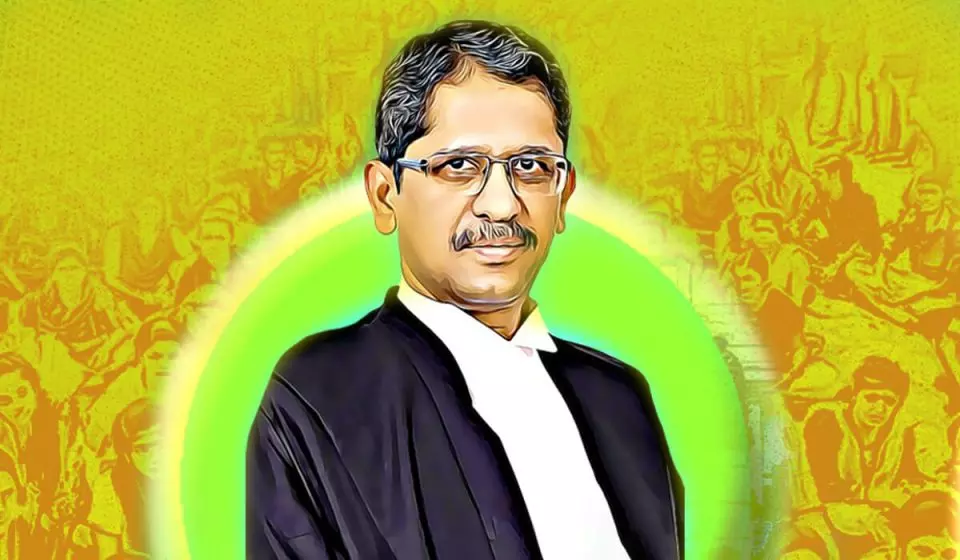

Justice Ramana’s rise to CJI post despite chequered legal history

In Part 1 of a two-part series, Justice K Chandru recaptures the colourful career of NV Ramana, from his student-activist days to elevation as India’s 48th Chief Justice

Justice Ramana’s rise to CJI post despite chequered legal history

The Story of Kashmir’s integration with India

In Part 1 of a two-part series, Justice K Chandru recaptures the colourful career of NV Ramana, from his student-activist days to elevation as India’s 48th Chief Justice

Uploaded 18 September, 2022

NV Ramana was perhaps the only Supreme Court judge who faced challenges to his appointment twice: one at the time of his elevation to the Supreme Court on the judicial side and two, at the time of his appointment as the 48th Chief Justice of India (CJI) on the administrative side. He had a colourful career both as a lawyer and as a political activist, before he retired on August 26.

Born in 1957 in a village in Andhra Pradesh, Ramana joined Nagarjuna University (Guntur) for his graduation in science and later in law. During his student days, he also dabbled as a news reporter for Eenadu daily, during 1979-80. After graduating, he enrolled as a lawyer before the Bar Council of Andhra Pradesh, in 1983.

While he was doing first year of law, there was a student’s protest, on February 13, 1981. An FIR was registered at the Mangalagiri police station against unknown persons but they described the accused as Nagarjuna University students. A charge sheet was filed on October 10, 1983 under Sections 147, 342, 427 and 324 of IPC before the court of the munsif magistrate, Mangalagiri, and NV Ramana was shown as accused No 4. All the protesters were described as absconders.

The magistrate issued summons twice, but the protesters did not appear in court. The matter was adjourned to February 15, 1984 and the case was listed on several dates thereafter. On November 27, 1985, when accused No 2 to 5 did not appear, the case was split and proceedings were carried out against accused No 1 alone. Accused No 1 was acquitted on July 4,1988 for want of evidence.

For the other accused, non-bailable warrants were issued. From 1987 to 1991, the case was adjourned 24 times. On May 8, 2000, non-bailable warrants were again issued against the remaining accused. In 2001, evidence was recorded in the absence of the accused and the assistant public prosecutor informed the court that the other witnesses were not available.

However, on January 31, 2002, the Assistant Public Prosecutor moved an application under Section 321 of CrPC to withdraw the case in the interest of justice as per Government Order Rt No 1961, dated 11.12.2001. On 31.1.2002, the trial magistrate gave permission for withdrawal of the case. Ramana was the additional advocate general of AP at that time.

Ramana enrolled as a lawyer in 1983 and was practising at the Magistrate Court, Vijayawada. He later shifted to Hyderabad and practised before the Central Administrative Tribunal and the High Court. He was subsequently appointed as Additional Standing Counsel for the Central government, Standing Counsel for Railways before the CAT as well as an Additional Advocate General of Andhra Pradesh.

Ramana was practising as a lawyer when NT Rama Rao’s Telugu Desam Party (TDP) came to power, from 1983 to1989. After a gap of five years, NTR came back to power in 1994-95. But his son-in-law N Chandrababu Naidu led a coup within the TDP and captured power in 1995; he was in power till 2004. Then, for 10 years, he was out of power and returned as Chief Minister in 2014, when Telangana was bifurcated from Andhra Pradesh.

Ramana was close to Chandrababu. The withdrawal of the criminal case against him was done during the first tenure of Chandrababu as CM. He was also appointed as Additional Advocate General during TDP rule.

After 10 years of practice as a lawyer, Ramana suddenly decided to look for a judicial office and applied for the post of Judicial Member, Income Tax Appellate Tribunal. He got selected and was given an appointment order in 1995, but he did not accept it.

It may be a coincidence that by the time the appointment letter reached Ramana, Chandrababu had become the Chief Minister. In November 1998, Ramana’s name was recommended by the HC collegium for being appointed as a Judge of the High Court.

At that time, he was only 41.5 years old, and had completed only 15 years of standing at the Bar. His taxable income (1998-99) was just ₹1.25 lakh per month.

The Intelligence Bureau (IB) sent a report saying: “He enjoys good personal/professional image. Nothing adverse against his character, reputation and integrity has come to notice, so far. He has also not come to notice for links with any political party/communal organisation. None of his relatives is either serving or has served earlier as judge in any High Court or Supreme Court.”

It is not clear how the IB said he had no political party links, especially when he was holding the post of Additional Advocate General, which to anyone’s knowledge had reportedly become a post of “spoil sharing” by successive ruling parties, both at the Centre and the state. The fact that a non-bailable warrant was pending against him surprisingly did not come to the notice of the IB. That he had dabbled in politics was also a well-known fact.

Activist and senior advocate Indira Jaising, in her write-up “A politically correct CJI retires” (The Leaflet, 26.8.2022), wrote: “He has never fought shy of admitting his political background. An earlier occasion when I had met him, when he was still a judge of the Andhra Pradesh High Court, at a seminar on women’s rights, he had a conversation with me in which he disclosed that he was a student activist and that during the Emergency, he had to remain underground.

“Justice Jasti Chelameswar and Justice Ramana. Both of them belonged to different camps but had a common political friend, the politician and former Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister N Chandrababu Naidu.

“I was hugely impressed by this one fact, which led me to conclude that political activism before becoming a judge was not such a bad thing after all.”

Ramana himself was quoted by Bar and Bench as stating that he was keen on joining active politics, but destiny had planned otherwise. What the whole world knows about his political leanings and connections, the intelligence wing of the Government of India had conveniently omitted in its report.

Since the non-bailable warrant on a pending criminal case was never brought to the notice of the HC collegium and the Supreme Court, and the IB Report remained silent, Ramana was appointed as a Andhra Pradesh HC judge on June 27, 2000, after a delay of nearly one-and-a-half years.

However, when the proposal for appointment came to the Supreme Court, the consultee judge, Justice M Jagannatha Rao, expressed his reservations. But when the proposal was sent again, approval was obtained from another consultee judge, Justice Akbar Basha Kathri, from the same state. After Kathri’s approval, Ramana’s name was sent for appointment.

Nevertheless, he was only 43 years old and was fortunate to have been recommended at an early age, when the practice was not to consider any name before a person completes 45 years. Appointment at such a young age was an assured way to reach the portals of high power at the Supreme Court.

After serving 13 years as HC judge, Ramana was posted as the Chief Justice of Delhi HC on September 2, 2013. From there, elevation to the Supreme Court was not that difficult. As per seniority, he was made a Supreme Court judge on February 17, 2014.

Anticipating his elevation, two advocates from Andhra Pradesh led by Manohar Reddy filed a quo warranto writ petition before the Supreme Court, questioning his appointment as a judge of the Andhra Pradesh High Court. They sought a direction from the Bar Council to cancel his enrollment as an advocate for the alleged suppression of the fact of non-bailable warrants pending at the time of his enrolment, which would have disqualified him.

It was too late to approach the Supreme Court, especially 12 years after his appointment. Justice Aftab Alam, who led the bench, dismissed the writ petition with a cost of ₹50,000 to be paid by each of the petitioners.

The Supreme Court held: “From the record it is evident that none of the members of the High Court or the Supreme Court Collegia was aware of the fact. The state government was equally unaware of the fact and so was the Central government, as is evident from the resume prepared by the Law Ministry as also the IB Report.”

The bench said that after appointment as a judge, if any suppression of facts relevant for appointment comes to notice, only the impeachment procedure will have to be resorted to. It also emphasised the need to balance ‘institutional integrity’ and the importance to protect the court from “uncalled-for attacks” and from unjust infliction of injuries on individual judges.

Having continued as a SC judge, NV Ramana became the 48th Chief Justice of India on April 24, 2021, in the line of succession and seniority. Ahead of that, he did not anticipate a new salvo aimed at him — not by any lawyer or litigant, but by the sitting CM of Andhra Pradesh, Jagan Mohan Reddy.

Jagan urged Ramana’s predecessor, Justice SA Bobde, to ensure that the state’s judicial neutrality is maintained. He alleged that Ramana was interfering in the affairs of the Andhra Pradesh HC and had been influencing the sittings of the High Court, including the roster of a few judges. He also cited instances of how matters important to the Opposition TDP had been ‘allocated to a few judges’, along with copies of orders passed in a few matters.

Jagan further cited an order passed by the Chief Justice of the High Court in writ petition No 16468 of 2020, filed by former Advocate-General Dammalapati Srinivas, staying investigation in the FIR lodged against Srinivas and a gag order on the press, against which an SLP (special leaves petition) was preferred.

“While the SC has been steadfast in ensuring no prior restraint on publication by media, a gag order on the media was passed in the above petition. Justice DVSS Somayajulu passed an interim order on October 16, the very next day of the gag order, staying all further proceedings arising from the Cabinet sub-committee report, even after being apprised that the matter was before the Union of India,” Jagan said.

Stating that the beneficiaries of both the high court judgments were clearly TDP politicians, Jagan alleged that Justice Ramana was a legal adviser and additional advocate-general in the previous TDP government. The CM said that the state government formed a sub-committee by GO no. 1,411 on June 26, 2019, to examine the allegations of “unbridled corruption, ruthless exploitation of natural resources, grabbing of lands from small and marginal farmers”.

After the sub-committee submitted its findings, referring to the amassing of wealth by TDP president Chandrababu Naidu and others by adopting various illegal means to the Assembly, the government forwarded the report to the Union government, urging a CBI inquiry. In view of the above, the CM urged Justice Bobde to consider initiating steps to ensure that the state’s judicial neutrality was maintained.

Addressing a press conference in this regard, Ajeya Kallam, CM’s advisor, told media persons why Jagan addressed a letter directly to the CJI. He said: “In larger public interest and in order to put to rest the speculations in a section of media concerning these developments, the government deemed it fit to officially speak on the above to ensure the dignity of all the institutions of the state is preserved. The Government of Andhra Pradesh filed Special Leave Petitions against the orders of Justice DVSS Somayajulu of the High Court staying all further proceedings of Cabinet Sub-Committee and the order of Chief Justice Jitendra Kumar Maheswari staying investigation and a gag order on the reportage of FIR filed against a former A-G and family members of a sitting SC judge in what is now being referred by Amaravati Land Scam.

“The government has apprised the recent happenings in the High Court and in particular reference to the intervention of a sitting Supreme Court judge, Justice NV Ramana, in the proceedings of the High Court.’’

He also said that the state government placed all the evidence along with a covering letter written by the CM to the CJI on October 8.

Normally, when complaints are sent to the CJI against the sitting judges of the Supreme Court, the CJI has to satisfy himself on the worthiness of the complaint and must order an “in-house enquiry”.

In an earlier PIL, the SC ruled: “The Chief Justice of India, on receipt of the information from the Chief Justice of the High Court, after being satisfied about the correctness and truth touching the conduct of the judge, may tender such advice either directly or may initiate such action, as is deemed necessary or warranted under given facts and circumstances. If circumstances permit, it may be salutary to take the Judge into confidence before initiating action.

“On the decision being taken by the Chief Justice of India, the matter should rest at that…It would thus be seen that yawning gap between proved misbehaviour and bad conduct in consistent with the high office on the part of a non cooperating Judge/Chief Justice of a High Court could be disciplined by self-regulation through in-house procedure. This in-house procedure would fill in the constitutional gap and would yield salutary effect.” (C Ravichandran Iyer, 1995)

When Jagan took this recourse prescribed by the judiciary itself, it was surprising Ramana got support to speak against the CM’s petition directly to the CJI.

Indira Jaising wrote: “In a system where there is a separation of power between the judiciary and the executive, the CM ought to have written to the Governor, who would have then sent it to the President, who is the appointing authority of judges. The President would then decide whether to forward the letter to the CJI for his comments. Instead, Jagan chose to communicate directly with the CJI.”

It is puzzling where Jaising got this new idea of a circuitous route even for sending a complaint, especially when the SC had ruled such petitions to be sent directly to the CJI.

On March 24, 2021, the SC issued a statement saying it had dismissed Jagan’s complaint against SC Judge NV Ramana, next in line to be the Chief Justice of India, stating that an in-house enquiry had been conducted into the allegations.

The court also stated that all matters dealt with under the in-house procedure are confidential and are not liable to be made public. The statement came just hours after reports said that CJI Bobde had recommended Justice Ramana, the senior-most judge after him, as his successor and the 48th CJI. His decision was in line with convention and norms of seniority. Thus, Ramana reached the highest portals of power despite heavy odds against him.

Part II | CJI Ramana: Media darling, government’s friend, nation’s ‘Manchivadu’

(Justice K Chandru is a former judge of the Madras High Court. After retirement, he writes extensively for leading newspapers and magazines.)

(The Federal seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. The information, ideas or opinions in the articles are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Federal.)