- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

What alleged deaths by suicide of school kids say of our awareness of mental health issues in young

Recent reports of purported deaths by suicide of school students, one as young as nine, triggered by alleged bullying by fellow students, have shocked the nation. Experts stress on the need to build children's emotional resilience, while training teachers to identify and help a child in distress.

When nine-year-old Amaira allegedly died by suicide at her Rajasthan school last month, there was immediate furore. The “high-performing” student of class IV at Jaipur’s prestigious Neerja Modi School had been purportedly facing persistent bullying by her classmates and it was alleged that her class teacher failed to respond to her repeated pleas for help.An FIR was filed, her parents...

When nine-year-old Amaira allegedly died by suicide at her Rajasthan school last month, there was immediate furore. The “high-performing” student of class IV at Jaipur’s prestigious Neerja Modi School had been purportedly facing persistent bullying by her classmates and it was alleged that her class teacher failed to respond to her repeated pleas for help.

An FIR was filed, her parents met senior government officials and state education minister Madan Dilawar seeking justice and parents’ organisations protested and urged for an impartial probe. Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) officials, who visited the school on November 3, reportedly found serious lapses in parameters such as safety, child protection and school response. According to media reports, the school was served a show cause notice by the CBSE, giving the educational institution a month to submit a reply as to why its affiliation should not be cancelled.

Meanwhile, the state government has assured a thorough and speedy investigation in the case. Addressing reports of tampering with evidence, Dilwar had told the media, "I will see the probe report and if claims of obstructing the probe are found to be correct, exemplary action would be taken against the institute. It is shocking that such an incident occurred at a reputed private school."

More than a month-and-a-half later, however, nothing concrete has emerged, except perhaps a hard lesson for parents that they can’t take their children’s safety in school for granted, irrespective of how reputed or exclusive the institution appears to be. And to be vigilant for signs of distress in the child and take action if needed.

Unfortunately, Amaira’s was not the only case of its kind in Rajasthan, or in the country, in the recent past.

Days after the nine-year-old’s alleged death by suicide, in Rajasthan’s Karauli district, 14-year-old Ankit Gujjar was found hanging from a tree on November 20. A purported suicide note alleged harassment and torture by school teachers and administrator.

On the same day in Delhi, Shourya Patil, a 16-year-old class X student of the reputed St Columbus School, allegedly jumped to his death at a metro station while returning from school. Again, a purported suicide note mentioned bullying and threats from teachers.

Earlier, in April this year, 17-year-old Kishore had reportedly died by suicide in Chennai, after allegedly enduring constant bullying from classmates over his appearance.

While in recent years, there has been greater attention given to students’ continuing struggles with mental health issues in the country’s premier higher education institutes, such as the IITs and Indian Institute of Management (IIMs) — amid a worrying rise in suicide cases — with an SC appointed national task force (NTF) being set up in March, on “mental health of students and prevention of suicide in higher educational institutions”, the deaths of Amaira, Ankit, Shourya and Kishore have now forced us to question our awareness about mental health issues in the very young.

According to the data released by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), student suicides accounted for 8.1 per cent of all suicides in the country in 2023; a significant rise from the 6.2 per cent recorded in 2013. The NCRB data reveals a 65 per cent rise in the number of student suicides in the country between 2013 (8423 suicides) and 2023 (13,892 suicides), which is higher than the percentage rise in total suicides in the country — 1,34,799 in 2013 to 1,71,418 in 2023, a rise of 27 per cent.

The data on student suicides includes those at higher educational institutions. While mental health experts attribute the rise in student suicides in the country to likely academic competition, unemployment fears, fiscal distress, family pressure, bullying and lack of robust mental health support systems, the first three or four seem more true for students of higher educational institutions than young school-going children.

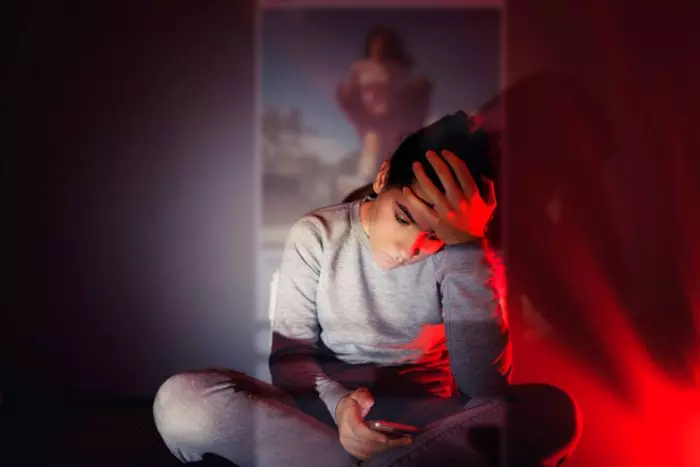

Bullying or any other behavioural issue may just be a manifestation of a deeper distress, self-doubt or fear of failure. While some may handle the pressure by targeting others or projecting a fake public persona, others may withdraw. Photo: iStock

“The only way forward is to recognise that bullying is happening in our schools and higher educational institutes and find ways to mend it. Most often, we tend to brush it under the carpet,” claimed Dr Anindita Bhattacharya, psychotherapist and visiting clinical psychologist at Bengaluru’s Narayana Health and Modern Health.

Talking about Amaira’s case, she added, “If some child has been actively asking for counselling, then it needs to be attended to, whether by parents, teachers or school counsellors. Suicide at this age is unthinkable, but it is happening.”

According to the psychologist, “bullying is internalised at different levels in children between the ages of, say, nine to 18. There is an urge to fit in. They feel isolated in class when they are excluded from popular groups in schools. They internalise the shame of exclusion and believe they don’t belong. And have a feeling that everybody else is making fun of them, which seems to be the case here [in Amaira’s case], as she was [allegedly] repeatedly being teased. Self-doubt begins to creep in.”

For Amaira, Bhattacharya reasoned, “probably death by suicide appeared to be a way of stopping the pain which had become unbearable; kids who internalise pain often engage in self-harm”.

Remembering the nine-year-old as a “happy, cheerful child and an all-rounder”, Amaira’s aunt, Deepali Dev, in conversation with The Federal, claimed “she never approached her teacher over minor issues, although she was being bullied for several months and her parents had complained to the teacher and coordinator about the issue at parent-teacher meetings. But no action was taken”.

Dev added: “According to her classmates, she had told one of the boys at school that she loved him. Amaira insisted, however, that she had just said ‘hello’ to the boy, for which she was mocked and made fun of. She had been crying at home.”

Referring to reports of CCTV footage collected from the school showing Amaira initially behaving normally on the day of her death, her aunt alleged, “Around 11 am, her classmates started showing her something on a slate, which left her disturbed. She approached the teacher five times in the last 35 minutes [of her life] asking for help; however, she was not offered any support and was dismissed. The fifth time, she was seen leaving the conversation mid-way and running up the stairs…”.

The Federal has reached out to the school over email for a response. The article will be updated if a response is received. The Federal has also reached out to Rajasthan education minister Madan Dilwar for comment on the status of the probe in the case. The article will be updated if a response is received.

Also read: Why Delhi moms across economic and social groups are losing out to a common fear

Interestingly, India is not the only country waking up to the need to address mental health anxieties in the pre- and early teens.

In south Australia, an anonymous online survey of more than 130 teachers conducted by Dr Samantha Schulz, an associate professor of sociology of education at the University of Adelaide, between February and April 2024, found teachers identifying a heightened use of misogynistic language and behaviour by male students, some as young as five.

In what could be a reflection of a real-life crisis, the 2025 Netflix web-series Adolescence, which showcased a 13-year-old boy’s arrest for killing a female classmate, precisely captured the dilemma and pressures which children find themselves in.

Counselling psychologist and founder of the healthcare and education NGO, Rajbala Foundation, Satish Kaushik, highlighted the dearth of counsellors in Indian schools. “Bullying is more of a delinquent behaviour and sometimes has a very severe impact on the psyche of children. We don’t take bullying and other mental health issues seriously owing to a lack of awareness about their impact, taking behavioural changes casually,” he cautioned.

According to mental health experts, while there is a need to equip children with life tools for emotional equilibrium, better interpersonal skills and increased concentration, adults, especially teachers, too need to to be trained to handle a child in distress. Photo: iStock

According to Bhattacharya, bullying is a nuanced issue, with both bullies and those being bullied requiring strong mental support.

Talking about children’s exposure to social media and OTT and their impact on behaviour, she added, “The presence of explicit sexual content on OTT, emoticons like dynamite emojis and others, content creators who glorify dominance and denigrate empathy, rise of manosphere, sexist language and slurs that at times draws appreciation [on social media], all add to it [behavioural issues]. There are no filters, there are hate speeches, anger, misogynist approaches and students have easy access to all of these. They often misinterpret them as a sense of power and identity. Not to forget the impact of online games, such as the Blue Whale challenge a few years back, an online game, which set 50 tasks over 50 days, culminating in death by suicide.”

But bullying or any other behavioural issue may just be a manifestation of a deeper distress, self-doubt or fear of failure. While some may handle the pressure by targeting others or projecting a fake public persona, others may withdraw.

“Students of classes X, XI and XII are under tremendous pressure regarding their careers. Additionally, when children are forced to take up subjects which they don’t like, they go into a shell as they are unable to cope with their parents’ expectations. A student of class XI stopped smiling after he took up science under pressure and ultimately could not even take the [higher secondary] board examinations,” recalled Mandira Das, who teaches business studies at Jaipur’s Tagore Public School.

The pressure of coping with school work, however, may begin early, though it may go undetected and unaddressed.

“At times, we hear children in kindergarten (three-to five-year-olds) saying they are bored in class. We laugh it off,” confided Aprita Chatterjee, a teacher in Jaipur’s Vidyaashram School.

But all these may be silent pleas for help.

"In these growing-up years, especially from the age of 10 through their teenage years, young children are vulnerable. They feel things intensely and often find it hard to manage their emotions. The prefrontal cortex of the brain, which is responsible for emotional management, is not fully developed as it is often the last part to mature. This makes them respond to stress in different ways, increasing their chances of developing stress-related mental illnesses such as anxiety and depression,” cautioned Bhattacharya.

She added: “Recognising possible triggers and practising effective coping techniques can help children deal with stress. Adults need to recognise these traits and help regulate emotions. Stress could also lead children to take more risks and these could be either negative or positive.”

Also read: Students schemes, tree plantation and blood donation to census, poll duty — what’s keeping teachers

In September this year, the Rajasthan high court issued notices to the Centre and the Rajasthan government, based on a public interest litigation (PIL) seeking appointment of counsellors at all government and private schools, colleges, universities and coaching institutions in the state and establishment of mental health centres.

The Delhi government, in 2018, had introduced the ‘Happiness Curriculum’ for students of pre-primary to class VIII. The course included daily lessons in happiness; creating moments of joy through story-telling, yoga and meditation and teaching children to take pride in their work. In 2025, the “Happiness Curriculum” gave way to the ‘Science of Living’, a new approach that addresses the real challenges students face in our hyper-digital world. According to mental health experts, the attempt is not just about making students happy for a while, but equipping them with life tools for emotional equilibrium, better interpersonal skills, and increased concentration.

But there is also a need to train adults, especially teachers, to be able to handle a child in distress.

"Teachers’ education curriculum should include mental health components and behavioural science, so that they are able to identify a kid in distress and raise red flags whenever and wherever necessary. Teachers also need to be careful themselves as they too may be working under stress,” cautioned Bhattacharya.

Meanwhile, in Amaira’s case, answers are still awaited.

“Our focus is to ensure justice for Amaira and her family,” said Ashutosh Ranka, founder, Parivartan, an NGO, which works for students’ well-being and which is spearheading protests in the case. “We have a plan to visit various private schools of Jaipur to ensure compliance with CBSE guidelines related to safety, security and mental health of students.”