- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

50 years of BMVSS: How the Jaipur Limb parent company rehabilitated 2.3 million since inception

The Shree Bhagwan Mahaveer Viklang Sahayata Samiti, established by retired bureaucrat and former SEBI chairman Devendra Raj Mehta in 1975, provides free prosthetics, wheelchairs and more to patients, many of whom are below poverty line. The intangible gifts? A life of dignity and self-reliance.

The waiting area of the Shree Bhagwan Mahaveer Viklang Sahayata Samiti (BMVSS) in Jaipur’s Malviya Nagar area was crowded with people patiently awaiting their turn to be called in for consultations. Hope shone bright in their eyes — amputees, those with hand injuries or requiring the support of a crutch to walk and children with spinal disorders. One such child lay on the floor, crying,...

The waiting area of the Shree Bhagwan Mahaveer Viklang Sahayata Samiti (BMVSS) in Jaipur’s Malviya Nagar area was crowded with people patiently awaiting their turn to be called in for consultations. Hope shone bright in their eyes — amputees, those with hand injuries or requiring the support of a crutch to walk and children with spinal disorders. One such child lay on the floor, crying, while her parents waited for their turn.

As names were called in, the waiting people one by one made their way to the next room, to be fitted in with prosthetic limbs, or receive wheelchairs, crutches, hearing aids… But the wait was not just for tangible aid; for the people in that room, it has been a wait made worthwhile because of the promise it offered of a life of dignity, self-respect and self-reliance, including in mobility, in pursuing their aspirations and earning a living.

“The process usually takes just two days,” said a recipient of a prosthetic limb as they left the BMVSS centre. “There is no chaos here, almost everything is streamlined.”

A non-governmental organisation which completed its 50th year in 2025, BMVSS was established by retired bureaucrat and former chairman of Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), Devendra Raj Mehta, in 1975. The parent body of the low-cost prosthetics, Jaipur Limb, it has rehabilitated over 2.3 million people since its inception, providing prosthetics, callipers, crutches, tricycles, wheelchairs and hearing aids free of cost to beneficiaries, many of whom are below the poverty line. Recipients are given free food and lodging at the centre while they are fitted with prosthetic limbs, with BMVSS also providing rehabilitation assistance to some of them.

The organisation’s Stanford-Jaipur artificial knee joint was named one of the 50 best innovations of 2009 by Time Magazine.

Manjit Kumar Girin, a resident of Bihar’s Gopalganj, was all set to catch the night train back home on November 21, having been fitted with a Jaipur Hand earlier in the day. “I came here yesterday and was fitted with the Jaipur Hand. I have to undergo some physiotherapy and will leave tonight,” he told The Federal. “It isn’t as flexible as my other hand, but I will make it work,” added Manjit, as he opened and closed the fingers of his ‘new’ hand, slowly but steadily.

Manjit had lost his right hand in an accident in November 2024 while operating a JCB Machine in a factory in Gujarat’s Dahod district. According to him, the machine malfunctioned and fell on him, resulting in injuries to his hand and waist and fractures in his leg. “The factory owner didn’t even come to see me, let alone offering any compensation or even the cost of treatment,” he alleged.

Manjit Kumar Girin, who lost his right hand in an accident last year and was fitted with a Jaipur Hand in November. Photo: Rakhee Roytalukdar

According to Manjit, others from Gopalganj who also worked in the Gujarat factory, took him to a hospital in Ahmedabad for treatment, where doctors said they would have to amputate his right hand. And so he returned home to Bihar, having lost a hand and his job. Additionally, the fracture in his leg confined him to bed for two-and-a-half months, he recalled. Being the eldest son in a family of six, including his parents, his earnings had been important for them.

However, Manjit, who is also enrolled in a college in Bihar, did not lose hope.

“While browsing social media for possible treatments, I suddenly came across this video about Jaipur Foot and also got to know about Jaipur Hand. I saw how people who had had legs amputated because of accidents or diseases were walking again. It wasn’t just about fitting the limb, but restoring their dignity. I immediately made up my mind to come to Jaipur,” he recalled.

Around the same time that Manjit was receiving a Jaipur Hand in India, in faraway Mozambique’s Nampula city, a little polio-affected boy of five was being fitted with a Jaipur Foot at a BMVSS camp being held there in November-December, and learning to walk again. According to Prakash Bhandari, BMVSS media advisor, who is helming the camp, at least 17 prosthetic fittings are being done on a daily basis there.

Also read: International Day of Persons with Disabilities: Why India still lacks inclusive public spaces

The origin story of Jaipur Foot began with a chance meeting between Ram Chandra Sharma, a sculptor adept at recreating human likeness and Dr Pramod Karan Sethi, an orthopaedic surgeon in Jaipur, in 1968. Sharma saw Sethi working with accident victims who had lost their limbs, fitting them with artificial ones. Jaipur's biggest government-run hospital, Sawai Man Singh (SMS), produced only a few such limbs every year at the time, based on American and German designs, as it was a time and skill-intensive process and imported limbs were expensive.

Although these artificial limbs were working well in the West, they were not suitable for Indian amputees, recalled Mehta.

Indians squat, sit cross-legged, negotiate rugged terrain and walk barefoot, so it was imperative that the prosthetic was durable, flexible, water-proof and looked like a normal human foot, so the recipient could use it with or without a shoe.

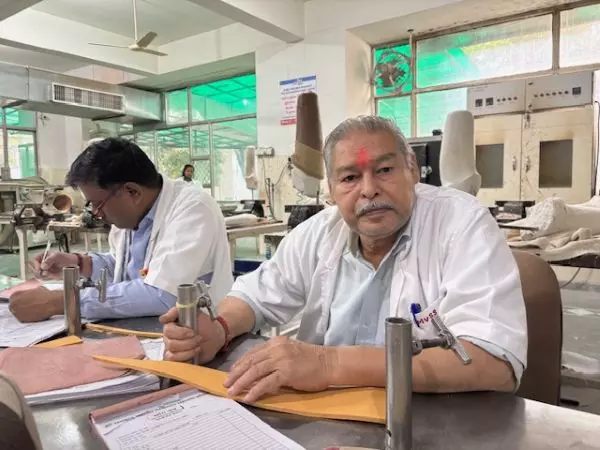

The BMVSS laboratory, where the Jaipur Limb is manufactured. Photo: Rakhee Roytalukdar

Over the next two years, Sharma, Sethi and other doctors worked on the design of a prosthetic suited for the unique needs of India, and also the socio-cultural needs of Sethi’s patients, most of whom were poor and engaged in physical labour. The loss of a limb affected their livelihood and they required a low-cost prosthetic that could be manufactured and fitted quickly, using a simple process and with locally available materials.

One day, while getting his bicycle’s flat tyre repaired, Sharma noticed a mechanic retreading a truck tyre with vulcanised rubber. Sharma requested the mechanic to cast a foot in this material. The vulcanised rubber made the foot more flexible than earlier models, but it shredded a few days later, said Bhandari.

The doctors and Sharma had also been refining the Solid Ankle Cushion Heel (SACH) foot, a Western design consisting of a rigid wooden block covered in rubber. The wooden block ran from the ankle to the instep and was not flexible. While tinkering with the design, the duo took off the wedges and converted the single wooden block into two. This increased flexibility. The doctors merged the idea of the vulcanised rubber foot and the reworked SACH foot. This was the first successful design of the Jaipur Foot. To make the foot wearable for both above and below-the-knee amputees, the team used either a shank and brace or a shank, brace and knee joint to connect the foot to the patient’s limb.

Meanwhile, in January 1969, Mehta, then the Jaisalmer collector, met with an accident while travelling to Pokhran in a car. His right femur was shattered into 43 pieces. In Jodhpur, where he was first taken for treatment, the doctors' first thought had been to amputate his leg, recalled Mehta. Although they eventually managed to save his leg, Mehta spent five months recovering at Jaipur's SMS hospital, where he had later been shifted. It was here that he met Sethi and Sharma, who were then working on the design of the Jaipur Foot.

"While recuperating at the hospital, I would often observe the travails of other accident victims. I knew I had received good care because of my position and influence. But I wanted to find a way to help poor patients and six years later, BMVSS was born,” Mehta recalled.

Also read: Why law banning commercial surrogacy has landed women who rented their wombs in greater misery

Between 1968 and 1975, when BMVSS was launched, only 50 patients had been fitted with the Jaipur Foot, show official records. The number grew to 437 the following year, in 1976 and gradually increased to over 10000 by 1985. In 2022-23, BMVSS rehabilitated 88467 people, according to the organisation’s records. In 2024-25, the total number of limbs fitted was 40078. On average, across its 37 centres in India and outreach camps, BMVSS rehabilitates an estimated 300 people daily, either by fitting them with artificial limbs or providing them with mobility-assisting devices. Over the years, it has organised 120 camps in 42 countries, including Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, the Philippines, Syria, Congo, Sudan, Vietnam and Rwanda.

The USP of BMVSS, according to the staff, is that anyone, rich or poor, can walk into the organisation's premises at any time without any prior appointment or registration. Here, even the guard on duty may admit patients and the doctors would examine them during working hours.

Retired bureaucrat and former SEBI chairman Devendra Raj Mehta who set up BMVSS in 1975. Photo: Rakhee Roytalukdar

“The patients who come here are from poor families; most do not know how to read or write. How do you expect them to register themselves and book appointments? They are scared of the formal system. So we must operate in a way that puts them completely at ease,” explained Mehta.

He added: “We have an open-door policy. We provide them with food and a place to stay. They only sign one piece of paper at the end of their visit to record the type of assistance they have received.”

At the Malviya Nagar campus last month, two saffron-clad ascetics from Delhi waited for a consultation for one of them, who had been using a wooden seat on wheels to move, as one of his legs had been amputated. “We had been to Khatu Shyamji Temple in Rajasthan. On the train, someone told us about this place. So we came here today and are waiting for a wheelchair. Officials said they would first finish off with those who need limbs and then give us the wheelchair,” said one of the ascetics, talking to The Federal.

According to BMVSS staff, most patients need as little as three hours to be fitted with a prosthetic limb and, barring in a few complex and time-consuming cases, are able to return home in one to three days.

In keeping with its focus on social rehabilitation of patients, BMVSS provides aid like sewing machines and tea-stall kits to help patients become self-employed. “Our ethos is of help, not charity. These people are our brothers and sisters. When they leave here, they are changed. They have regained their self-esteem,” said Mehta.

Interestingly, some technicians now a part of BMVSS were former patients.

Shree Krishna, a Jaipur Foot recipient, who has worked at the BMVSS for 40 years. Photo: Rakhee Roytalukdar

Shree Krishna, whose family is from Uttar Pradesh’s Unnao district, has been working at the Jaipur centre for over 40 years. The 70-year-old had lost his right leg following a poisonous insect bite when he was just 10 years old. After being fitted with a prosthetic at SMS hospital, he received training in manufacturing and fitting limbs and was absorbed in the organisation. “I have become a Jaipur resident, built my house here. I have retired but still work here. There is so much love and empathy at BMVSS,” he said.

About his work, Krishna said, “Many things have changed over the years. Technology has improved. Earlier, aluminium and plastic were used for joints. Now, High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) is used, which results in seamless joints and very strong sockets.”

Another technician, Girma Prasad, 69, originally a resident of Balaghat in Madhya Pradesh, has also been working here for more than 40 years. Prasad had first come to BMVSS as a patient in the early ’70s after losing his right leg in an accident and stayed on, receiving training to join the organisation.

Also read: Why Delhi moms fear their children are becoming collateral damage to the city's smog apathy

Over the years, to technologically upgrade its prosthetics, BMVSS has entered into partnerships with Stanford University, MIT, Cambridge, Santa Clara University and others. The organisation also has a high-powered technical committee to guide its research and development.

According to Dr Pooja Mukul, technical consultant at BMVSS, the organisation depends heavily on user feedback. “It always starts with what the patients want, how they want it and what is appropriate for them,” she said.

Time Magazine in its fall 1997 issue had written, "The beauty of the Jaipur Foot is its lightness and mobility — those who wear it can run, climb trees and pedal bicycles and its low price."

Girma Prasad, another staff member who was a former patient. Photo: Rakhee Roytalukdar

At this time, the production cost of the Jaipur Foot was less than $5. Even now, according to industry estimates, while the production cost of a below-the-knee Jaipur Foot would be around Rs 6,700 ($74.40), the same artificial prosthetic limb would cost $15000 in Western countries.

“Over the past 50 years, the growth has been phenomenal. To ensure maximum utilisation of funds, BMVSS has kept administrative expenses low. Average administrative and overhead expenses account for 3.6 per cent of the organisation’s total expenditure, considerably lower than the average for the non-profit industry. Our belief is to function frugally,” said Mehta.

Talking about the organisation’s funds, he added that what started with a corpus of Rs 4 lakh in 1975 now runs into crores. A significant portion of BMVSS funding comes from government institutions and a mix of large donors such as Sir Dorabji Tata Trust, Azim Premiji Foundation, Nomura and Deutsche Bank.

The organisation has also received appreciation and commendation from many over the years.

Dennis Francis, a diplomat to the United Nations (UN) from Trinidad and Tobago, who also served as the president of the UN General Assembly in 2023-2024, wrote in the visitor's book at BMVSS after visiting the facility last year, "I am lifted by visiting Jaipur Foot, the pinnacle of innovation and human dignity to its clients using most advanced technologies and reaching people in far-flung areas. I am lifted by the extraordinary success for humanity."

The Federal has also reached V. Vidyavathi, secretary, Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities, on email for comment on the BMVSS. The article will be updated if a response is received.

“There is a powerful management committee in place. Value systems are in place. We believe in equality in assistance irrespective of financial standing, caste, creed, or religion. The most important lesson we must remember is to treat patients individually with respect and as human beings,” said Mehta.

He added: “We can see the transformation of patients. When they come in, their faces are sad and worried. When they leave this place, they are happy and joyful. That joy is infectious and priceless. That joy will keep BMVSS going for at least another 50 years.”