but also in worldliness, intelligence and charm.

Also read: Serial killer Charles Sobhraj to be released from Nepal jail after 19 years

The tales of Charles’ villainous past are also laced with his uncanny knack for hoodwinking people into believing anything and holding young and unsuspecting hippie women under the spell of his hypnotic gaze. He drugged, robbed and killed scores of tourists, but in most of these cases he first trapped the women with his wily charm, luring them with the promise of elusive windfall.

The childhood years

Hatchand Bhaonani Gurumukh Charles Sobhraj’s mother, Noi aka Tran Loang Phun, was a waif who grew up in Saigon, “the Paris of the Orient”, as the Vietnam war raged on. His father, an Indian textile merchant, Sobhraj Hatchand Bavani, was born in Mumbai.

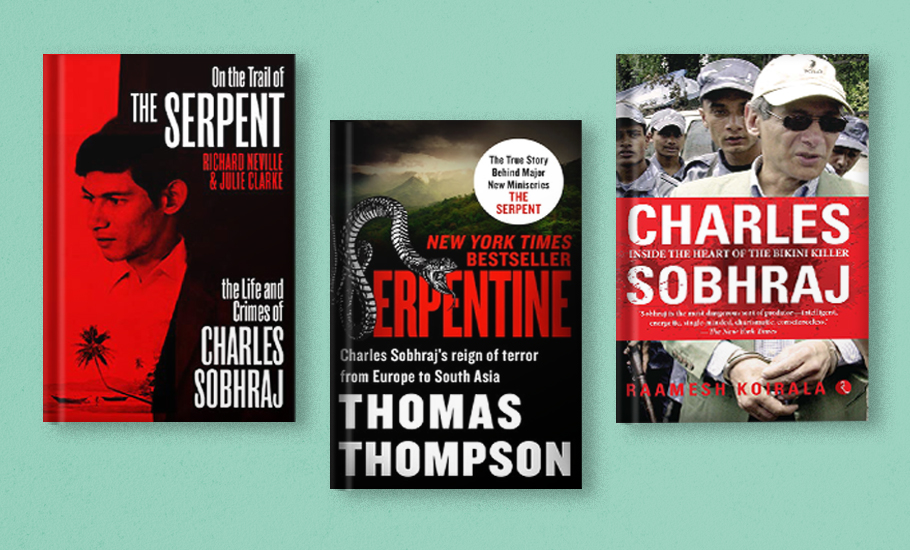

When Charles was three and Noi was pregnant again, Hatchand returned from a visit to his home in Poona, and announced that he had married an Indian girl, write Richard Neville and Julie Clarke write in On the Trail of the Serpent: The Life and Crimes of Charles Sobhraj: Richard Neville; Julie Clarke (Penguin Random House). Enraged, Noi stormed out of the apartment, with Charles under her arm.

Soon, she happened to meet Jacques Roussel, a shy and sensitive adjutant-sergeant from Bordeaux, who fell in love with Noi and agreed to accept Charles as his son. They were married in September 1948, after the birth of Noi’s second child by Hotchand. She was named Nicole, after Roussel’s mother, and was formally adopted at the wedding ceremony.

As a young boy, Sobhraj was christened Charles after the hero of the times, President de Gaulle. Separated from Hatchand and Saigon, he never came to terms with the loss of his homeland, and his father, always craving to go back to the life he had left behind to live with his stepfather in France.

Battle-weary after Vietnam, Roussel was sent on an administrative posting in the sleepy French protectorate of Senegal in West Africa. In 1957, when Charles was 13, he sailed from Marseilles with the Roussel family to the capital city, Dakar, where he was enrolled in the Orientation College. But he did his best to attend it as little as possible, and often forged his father’s signature on explanatory absence notes.

Charles started to slow his destructive energy from a young age. At 15, he studied in the class with the twelve-year-olds, struggling with a new language in a new land. His report card was a sheaf of shame. Soon, Roussel decided to discontinue the farce of his stepson’s education and found him a job as an apprentice mechanic in the garage of a friend. A few days later, he was sent home. He had reversed the wires on the electrical transformer and almost burnt down the building housing the garage.

The problem with Charles, who had been shunted back and forth between parents and continents, was that the young man simply did not know who he was nor where he belonged, a priest had told Hatchand. “He possessed no roots, no security, no feeling of membership in either a family or a national culture. The priest suggested that Hatchand arrange citizenship for his truant son,” writes Thomas Thompson in Serpentine.

However, it was not so easy. When Hatchand once tried, he spent frustrating days at the Indian Consulate in Saigon, trying to obtain a passport and citizen papers. The Indian government would not bestow citizenship unless Charles spent a minimum of one year on its soil, during which he had to become fluent in an Indian language.

An incorrigible criminal

In 1963, Charles was caught for a charge of burglary and received his first custodial sentence at the Poissy Jail near Paris. He was only 19, but had established himself an incorrigible criminal.

“His term in the Parisian prison was perhaps the last chance he had to pause—and reverse—the infernal storm taking over his soul. But he did not take it. Instead, he learnt to manipulate, to use his charming, seductive personality to get people to do his bidding. He managed to convince the jail authorities to bring him books on literature and foreign languages,” writes Raamesh Koirala, a cardiac surgeon who operated on Charles’ heart in 2017, in Charles Sobhraj: Inside the Heart of the Bikini Killer (Rupa Publications).

His situation was precarious. When he came out of jail, he would be kicked out of France because he didn’t have a passport. “It is better to be a citizen of the world than of Rome,” he told Alain Benard, his benevolent lawyer in France, to whom he portrayed himself as a wounded young man. He also told him about his stoicism and his art of living above the external circumstances of life. The prison priest described him as “exceptionally bright”, and a rebel, who lived in a world of his own, refusing to come to terms with reality.

Also read: Ramdev’s Divya Pharmacy among 16 Indian firms blacklisted in Nepal

In jail, Charles also befriended Felix d’Escogne, a prison volunteer and a wealthy Parisian. The two decided to stay together when Charles was on parole. While in Poissy, Charles got an intimate exposure to the criminal underworld of France. Felix’s friendship took him very close to Parisian high society.

“This was not the society Charles hailed from, but he fitted right in; his knowledge of literature and foreign languages wonderfully complemented his handsome personality. With feline grace and cunning, he clawed his way into this world, marrying crime and riches. He had to belong to this world now, whatever it took. To maintain the standards he wanted to portray to the world, he was in constant need of money. No wonder then that his favourite crimes—robbing tourists and breaking into houses—continued with increasing momentum,” Koirala writes. It was around this time that Charles met his first wife, Chantal Compagnon, a wealthy Parisian girl from a conservative French family.

Charles’ statelessness had contributed to his feeling of dislocation. And since he detested the idea of being a wallflower, and loved a life of luxury, he turned to crime with a vengeance. Moral compunction didn’t exist in his scheme of things. And he never regretted what he did.

Charles knew all along that his path was not easy and he had to keep upgrading himself in order to evade the arms of law. He kept cultivating his image as a suave, sophisticated man that granted him easy access everywhere. “It seemed that Charles sought not only self-improvement, but an intellectual armoury — he wanted the weapons, conventional and otherwise, to cut through the jungle outside, to carve his path to the top. Socially, Charles was on the bottom rung, without wealth, nationality or education, and jail had added a five-year handicap,” write Neville and Clarke.

“But he had inherited one gift, the gift of charisma, of power over people. Charles had decided to build on this and to learn all he could about clues to the human character; the better, he thought, one day to mould them to his will. Palmistry, handwriting analysis and characterology would help him penetrate other minds and would offer shortcuts in social relations,” Neville and Clarke write. As a stowaway, trying to flee from France in order to meet his father, he would have the gumption to freely eat and drink in first-class, without inviting a hint of suspicion.

Charles had multiple fake passports, all with photographs uncannily resembling him. If they didn’t, he was cunning enough to throw on a disguise. At immigration checkpoints, they would take one look at his sophisticated demeanour, quickly inspect the passport, and tell him to ‘please proceed.’ Living at his rented apartment in Bangkok, he would move freely through Asia, leaving a trail of crime behind: young hippie women in bikini gagged or drugged and, sometimes, with slit throats.

At 32, Charles became the darling of the murky social circles in Bangkok. The fact that he had fashioned a new identity as a gem dealer started attracting more hippies to his den. To keep up with the growing business, he befriended two people who became his partners—the Canadian, Marie-Andrée Leclerc, and the Indian, Ajay Choudhury. But, soon, he soon grew weary and greedy, and removed them from his path to become the sole architect of his empire.

A new life

After Charles was arrested by the Bombay Police on April 6, 1986, he was taken back to Delhi and thrown into Tihar again. This time, he was handcuffed and fettered in isolation and was not allowed to mix with other inmates. A 10-year sentence for jailbreak was added to the charges against him: just as he had calculated.

When the Indian government decided to deport the 53-year-old Charles to France on April 8, 1997, he finally had his identity. With a travel document in his name, he was not a stateless man anymore, but a French national with an authentic passport. The photograph in the passport was his.

A year after he was arrested in 2003, the Kathmandu District Court found Charles Sobhraj guilty of the 1975 murder of Connie Jo Bronzich, an American tourist, in 1975. The charges of passport forgery and illegal travel were also upheld. Charles was sentenced to life imprisonment.

With his zest for life intact, Charles married his Indian-Nepali interpreter, Nihita Biswas, the daughter of his lawyer — 44 years his junior — inside the prison in 2010. She told the media that his gaze and his eyes were mesmerizing and that his French charm had done everything; in 2017, she donated blood to save Charles when he had to undergo an open heart operation.

‘What makes a man a murderer?’ a news channel once asked Charles. ‘Feeling,’ he said, simply and nonchalantly. ‘Either they have too much feeling and cannot control themselves, or they have no feeling. It is always one of the two.’ Sobhraj, the perpetrator of a string of murders across Asia in the 1970s, belongs to the latter category.