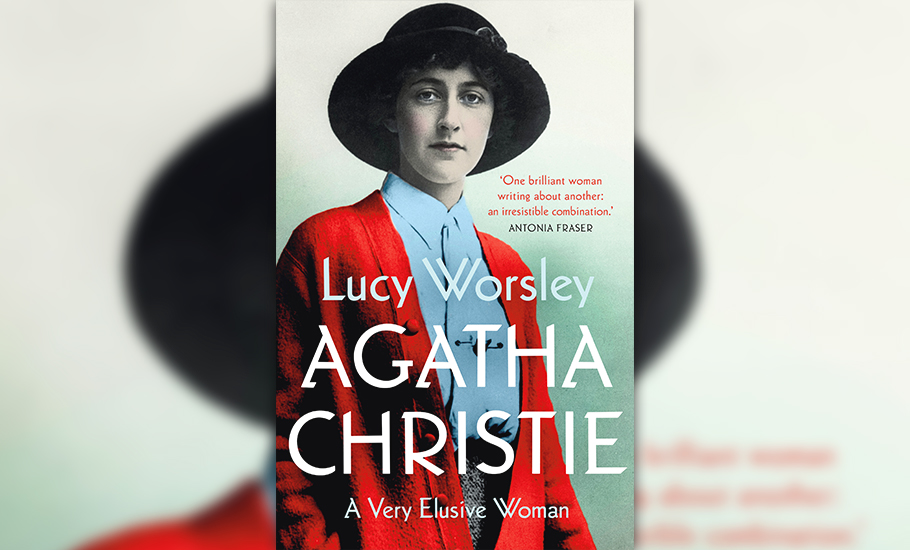

Book review: Why Agatha Christie spent her life pretending to be ordinary

Agatha Christie, the undisputed queen of whodunits, had a clutch of mysteries of her own. A new biography of the ‘Duchess of Death’ — Agatha Christie: A Very Elusive Woman by celebrated British literary and cultural historian Lucy Worsley— untangles the complex and storied life of the author by putting in perspective events from her life. They include her infamous 11-day disappearance in 1926, after which the creator of characters like the egg-headed, moustache-twirling Belgian detective Hercule Poirot and consultant detective Miss Marple, retreated from public view. The book, extensively researched and bristling with a deep empathy (despite Christie’s views on race and class in her books that will be considered problematic today) for the subject, unravels her mystique and clears away misperceptions around her life as well as her works of fiction.

One of the great writers of the twentieth century, Christie (1890-1976) lived through two world wars, the decline of the British Empire, and nearly a century of violent social change. She has chronicled all this in her 66 detective novels and 14 short story collections, as well as the world’s longest-running play, The Mousetrap. Her books have sold over a billion copies — in English as well as in translation. Christie is the best-selling author after Shakespeare and the Bible, according to a cliché that has been in circulation for long. But she had her share of hardships (after she lost her father at an early age) and suffering, both in personal and literary spheres.

At the heart of Worsley’s biography is a quest to explore how Christie, who had made waves with her very first novel, spent her entire life pretending to be ordinary. Worsley writes that Christie was ambivalent about her fame and extraordinary professional success. The author who’s estimated to have sold two billion copies always liked to call herself a ‘housewife.’ In her passport, she gave her profession not as ‘author’ but simply as ‘married woman’. When Christie arrived at the party celebrating the 2,239th performance of The Mousetrap, the hotel staff didn’t recognise her and refused to let her in. Instead of announcing that she was the star guest at the celebration, Christie shyly slunk away. Why did Christie craft such a persona for herself, presenting to the world a version of herself greatly at odds with her real self? The biography, which runs into over 500 pages, answers this question. Her books are Christie’s enduring legacy, but Worsley tells us that she was not just a novelist whose success has made us see her as an institution, but also “a breaker of new ground.”

Also read: ‘The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida’ review: When paradise turns to purgatory

The Man-Magnet

The villa named Ashfield in Torquay (Devon) was central to Christie’s life. It was there that she was born and grew up, along with her siblings — brother Monty, who disliked any kind of work and, later in life, became addicted to morphia; and Madge, her pretty and witty actress sister, who had ‘a great deal of sexual magnetism’ and who later married James Watts, the heir to Abney Hall. Incidentally, Christie’s first novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920), was the result of a dare from Madge, who challenged her to write a story. In her youth, Madge wrote stories and plays quite ‘effortlessly.’

Christie loved life in motion. “Your travel life,” she wrote, “has the essence of a dream… you are yourself, but a different self.” As a modern young woman, Christie loved swimming, and fast cars; she was also intrigued by the new science of psychology. She also loved men, with equal fervour and frenzy. By twenty-two, Christie had received nine proposals. ‘We have only known each other ten days,’ she told one suitor, ‘it’s really an awfully silly thing to go and propose to a girl like that.” In 1912, even as she was into her ninth ‘desultory courtship’ with an army officer named Reggie Lucy, she met the 10th man after she walked into the ballroom. He seemed to hold out the promise of “a marriage of equals, of shared values, and of adventure.”

That man was Colonel Archibald Christie, a British businessman and military officer, who became the first husband of the mystery writer; the two married in 1914 and divorced in 1928 apparently over his infidelity; he later married Nancy Neele, the former secretary of British Empire’s Major Belcher. Christie, Worsley informs us, had begun to see that “within an ending may lie a new beginning”. Christie wrote in her diary: “I am tired of the past/ that clings around my feet/ I am tired of the past that will not let life be sweet./ I would cut it away with a knife and say/ Let me be myself – reborn – today.” In 1930, Christie remarried; an archaeologist named Max Mallowan was the man; adventures with him provided the settings for many of Christie’s books, like Death on the Nile (1937), in which Poirot draws a parallel between detection and archaeology: both aim to excavate the truth.

‘Christie trick’: Her greatest achievement

Christie published her sixth novel, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, in 1926. According to Worsley, it was her greatest achievement yet. “It is not only one of her very best books – it’s one of the greatest detective novels of all time. She invested a lot of care in this book,” Worsley tells us. In the novel, Poirot moves to an English village to spend a quiet retirement, growing vegetable marrows. Instead, he’s called upon to solve a fiendishly complex case. The story is told by an unreliable narrator.

Also read: Annie Ernaux is an ethnographer of memories, a master of autofiction

In The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Dr Sheppard does not tell the reader everything he knows; his skilfully placed silences create a false impression. Worsley terms this omission of tiny, but key facts by someone the reader has come to trust as the ‘Christie trick’ that she would play again and again, bending the conventions of the crime fiction of the period. This perfectly constructed piece of deception, however, added to Agatha’s growing reputation for guile, the biographer writes, and came to be counted against her when she disappeared in 1926.

Christie created a fictional world that had much in common with her real life although she painted it in dark colours. Unlike her role model, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Christie gave the lives of women centrestage. In her 1916 novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, she wrote about a world she knew well, with her characters inspired by family, friends and servants, living in a country house. Many courtships unfold simultaneously, and the ‘upstairs’ characters live off income they don’t quite earn. Even the novel’s murder speaks directly to her own family situation. The victim, Mrs Inglethorp, is a matriarch: a powerful, older woman, along the lines of Auntie-Grannie, or even Clara (Christie’s mother), to whom the book was dedicated; Miss Marple is modelled on the life of Auntie- Grannie, with whom Christie spent a few years as a child.

“It’s not just Alfred and Evelyn in Styles, who are pretending to be something they aren’t. Practically all the characters are keeping up a pretence of one kind or another. Agatha was very familiar with this: after all, she was pretending to be married, pretending the work in the hospital wasn’t awful. So many of her killers likewise try to pass for normal in the world of her books,” Worsley writes.

Her own detective

If she bent conventions of crime fiction with keeping women at the centre of the narrative, Christie also crafted her own detective in Poirot, first introduced in The Mysterious Affair at Styles. With a detective with ridiculous moustache, she broke new ground: Poirot is a detective whom it is “dangerously easy” to underestimate. Christie chose him to be of Belgian nationality since she was inspired by the growing number of refugees who’d started to appear in wartime Torquay. By deciding to make Poirot a foreigner, and a refugee, she created “the perfect detective for an age when everyone was growing surfeited with soldiers and action heroes”.

Since he’s so physically unimpressive, we do not expect Poirot to steal the show. He cannot rely upon brawn to solve problems, but his brains instead. ‘There is no need of physical effort,’ he explains, ‘one needs only – to think. Christie would also show Poirot working in a different way to Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes. In Sherlock’s first fictional appearance, A Study in Scarlet (1887), the great detective lies down flat on the floor to gather up ‘a little pile of grey dust’. It was cigar ash, and from his encyclopaedic knowledge of the different kinds of ash made by different kinds of cigar, he could deduce which brand the murderer had been smoking. But Christie parodies the scene in an early appearance of Poirot’s. Worsley writes: “Unlike Holmes, he utterly refuses to lie down to examine a crime scene — the grass is damp! — and completely fails to ‘scoop up cigarette ash when I do not know one kind from the other’. Poirot will not stoop to ‘gather clues’. He needs only his little grey cells. Brainy, physically awkward, and unexpectedly brilliant, Poirot is liked by many. But by readers who are themselves a bit geeky, though, he’s utterly beloved. Like Sherlock Holmes, he’s an oddball and a loner. Yet unlike Holmes, with his ennui and his drug addiction, Poirot’s completely happy.”

Her own story

Her 1926 ‘mental illness’ nearly broke Agatha Christie. But ultimately, Worsely writes, it also proved to be the making of her. The year had a huge impact on her and left its traces all through her work. It also made her the great woman she became.

After the drama of 1926, Agatha’s daily life may also read as “small beer, full of everyday doings and happenings.” By pretending to be ordinary, Christie sidestepped a world that tried to define her. “She was easy to overlook, as is the case with nearly any woman past middle age. But Agatha deliberately played upon the fact that she seemed so ordinary. It was a public image she carefully crafted to conceal her real self,” Worsley underlines. Christie had once written: “You can’t write your fate. Your fate comes to you. But you can do what you like with the characters you create.” This may have been a statement of her life’s philosophy: Christie had truly been a woman who’d written her own story.