Basu Chatterji and Middle-of-the-Road Cinema review: Rain, Bombay and lives of common people

Recently, an elderly couple recreated a popular scene, channeling the magic of Amitabh Bachchan and Moushumi Chatterjee in the song Rimjhim Gire Saawan. This song evokes nostalgia for Mumbai’s rain and romantic walks, which have the power to rekindle lost memories that a city carries.

The scene was originally shot for the film Manzil (1979), directed by Basu Chatterji. Known as a middle-of-the-road filmmaker, Chatterji shared his unique perspective on cities, life, and rain in his movies, becoming synonymous with Bombay’s rain and the city itself.

In his latest book, Basu Chatterji and Middle-of-the-Road Cinema (Penguin Books), writer Anirudha Bhattacharjee explores the career of a filmmaker, who carved his own path by telling stories of ordinary people. Through movies like Chhoti Si Baat (1976), Piya Ka Ghar (1972), Rajnigandha (1974), and Chitchor (1976), Chatterji created his niche by making movies focused on relatable characters from the middle class.

The Nayi Kahani movement and Sara Akash

Born in Ajmer (Rajasthan) in 1927, Chatterji’s family later shifted to Mathura when he was four. He started his career as a librarian and then became a political cartoonist for the weekly magazine Current and later for the Hindi division of Blitz. Bhattacharjee skillfully captures how Chatterji’s love for cinema led him towards filmmaking.

The book primarily focuses on his filmmaking journey and process, making it a delightful read. Although it lacks a bit in bringing Chatterji as a person to the forefront, this actually keeps the narrative focused and tight.

Chatterji’s rise in the film industry coincided with a movement in Hindi literature called Nayi Kahani, which emerged during the 1950s. This storytelling movement followed the post-Premchand period of story writing and was led by new writers like Mohan Rakesh, Kamleshwar, Mannu Bhandari and Rajendra Yadav. These writers began exploring themes related to middle-class families, erosion of values, insecurity, melancholy, loneliness, and anxiety.

Also read: Jubilee review: A lavish ode to Hindi cinema, an epic tale of ambition and stardom

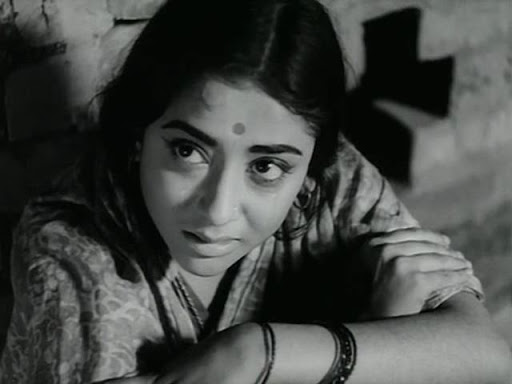

One novella by one of the key figures of the Nayi Kahani Movement, Rajendra Yadav, titled Sara Akash, became the starting point of Chatterji’s career. Sara Akash (1969) focuses on the challenges faced by a young college student forced into an untimely marriage. The film delves into the protagonist’s idealism and nationalism, shattered by the suffocating pressure to conform. AK Hangal portrays the father, while Rakesh Pandey plays the angsty hero Samar. The talented cast includes Madhu Chakravarty, Tarla Mehta, Mani Kaul, and Jalal Agha.

Basu Chatterji considered Sara Akash to be his finest work, as stated by himself in a 2013 interview to Rajya Sabha TV. Sai Paranjpye, too, underlines in the foreword to Bhattacharjee’s book. Following the release of Sara Akash, Basu made it a point to visit the Yadav family whenever he was in Delhi. The writer couple, Rajendra Yadav and Mannu Bhandari, served as a source of inspiration for some of Basu’s significant cinematic creations. One such film was Rajnigandha, featuring Amol Palekar, Vidya Sinha, and Dinesh Thakur.

Mannu Bhandari’s unique writing style, distinct from her husband’s, contributed to the seamless storytelling, perfect fit for cinematic adaptation. Bhandari’s short story, Yahi Sach Hai, is about the internal conflict of a woman, who is in love with two men. Deepa, the lead character, is emotional, intellectual and values economic independence — quite rare for the time to feature such a strong woman character in the films.

The influence of Western cinema

Chatterji saw Bombay quite differently from popular notions of that time, “Bombay was back in the centre of things in the 1970s coinciding with the birth of the Angry young Man…..Chatterji’s Bombay was not about descent of the young man into crime and turning super-rich,” writes Bhattacharjee. His Bombay was journey of people trying to make their life better, and embracing the city as their own.

Also read: In Anubhav Sinha’s films, the cry for social justice, yearning for real change

In Piya Ka Ghar, there is a dialogue by Mrs. Sharma “28-29 Saal ho gaye is ghar me, ab yahi apna ghar hai. Gaon ko bhul hi gyi” (It’s been 28-29 years in this house, now this is our home. I’ve completely forgotten the village). This dialogue, Bhattacharjee says, brings Chatterji’s “skill of saying a lot with few words.”

Chatterji was a very busy filmmaker; he would always be on the lookout for good stories. His hunger, and success with his unique films, earned him popularity among actors, who would wish to work with him. This included Rajesh Khanna who, in the post-stardom phase, did a movie called Chakravyuha (2016), which remains an aberration for Chatterji, known for middle cinema. But someone who knows Chatterji closely can easily reckon the rationale. He was inspired by a lot of western cinema, which made him adapt some of its films.

Chakravyuha, starring Rajesh Khanna and Neetu Singh, was inspired by Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps (1935). This awkward adaptation didn’t work as it had no dramatic appeal. Another adaptation, which has both been admired and criticised, was Ek Ruka Hua Faisla (1986), based on American courtroom drama film 12 Angry Men.

A fine craftsman

Chatterji was a fine craftsman, but he was not a perfectionist and his movies would have a lot of bloopers. In the shooting of Swami (1977), a diesel engine train arrives, while it was set in 1920s’ Bengal — but Chatterji would make it up with his stories, and dialogues. He was a smart strategist, and he would often finish movie shooting within a month.

One common Bollywoodi-ish characteristic he had was that he preferred the positive ending to his stories. “He told his tale with dollops of humour and great humanity. He saw life sunny side up and for him, the glass was always half full, never half empty,” writes Paranjpye in the foreword.

Also read: How ‘Chandralekha,’ a 1948 Tamil film, paved the way for big-budget Indian films

This attitude of his made him adopt only the first part of Sara Akash. And when he made a popular TV serial Rajani (1993-1994), about the eponymous lead, who is fed up with government laxity, the initial episode was written by Mannu Bhandari. She was not happy with the treatment of her writing, and she fought with him.

Not just that, Bhandari also questioned him for the ending of the film Swami, which was based on Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s story; Bhandari wrote the dialogues for the film. The story revolves around the dilemma of a young and educated girl named Mini, who is married off against her wishes to a wheat trader, Ghanshyam, while she was in love with a Zamidar’s son, Vikram. Chatterji digressed the story by showing Mini falling at Ghanshyam’s feet.

All said and done, Basu Chatterji was one of the tallest figures of the Indian film Industry. Bhattacharjee skillfully weaves together Chatterji’s films and journey, introducing key figures such as cinematographer KK Mahajan, who captured challenging scenarios like rain, as well as music director Salil Chowdhury and lyricist Yogesh, upon whom Chatterji relied. Despite the multitude of characters involved, Bhattacharjee adeptly narrates Chatterji’s story, doing justice to its complexity and depth.