- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Akshaye Khanna’s jig to Saiyaara’s heartbreak appeal — how 2025 brought in ‘meme era’ to Bollywood

In the digital creator-led economy, if a line hasn’t migrated to Instagram and been repurposed 10,000 times as a reel template, it effectively doesn’t exist. By extension, the film or show itself risks vanishing. But does that translate into a neglect of cinematic value?

For those of us who attained adulthood in the ‘90s and 2000s, cinema and its adjacent narratives were the languages we spoke fluently. Phrases and dialogues like ‘Bade bade deshon mein chhoti chhoti baatein hoti rehti hain, Senorita [Such small or insignificant incidents often take place in such big countries]’ (Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge, 1995); ‘Kuch Kuch Hota Hai hai Rahul, tum...

For those of us who attained adulthood in the ‘90s and 2000s, cinema and its adjacent narratives were the languages we spoke fluently. Phrases and dialogues like ‘Bade bade deshon mein chhoti chhoti baatein hoti rehti hain, Senorita [Such small or insignificant incidents often take place in such big countries]’ (Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge, 1995); ‘Kuch Kuch Hota Hai hai Rahul, tum nahin samjhoge [There is a feeling, Rahul, you won’t get it]’ (Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, 1998); ‘…Teen guna lagaan dena padega [You will have to pay thrice the due tax]’ (Lagaan, 2001); ‘Aunty mat kaho na [Don’t address me as aunty],’ (Hum Paanch, a television series that first was aired in 1995); ‘Andhera qayam rahen [Let the darkness prevail]’ (Shaktimaan, a television series first aired in 1997) etc were not just applause eliciting lines in a packed theatre or a cozy drawing room, they were the Morse code of a generation.

These dialogues shaped pop culture, designing the very way a generation interacted, for effect and impact.

Today, however, the metric of relevance has undergone a sea change. If a line hasn’t migrated to Instagram and been repurposed 10,000 times as a reel template, it effectively doesn’t exist. By extension, the film or show itself risks vanishing. In the digital creator-led economy, we no longer judge an artistic endeavour solely by its cinematic value or its message. It needs to rate high on the meme-worthy scale and its ‘meme-ability.’ If it can’t be made into a meme, it can’t make the moolah. And for the Indian entertainment industry, 2025 seems to have heralded the rise of the ‘meme era’ as never before.

Also read: How fresh finds, research progress made 2025 a significant year for science and technology

The numbers are talking. The most recent instance is the film, Dhurandhar. Actor Akshaye Khanna’s unscripted dancing to the Flipperachi track has been recreated in more than 91,600+ reels on Instagram. Celebs like Shilpa Shetty, Saina Nehwal and even official handles like the Delhi Police have jumped on the bandwagon.

While the film boasts an A-lister like Ranveer Singh, on social media, it’s the chief antagonist — Akshaye Khanna — who’s been sustaining the attention momentum. The film has raked in Rs 800 crores globally. Khanna’s impromptu jig, plus the earworm of a track, piqued interest like nothing else.

A scene from Dhurandhar.

Mauli Singh, film publicist and founder of Loudspeaker Media, has yet to watch Dhurandhar, although she intends to catch a show sometime. “But I have been seeing Dhurandhar memes everywhere, my [social media] timeline has been flooded by them,” she says.

So, has 2025 been the year of memes for her?

“Absolutely!” says Singh, adding, “they [memes and reels] have the potential to go really viral and have far more reach than traditional media outreach”.

Also read: GDP growth rebounds, but average Indian’s living standard dips — How Indian economy fared in 2025

Akshaye Khanna’s dance memes, though one of the most trending, are definitely not the only Bollywood- or OTT-series- inspired reels to have gone viral on social media in 2025.

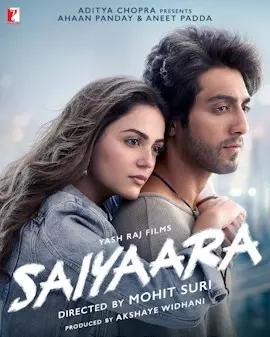

Earlier this year, the Saiyaara effect had people sobbing on camera as they watched the film or gave their own renditions of heartbreak. The title song alone has over 1.4 million reels on Instagram. A Mumbai-based senior entertainment journalist recalls being told of a member in the audience who purportedly told her companion towards the end of the film, “I'm going to be crying right now, just shoot my video”.

Meanwhile, Raghav Juyal, playing the unhinged Emraan Hashmi fan in this year’s Netflix series The Ba***ds of Bollywood, inspired 420,000+ reels on Instagram by belting out ‘Kaho Na Kaho’ (from the 2004 Hashmi-starrer, Murder) at the top of his voice.

“With the all-pervasive influence of social media, the publicity of a film, and also its reception, has taken a new form,” says Yasir Abbasi, author and film enthusiast. He adds: “Now reels and memes have the maximum reach and impact. Memes evoke instant reactions, have great recall value and large-scale forwarding ensures great visibility. There are so many films I haven’t seen, but I know about them all thanks to the memes.”

A poster of the film Saiyaara. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Contrast the loud yin of the meme-led narratives with the quiet yang of the year’s content-driven stories. Superboys of Malegaon – based on a true story; Homebound, which made it to the Oscar nomination shortlist, yet couldn’t find a place on anyone’s Instagram feed. Then there was Agra, directed by Kanu Behl, which takes an honest look at the repressed Indian middle class. None of these stellar films translated to the reel template. After all, it is nearly impossible to translate repressed angst or a scathing commentary on patriarchy into a loud, gimmicky 30-second reel. While feted by critics, they left no trace on social media.

For much of Bollywood and adjacent narrative led-industries, however, there is a new formula in place and they are not ashamed to use it. If there is no 30-second re-creatable hook, the film/show/narrative will sink. Forget plot, nuance or cinematic artistry. They now need something that will feed the algorithm.

It may be a fad, concedes Abbasi, “but right now it’s a mighty effective tool for promotions”.

Also read: Politically vocal but electorally outfoxed — what 2025 has been like for India's Opposition parties

Circle back to the ’90s, 2000s, and even the 2010s. Reviews, film clubs, and good old word of mouth were the tools that helped a film gain momentum. A recommendation from a film professor would lead to a hunt for the film, sourcing it by any means possible. But today, many seem to have stopped asking questions like “Is the film good? Is the script worth adapting to the screen?”

This cultural shift is what the famous German philosopher Walter Benjamin feared the most. We all know that imitation is the best form of flattery, and the recreation of art has always been a democratic right — no matter how much Benjamin decried the loss of the “aura” in his seminal 1935 essay, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’.

Unfortunately, most reels are not even imitations with a unique twist, a satire, or a hot take. They are blind reproductions, undertaken because the algorithm flagged them as ‘trending’. The goal isn’t to honour the art, but to rake in the requisite hits, views, and engagement numbers.

“Cinema has always been a commercial medium and naturally the present-day makers have adopted strategies to tap into the current trends,” reasons Abbasi.

What is worrying, however, is that we are now prioritising the ‘hook’ over the ‘heart’ of the narrative, creating films and shows that are inherently disjointed. If the ‘hook-ability’ evolves to be the sole criterion for green-lighting a project, then will we ever see another magnum opus? Will something on the scale of Mughal-e-Azam (1960), which took 16 years to make, ever grace the 70mm screen again? Or even a simple film like 12th Fail (2023), directed by Vidhu Vinod Chopra, which sat with him for over four years, going through more than 130 drafts. Not sure if the piercing glare of Prithviraj Kapoor and his gruff baritone could be translated to a 30-second template, or the agony and struggle faced by Vikrant Massey would make it to the algorithm.

As we doomscroll into the ‘meme era’, a question begs to be asked: What exactly are we gaining as we pander to the ‘hits and views’ trap? We might be at the receiving end of a film’s onslaught on our feed for a week, but will it stir the soul or stimulate the conscience? It seems like a poor trade-off. Perhaps producers, writers, and directors need to look beyond the 30-second lens and aim once more for the ‘aura.’ While it may not elicit the instant moolah that memes do, what we gain instead are everlasting stories — a true cinematic legacy.