ASI eviction notice leaves 20,000 Tughlaqabad slum dwellers in despair

Most of the occupants are migrant worker families; the demolition will leave them homeless and sever a vital connection to their places of employment

The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has told the residents of a slum in Delhi’s Tughlaqabad to leave their houses, plunging the neighbourhood into fear and despair. Many locals claim they have been living there for over 10 to 15 years and this eviction is illegal.

“If this house was illegal, why are we paying electricity bills and why is the government accepting them? How come we were issued Aadhaar and Voter ID cards?” asked 29-year-old Roma, sitting with all documents in hand.

The locals are not claiming ownership of the land but asking for rehabilitation before eviction, says independent activist and academic Akash Bhattacharya.

What the law says

The Delhi Slum and Jhuggi Jhopri Rehabilitation and Relocation Policy, 2015, specifies that jhuggi-jhopdi (JJ) clusters, or slums, established before 2006 cannot be demolished without the provision of substitute dwellings. Also, a rehabilitation-eligible slum cannot be razed without a court order.

In its historic decision in Sudama Singh & Others vs. Government of Delhi (2010), the HC noted that affected persons have the right to a dignified relocation before being evicted.

Also read: G-20 meet: As Vizag gets facelift, 60 tribal families in slum face eviction

When a family living in a jhuggi is forcibly removed, each member loses a “bundle” of rights, the court noted, including the right to livelihood, shelter, health, education, access public utilities and transportation, and most importantly, live with dignity.

The Delhi Commission for Protection of Child Rights observed that the eviction of children without proper rehabilitation is a violation of their human rights. This observation and statement was given by DCPCR chairperson Anurag Kundu, stating that they will continue to monitor the situation.

Identities at stake

Roma is a domestic worker and a single mother of two. Her husband died a year back because of depression and other health issues. Roma questions the illegal tag on her house, and asks where the administration was when her family was paying electricity and other bills.

“My entire identity is related to this place. My Aadhaar card, voter card, and ration card have this address. After letting me stay here for nearly 10 years, how have these people woken up to the decision to call this place illegal?” she said.

Like Roma, hundreds sit outside their houses daily in the hope of drawing more publicity to their condition. Roma alleges that more than a thousand families were sent such notices, leaving all of them in fear.

The road that leads to the village seems deserted. The panic and tension in the air are palpable. The villagers noted how days passed after the notice was served to them, and every time a new face arrived, the villagers would start asking the person if he/she was from ASI.

Most of the occupants are migrant worker families from West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Jharkhand, and they are concerned that the destruction will not only leave them without a roof but also sever a vital connection to their places of employment.

Also read: As Adani wins makeover bid, a quick guide to Dharavi, Asia’s largest slum

Children worst sufferers

Mostly, the women in the village of Tughlaqabad, once they finish their housework or return from their place of work, sit outside somebody’s house for a chat. But for the past few days, they have had nothing but fear. From protests to visiting ministers’ houses to writing letters, they have done it all.

One such woman is Juhi, who betrayed no emotion while speaking about her condition. “I am done thinking about this situation. Since January 11, we haven’t slept a single night worrying about what would happen if our houses were demolished.”

Around 20,000 people will be affected by the eviction. Many of them are children, who are among the worst sufferers. They are finding it difficult to concentrate on their studies because of the stress and uncertainty of the situation.

The Bengali colony, which is close to the famous Tughlaqabad Fort, built in the 14th century and currently in ruins, primarily accommodates people from West Bengal and Bihar, both Hindus and Muslims. Some 20,000 people living in more than 2,000 homes will be impacted by the eviction, said locals.

Protection for Tughlaqabad Fort

The long legal battle that started in 2001, when petitioner SN Bharadwaj went to Delhi High Court to request that the historic Tughlaqabad Fort be protected from illegal encroachment by the land mafia, which was grabbing valuable land next to the fort walls, is what led to the ASI’s decision to order its demolition.

Fears that the fort might disappear were based on administrative indifference and land grabs that previously impacted other heritage sites such as Siri Fort and Qila Rai Pithora.

The Municipal Corporation of Delhi demolished the outer walls of Qila Rai Pithora to widen the road without understanding its historical value, according to renowned historian William Dalrymple, who mentioned it in his book City of Djinns. The edifice is still the only one from Delhi’s pre-Islamic era that is still standing.

“Though the petition is not very specific as regards the alleged unauthorized construction we think it would be appropriate if the concerned authorities look into the grievances in the proper perspective and take the necessary action as is warranted in law. We make it clear that we have not expressed any opinion as regards acceptability of the petitioner’s stand,” the High Court had said at the time.

The High Court decided the case after giving ASI a notice. Bharadwaj moved the Supreme Court in 2006 to request relief after receiving no response. He insisted that the ASI had received 4435 bighas of land from Delhi Development Authority as payment for maintaining and conserving the monument. All parties, however, continued to ignore the land grabbing.

The scope of the illegal land grab was to be determined; thus, the Supreme Court asked ASI to carry out an aerial and physical survey after taking the evidence into account. ASI insisted that to carry out the eviction, its staff needed police protection because of the threats they were receiving.

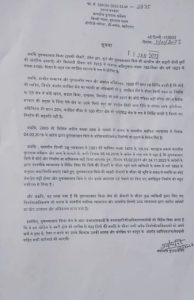

The ASI had given time till January 26 for the inhabitants to leave their homes so that demolition could take place after 20 years of legal conflict. When this piece was being written, they were yet to vacate the land and demolition had not begun.

Also read: Slum women of Delhi to be trained in fighting fires

“The fort has its national importance. It has been declared a protected monument. Therefore, it is the legal as well as the ethical obligation of the concerned authorities to protect this heritage site and to properly maintain it. Notwithstanding, over a period of time, the place is encroached upon and rampant illegal construction carried out by many people,” the Supreme Court had observed in its order in 2016.

The top court further noted that when the writ petition was heard, the High Court dismissed it with the remark that the ASI must investigate the complaints fairly and take any required legal action.

Locals allege years of bribery

The locals also claimed to The Federal that while buying the land and building their houses, they had bribed the police and ASI officials for years. “We have even maintained a diary to show how many times we have paid these people,” claimed a domestic worker.

She alleged that those officials have time and again threatened the locals against revealing the bribery. “Every time they came, we had to cough up at least Rs 500 for their ‘chai paani’. We were forced to give,” another added from the crowd.

“There should be no new development after 1993, and all existing construction should be demolished,” according to the warning ASI had put on the colony’s walls.

Also read: 20 years after Gujarat riots, victims live in temporary shelters with few rights

“My elder son’s 12th boards are approaching, but he has just given up because of the rising tension after the ASI served us the notice. How will the children cope with such a situation?” questioned 40-year-old Reena.

The Delhi Commission for Protection of Child Rights ordered ASI Delhi circle to rehabilitate children before any evictions after taking suo motu notice of the scheduled evictions.

The message said, “It is pertinent to mention that the order suffers from several infirmities. It speaks of no attempt or provision of rehabilitation of children. Taking away shelter from these families is nothing short of cruelty in such extreme weather in Delhi. Further, the children have their education which will suffer on account of this removal drive. It is tragic that the Archaeological Survey is not concerned about the well-being of the children.”