Dadaji’s Paintbrush: A children’s book gently explores themes of death, grief, loss and healing

Rashmi Sirdeshpande, a lawyer-turned-storyteller, was born and raised in the United Kingdom, but spent some of her childhood years in Goa with her grandparents. After she moved back to the UK to live with her parents, they made sure that the family travelled to Goa every year.

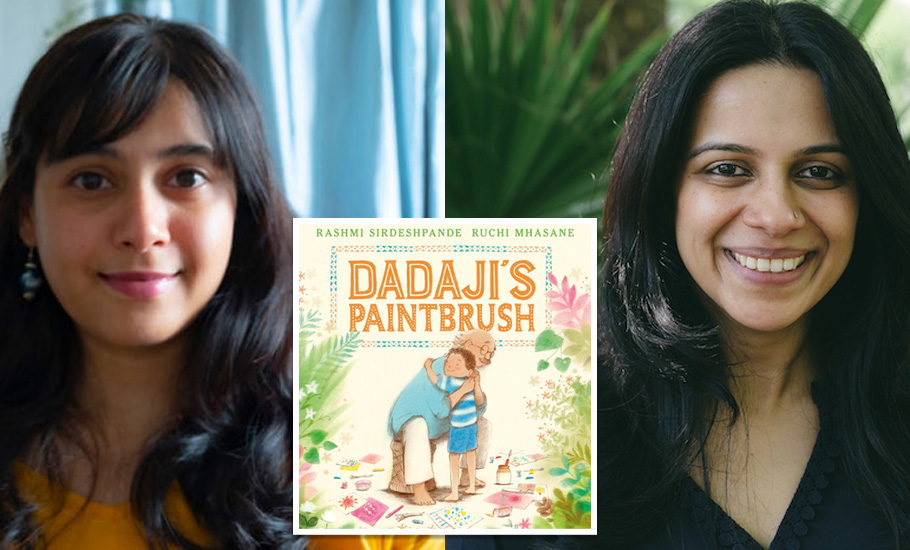

Growing up as a “British Indian child”, she rarely saw people like herself in the books that she was exposed to. She is now committed to writing books that children from diverse backgrounds can relate to. Her book Dadaji’s Paintbrush, published by Andersen Press, was shortlisted for the Jhalak Prize 2023 in the Children’s and Young Adult Literature category.

It is built around the special bond between a boy and his grandfather. They spend a lot of time together, creating works of art with brushes, reeds, flowers, betel leaves and coconut shells. They make paper boats, grow fruits, and gaze at stars as they fall asleep on the terrace.

The weight of loss

This blissful picture is disrupted when the grandfather dies, and this book explores how the grandson comes to terms with this unbearable loss. At first, the boy cannot get himself to use the favourite paintbrush left behind by his deceased grandfather. With the passage of time, he discovers how many lives Dadaji had touched with his art. He finds a way to honour his grandfather’s legacy, and begins engaging with other children in the village who like to paint.

Also read: Truth/Untruth review: Mahasweta Devi’s exploration of love and lust in Calcutta of 1980s

Rashmi has dedicated the book to her paternal grandfather Laxmikant Desai. She says, “When I visited him in India, I remember how tightly he’d hug me when it was time to go. I have a line like that in the book where the boy’s grandfather holds him so tight his bones hurt! That’s the truest line I’ve ever written.” The book also draws inspiration from Rashmi’s father who grew up in Goa, loves the arts, and finds numerous ways to give back to his community.

It seems odd that Rashmi has set the book in what she calls “a tiny village in India,” but avoided mentioning any specificities in terms of state or region. Was it because, as an author who lives in the UK, she was writing primarily for an international readership? She says, “I wanted to show rural India but without specifics to keep that feeling of universality and the whimsical feel of the story. The people in it are never named and that is for the same reason.”

Rashmi got down to writing this book many years after her grandfather passed away but telling this story was not a sudden decision. She has been nursing the desire to write “a book capturing my love and honouring my grandfather” for a while. “It feels so special to know that his name is bound up with this book and that the memory of our bond has been transformed into a story that has touched and will touch so many lives,” she says. Working on this book reminded her that people live on in one’s heart, and that “love never ceases to be”.

The grandparent-grandchild bond

What kind of reception has this book received from readers in India, the UK and elsewhere? Rashmi has heard from “children who marvel at the sight of mangoes and paints and rich, leafy settings to grown-ups who remember their own fathers and grandfathers”.

Also read: Maulana Azad: A Life review: The enduring legacy of a freedom fighter and nation-builder

Readers have been moved by the grandparent-grandchild bond depicted in the book. Those who belong to the South Asian diaspora are not used to seeing a “Dadaji” in picture books published in the UK, so Rashmi has been getting several messages thanking her for creating this book. “I cannot read them or respond to them without my eyes filling up with tears. I am grateful to have played a part in creating something that has touched readers so deeply,” she remarks.

The impact of this book owes greatly to Ruchi Mhasane’s illustrations. An MA in Children’s Book Illustration from the Cambridge School of Art in the UK, she lives in India. Working with the story that Rashmi wrote was a memorable experience for her because the Goan setting shares many similarities — the coastline, the monsoon, and abundance of mangoes, bananas and coconuts — with the Konkan region that Ruchi knows intimately.

Ruchi has dedicated Dadaji’s Paintbrush to both sets of her grandparents — Aaji-Abba and Aaji-Anna. She has stronger memories of her grandmothers rather than grandfathers. She says, “Every summer my father’s mum would make a year’s supply of papads and other dried snacks, which she would lay on the terrace to sun-dry. There were rice kurdayis and nagli (or nachani or ragi) papads, and she made everything from scratch. I loved the taste of the savoury ragi dough, so as she rolled papads out, she would give me little lumps to eat.”

Delving into big feelings

Her maternal grandmother taught her knitting, amongst many other things. Ruchi says, “Aaji taught it by teaching me the logic of it, rather than a formula to make a sock or scarf. Explaining the underlying logic is the deepest way to understand even the simplest of things, and it never leaves you.”

Ruchi gets nostalgic when asked to share more about what they their presence meant to her. “Whatever any of my grandparents did, I remember them doing it with care, joy and sincerity. I remember in them a love of labour and a simplicity of life, something that will always stay with me and what I would like to continue in their memory.”

Also read: Courting Hindustan review: A glimpse into the lives of courtesans across ages

In a 2022 blog post titled “An Early Look at Dadaji’s Paintbrush”, which is published on the website of Andersen Press, Ruchi throws some light on the thought process guiding her choice of medium, material and technique. She notes, “I have used mainly colour pencils and pastels on paper, but the images are built up over a number of papers using a lightbox, which are put together digitally; this allowed me to play with the strength of the colours, since some pages are quite busy, especially the ones with the paintings made by the characters.”

Parents often find it challenging to answer children’s questions about death and the afterlife, or they believe that children ought to be protected from grim realities like loss and suffering. How can a book like Dadaji’s Paintbrush help them ease into these conversations?

Rashmi thinks that books can “provide a safe space for readers to explore big feelings and leave children with a feeling of hope.” With her book, she wanted to comfort them, and reassure them that the people we love will always stay with us through our memories and actions.