Bahuguna’s Chipko brought conservation, women to the fore

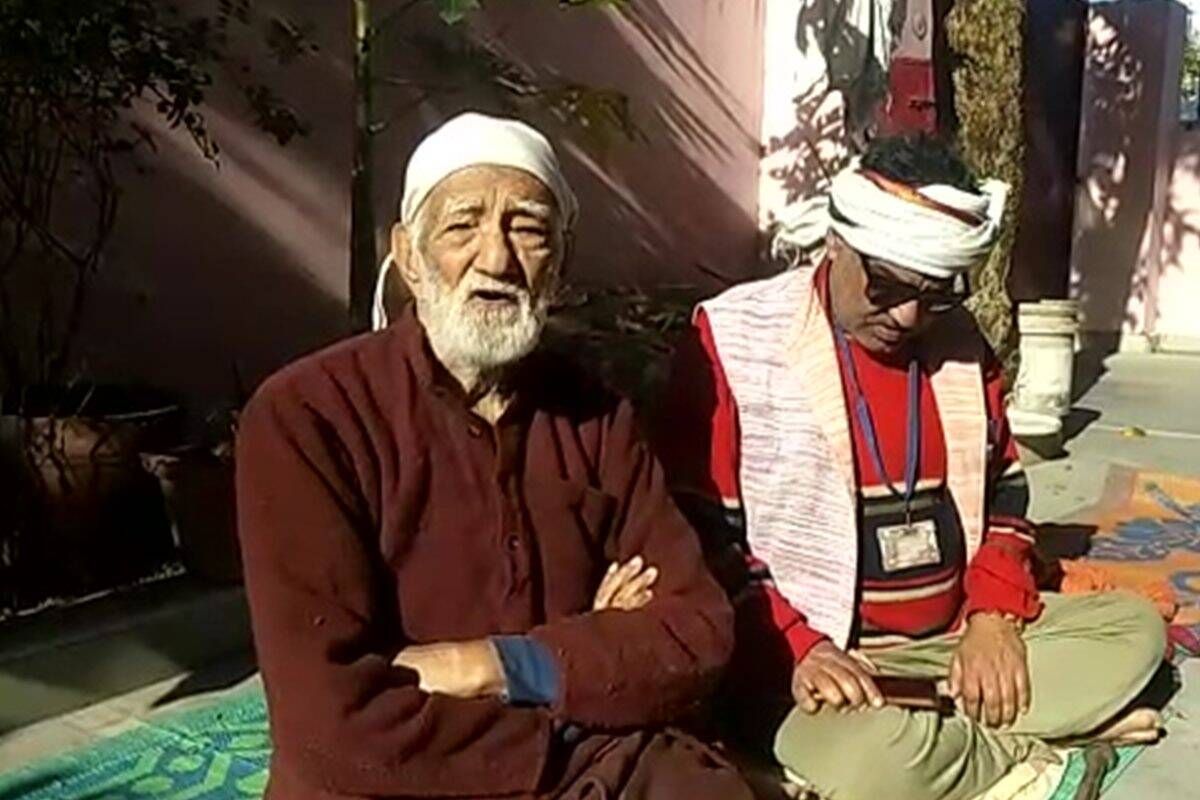

India lost a stalwart – legendary environmentalist Sundarlal Bahuguna – in its COVID battle last month. Bahuguna was credited with the famous Chipko movement of the late 70s and early 80s across the Himalayan range, especially the Uttarakhand region.

India lost a stalwart – legendary environmentalist Sundarlal Bahuguna – in its COVID battle last month. Bahuguna was credited with the famous Chipko movement of the late 70s and early 80s across the Himalayan range, especially the Uttarakhand region.

Bahuguna was among the first few in India to take up issues that have today become critical and brought environment and conservation into the public discourse. In the last 40 years, he has been a voice of nature and of millions depending on it. Such was his charisma that a single meeting of his with the then Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, is believed to have led to a 15-year ban on cutting trees across the region.

What is the big deal though about what he did and why is there a need today to celebrate the work of this one individual? Why is the word ‘Chipko’ momentously importance today, more than anything else? In the worlds of Twitter and the rest of social media and the Greta Thunbergs, Licypriya Kangujams and the Disha Ravis, what Bahuguna achieved seems too little and too localised. Yet, it should be remembered that he pioneered the larger good above the self, the sacrifice above the compromise and the reality of linking women with nature.

Bahuguna was among the first to coin the phrase ‘Ecology is permanent economy.’ Bahuguna’s words are taught today as sustainability, triple bottom line and creating shared value amongst business schools and researched and strategized in large companies.

Bahuguna was the man who mirrored the global view of the environmental development agenda. The United Nations’ (UN) Human Environment Conference of 1972 had taken place by then in Stockholm and the UN defined sustainable development by the 1980s. Few years into the future, the Chipko Movement (1973) became famous and Rio Earth Summit in 1987 contributed its bit to make the environment and its protection a part of the global conversation and compel nations to put it on their agenda. However, from discussion tables to the forests of the Himalayas, we needed activists like Bahuguna to spread the word and bring a sense of emergency to the issue.

The success of ‘Chipko Andolan’ lies in a few critical aspects. First is the use of the word ‘Chipko’ itself, meaning ‘to stick to what is important’ for the larger cause and literally be ready to sacrifice self for the larger good. The movement was trademarked by the images of women hugging trees and not allowing them to be cut. The women said if the trees were to be felled then they needed to be ‘felled’ as well. That sense of being able to lay down oneself in the path of destruction has been seen in movements across the globe such as the protests at Tiananmen Square in 1989, symbolised by the ‘Tank Man’ and the Burning Monk in 1963. But what was more difficult was to get women working at homes and engaged in multiple roles to step aside, take time out and prioritise a need such as environment. Here was a leader (Bahuguna) who was able to push the boundaries and bring people to understand the realities of an event that will have a long-term impact and which would not be visible immediately. Yet, he was able to take women out of their homes and into the forests and hug the trees to prevent their destruction. This ability, in an age with no fast communication means, has got to be a gargantuan task. This ability to put the cause before the self has been embodied in Indian activists for years but saw a reflection in common women for the first time.

Also read: ‘Saving Ganga became a movement only because of Bahuguna’s work’

Women and ecology have not been adequately understood by us. We understand that there have been women activists. In fact, the space of environmentalism is packed with women. Vimla Bahuguna (Sundarlal Bahuguna’s wife), Vandana Shiva, Gaura Devi, Salumaradda Thimakka and Medha Patkar are the shining examples. Yet, the link between women and the environment needs to be understood. Women very often face the brunt of changes made to the environment and, therefore, are the first few to understand the impact of environmental degradation. The issue is often centred around water with women being at the forefront of water management at the household level. Images of women walking miles with pots of water on their heads have been an Indian phenomenon, which has plagued the social fabric of the nation. The amount of time and energy that is invested by Indian women in fetching and managing water cannot be accounted for in a day that is already wrought with care activities. Girls are often taken out of school to accommodate the need for fetching water in the household and this vicious cycle leads to school dropouts, early marriages, low nutrition and low birth weights. Right from foraging forests for produce, to managing household firewood requirements, women are directly linked to nature on a day to day basis.

Let us not make the mistake of thinking that this is true for only the rural parts of India, as migrant labourers living in make-shift arrangements (what we typically call slums) also face similar issues. Women in slums need to travel long distances to get water and often use urban wastelands as toilets or spaces to gather firewood for cooking purposes. Hence, clearing any of these spaces has an immediate impact on women from these communities.

Today, activism is fed by technology and rightly so. We are able to use the power of communication to reach out, spread messages and educate people about issues. Hence something, as localised as the Aarey Colony issue of Mumbai, could become a national problem. Irrespective of whether citizens of Mumbai succeeded or not in their effort to save the Aarey forest, one needs to remember that the issue made national headlines. Therefore, it is progress in the right direction. But in the struggle to save the environment, we need to remember fighters such as Bahuguna, who were forced to do it the hard way.

(The author is Assistant Professor, TAPMI Centre for Inclusive Growth & Competitiveness at T A Pai Management Institute, Manipal)

Purnima Venkat is Assistant Professor, Strategy & Sustainability & Co-Chair, TAPMI Centre for Inclusive Growth & Competitiveness, T.A. Pai Management Institute, Manipal She may be reached on purnima.venkat@tapmi.edu.in

Purnima Venkat is Assistant Professor, Strategy & Sustainability & Co-Chair, TAPMI Centre for Inclusive Growth & Competitiveness, T.A. Pai Management Institute, Manipal She may be reached on purnima.venkat@tapmi.edu.in