- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How in Haryana villages, dreams of a foreign job are landing young men at Russian battlefields

Families of young men claim they were duped by agents into joining the Russian forces, sent to the battlefront with barely 10 days' training. With two coffins arriving in October, parents and siblings allege the men were made to sign contracts in Russian that they understood nothing of.

In Madanheri village of Haryana's Hisar district, the silent coffin in the courtyard is both a witness to and the messenger of shattered dreams — dreams of a foreign education and job ending in a foreign war.Inside the house, 28-year-old Sonu Sheoran’s framed photograph is surrounded by incense sticks and marigolds. Until a few months ago, he was just another young man from...

In Madanheri village of Haryana's Hisar district, the silent coffin in the courtyard is both a witness to and the messenger of shattered dreams — dreams of a foreign education and job ending in a foreign war.

Inside the house, 28-year-old Sonu Sheoran’s framed photograph is surrounded by incense sticks and marigolds. Until a few months ago, he was just another young man from Haryana chasing the now-familiar route to a “better life” — a study visa, a short language course abroad and the promise of a steady job which paid in foreign currency. Instead, he returned home in a coffin on October 29, “killed on the Russia–Ukraine front”, allegedly after barely ten days of training.

“We thought he was going to study Russian and work as a security guard,” says his brother Vikas, clutching a sheet of paper filled with dense Russian text, which, he said, had come with the body. “He called once and said they had given him some documents, all in Russian. He couldn’t read a word. After that, they trained him for hardly ten days, gave him a gun and pushed him to the border. When he realised it was the war front, it was already too late.”

The family remembers the last call clearly, on September 3. Sonu, they recall, sounded anxious, but tried to reassure them. Days later, they got a phone call from a man, who the family says, identified himself as Sonu’s commander in the forces, informing them of the young man's death.

The body came later, along with a uniform and some documents in Russian. The family used Google Translate to understand just enough to identify the paper as a post-mortem report; it was a facility which Vikas says had not been available to his brother when he signed the contract that led him to his death, because his smartphone had allegedly been taken by the officers.

All that the family now wants is martyr status for their son. “We received no compensation, no official visited with the body. We had an acre of land. We borrowed Rs 5 lakh to send him abroad. Now we have neither Sonu nor savings,” laments Vikas.

Also read: Why Centre urging preference for ex-Agniveers in security jobs has triggered fear in Haryana

Unfortunately, Sonu’s is not a lone tragic narrative of its kind in Haryana. Across the northern belt of the state, families claim they are slowly discovering that their sons — who purportedly left home on paperwork promising education or civilian work — have been funnelled into Russia’s war with Ukraine.

On December 4, when Russian President Vladimir Putin reached India for a two-day visit, discussions on labour mobility were expected to be among the key items in talks between him and Prime Minister Narendra Modi — along with the reviewing of projects involving industrial collaboration, innovative technologies, transportation links, peaceful space initiatives, mining and healthcare. For families who believe their sons “trapped” at the Russia-Ukraine border, however, the only positive outcome that they can wish for from the meetings is news of the young men and hopefully, their safe return home.

On Wednesday (November 3), a day before Putin reached New Delhi, Hanuman Beniwal, member of Lok Sabha from Nagaur, Rajasthan, raised the issue of Indians allegedly enlisted in the Russian army in its war against Ukraine, exhorting the government to talk to its Russian counterpart to ensure their safe return. Last month, the Ministry of External Affairs had reportedly put the number of Indians serving in the Russian Army at 44, adding that it had taken up the issue with Moscow, urging them to stop the recruitment of Indian nationals.

This is not the first time that the issue of Indians being allegedly duped into joining the Russian army to fight in its war against Ukraine has drawn attention. According to reports, last year too, the Indian government had managed to ensure the early discharge and safe return home of many of the Indians allegedly tricked into joining the Russian forces. The matter had also been raised by PM Modi during his visit to Russia in July that year. Following this, reportedly 45 of the 91 Indians then believed to have been tricked into the Russian military were released by the country, which included those from Rajasthan, Telangana and Kashmir, most of them from poor families.

According to reports, the total number of Indians enlisted by the Russian armed forces so far has now touched around 170, of which 96 have been released, 16 are listed as missing and at least 12 have been killed.

In the same village as Sonu’s family, the Punias wait for a phone call that never comes. Aman Punia, 24, left around the same time as Sonu, lured by the same hope of better opportunities.

“Aman always wanted to wear a uniform,” says his younger brother Ashu Punia, standing outside their modest brick house. “He tried for the Indian Army like our grandfather [who had retired as subedar], but he couldn’t clear the selection. Then agents told him he could go to Russia, earn good money and support the family.”

Ashu added: “As soon as he reached Moscow, after spending some days working at a restaurant, he was told by the agents [who had helped him with the paperwork to travel to Russia] how he could earn more money. When he agreed, they took him to a camp.”

According to Aman’s family, he believed he was going to do some sort of security-related work, but had no idea that he would be purportedly deployed on the front.

“He told us over phone that the ‘security job’ meant training with weapons. They trained him for around ten days and gave him a gun,” claimed Ashu.

The one detail that haunts the family is how desperately Aman had tried to understand the contract he was signing.

“He was using Google Translate on his phone to read the contract that was in Russian,” Ashu says. “They saw him, snatched his phone and sent him into some forest area,” he claimed.

According to the family, this was narrated to them by Aman when he managed to make one call to them from a phone provided by his commander after repeated requests.

“Since then, there has been no call, no message. We don’t know if he is alive or dead. He just followed his dream of doing something big for the family,” Ashu murmurs. “And then he disappeared.”

The Punias survive on marginal farming and occasional labour work. The courtyard of their house has turned into a quiet meeting place of neighbours who keep asking the same question: how did a study visa end up as recruitment into a foreign war?

Also read: Living on the Zero Line: Why life is a daily struggle for residents of Bengal's Hakimpur village

Both Sonu and Aman had studied till class 12. The common practice for young men like them eyeing a foreign job, according to locals, is to contact an agent, who then procures a study visa for the candidate — usually for something basic and short-term, like a Russian language course — though at times, agents also manage to provide clients with work visas, claim families. Paperwork is handled by the agents, with families saying they are often in the dark about details like which institute or company their sons are purportedly joining in Russia. It is only now, when that tested route of a study visa leading to a job — however small, which pays in foreign currency — has instead made them collateral damage in a battle they understand little of, that parents and siblings are left searching for details.

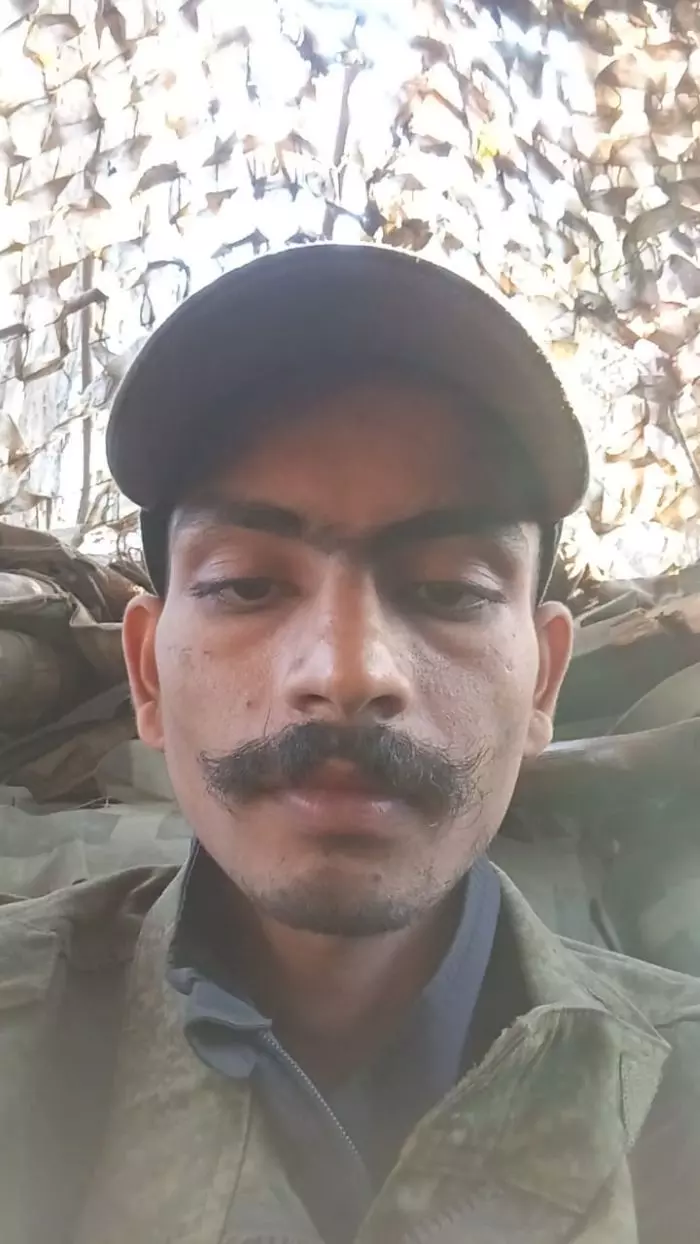

Aman Punia, believed by his family to be still trapped at the Russian war zone. Photo: By special arrangement

In Taimpur village of Rohtak district, Sandeep’s (identified by first name only) mother plays a grainy video, purportedly of her son crouched in a narrow ditch, his face smeared with dust. The young man whispers into the camera that he wants to come home. Behind him, several other men — whom the family believes are Indians — sit in silence, their eyes fixed on the ground.

“He went to study, like the others,” she says, hands trembling as she replays the clip.

In a report dated December 4, AFP Fact Check claimed that a purported video of an Indian, allegedly tricked into joining the Russian forces and pushed into the combat zone and seeking help to return home, which had been shared on social media and gone viral, was AI-generated.

Sandeep’s elder sister Jyoti, a postgraduate in Hindi, is blunt about how she sees it.

“He never went abroad as a fighter,” she says. “He was trapped. He wanted to earn some money, clear our debts, maybe buy a small house in town, some decent clothes, a vehicle. We are daily wagers. For us, even a few lakh rupees could have changed our lives. It was compulsion, not greed.”

Her mother has barely eaten since Sandeep’s last call, which, according to the family, was on October 1.

“He said they got food once a day, dropped by a drone,” Jyoti recalls. “He was in the jungle somewhere, wanted to run away, but didn’t know where to go. For more than a month now, there has been no contact. Every time the phone rings, we freeze.”

Also read: Why Bihar's Sakri residents are doubting Amit Shah’s promise of reopening state's sugar mills

The accounts emerging from the villages follow a disturbing pattern. Arrival in Russia on a study or work visa. A short training course, allegedly of around ten days, focused on combat basics. Phones allegedly confiscated, at times purportedly after the young men were caught trying to translate contracts written only in Russian. Immediate “deployment to frontline or forested areas”, often allegedly without clarity about location or unit and implicit or explicit threats that refusal to fight will land them in jail.

“They are made to sign contracts that they cannot read and cannot question,” claims the father of a 26-year-old, allegedly among those deployed by the Russian armed forces. “My son told me, ‘They [Russian officers] said if we don’t go as told, they will lock us up’. They’re [the Indian men] not soldiers; they are learning to survive by guessing which sound is a mine, which is a shell, which is a drone.”

Every news update of an Indian killed in Ukraine or Russia now hits these districts like a thunderbolt. In Hisar, Rohtak and Fatehabad districts, families count the days since the last call, bracing for the possibility that the next message from abroad may not be a voice note from their sons, but a confirmation of their deaths. The body of another Haryana resident, Karmchand from Kaithal district, had arrived from Russia on October 19, days before the coffin bearing Sonu's mortal remains.

Pushed to desperation, Sandeep’s uncle, Shree Bhagwan, along with families of other young men believed to have been deployed on the battlefield by the Russians and since missing, “went to Jantar Mantar in Delhi on November 3 to protest”. “We want the government to bring them back. Someone has to take responsibility before more coffins arrive,” says a worried Shree Bhagwan.

Protestors hold a banner with images of Aman and Sonu. Photo: Sat Singh

The plight of the families has also seen some action from local politicians.

Former Hisar MP Brijendra Singh wrote to the central government on October 11, flagging the issue as an “extreme humanitarian crisis” and specifically mentioning Sonu’s case and those of other young men from Haryana who had gone to Russia on study or tourist visas, but allegedly ended up in combat roles. The letter urged the Ministry of External Affairs to act urgently — to identify how many Indians were caught in such arrangements, to track the missing and to ensure safe repatriation wherever possible.

It was after this that that the family says the ministry confirmed Sonu’s death and informed them that his mortal remains were being transported to India after completion of formalities. For Vikas and his parents, the confirmation brought closure — an end to uncertainty, but also the final stamp on their worst fears.

In some cases, chief minister Nayab Singh Saini has assured families that the state is in touch with the Ministry of External Affairs and “making efforts” to bring back the young men who had landed in Russian combat zones, after going to the country on study or work visas. Police in some districts have been asked to question travel agents accused of routing migrants into risky or illegal arrangements and cabinet minister Anil Vij has publicly ordered strict action where fraud is proven.

Talking to The Federal, superintendent of police, Kaithal district, Upasana Yadav confirmed that they have received a couple of complaints against agents who had allegedly sent young men to Russia on a study visa, duping them into joining the Russian armed forces instead. “Every complaint of this nature is being taken seriously and action has been taken against some of the agents, but they are now out on bail,” said the police.

However, an agent, who claimed to be based in Madhya Pradesh, insisted it was the lure of more money which had landed the men from India into combat roles in the Russian forces. "No fraud has been committed. The men go there on study visas, but to work. They know they are being recruited into the Russian army and it is solely their decision [whether they want to join or not]. There are posters in all public places in Russia about recruitment drives by the armed forces. Nothing is hidden. Those who are joining are doing so voluntarily,” claimed the agent, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Also read: Why a section of Sikkim’s Dzongu residents have been waiting 10 years for a bridge to the world

The plight of the young men allegedly trapped in the Russian war zone does not exist in isolation. It is rooted in years of economic strain in rural households. In conversations at villages, having a son abroad carries enormous social prestige. Diaspora success stories — a cousin in Canada, an uncle in Europe — drown out quieter tales of failure, exploitation or deportation. Young men grow up hearing that true success lies beyond the border. Short videos and social media reels package foreign life as the fast road to luxury — high salaries, flashy cars, life in snow-covered cities. The risks of illegal contracts, unsafe work or conflict zones rarely make it to the frame. Most families borrow heavily — often from private lenders — to finance travel and agent fees. Once abroad, turning back seems impossible. Returning early means coming home to the same debt, plus bearing the stigma of “failure”. That pressure alone can probably push vulnerable young men into signing whatever is put before them, perhaps even contracts that push them into a war zone, especially if the nitty-gritties are shrouded in a language they do not understand.

And thus begins the trauma for the families of Aman, Sandeep and the many others who fear their boys are battling the bullet in a foreign country, all because they wanted a better life for themselves, their parents and siblings. As their ears strain for a phone call bringing news of their sons, their lips move in a silent prayer that it won’t be to inform them of death, like Sonu’s.