- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How artists are collaborating with local communities to bring about change in urban India

From a wall mural in Mapusa, Goa, to interventions in Cooke Town, Bengaluru, and events centred around a neighbourhood tamarind tree in Kolkata in a desperate attempt to save it, such projects show how local ownership can make a lasting impact.

Across urban India, artists are collaborating with communities to reshape public spaces. The community involvement is driven by a strong desire to reclaim public spaces through collective action. Residents view neglected public spaces not only as reminders of what has been lost but also as opportunities for renewal. By restoring these spaces, they are aiming to revive cultural heritage and...

Across urban India, artists are collaborating with communities to reshape public spaces. The community involvement is driven by a strong desire to reclaim public spaces through collective action. Residents view neglected public spaces not only as reminders of what has been lost but also as opportunities for renewal. By restoring these spaces, they are aiming to revive cultural heritage and bring about grassroots change.

“It is easier to be passionate about a distant cause than to bring change in your own locality,” says Debalina Majumder, who has spearheaded one such initiative in Kolkata. Described by some as a “labour of love”, such projects show how local ownership can bring about lasting change.

A look at three such community-collaborations, changing neighbourhoods in east, west and south India.

Mapusa Mogi, Goa

In North Goa, the ongoing Mapusa Mogi Mural project, conceived and led by muralist, visual designer, and comics artist Orijit Sen, is a labour of love. Sen has lived in Mapusa for over 25 years, and his relationship with the town finds reflection in the mural.

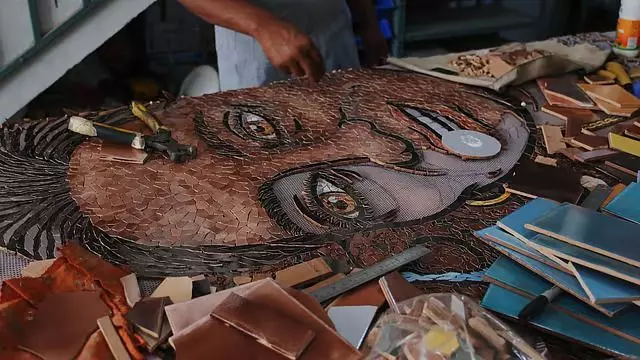

Sen has developed the mural through collaborations with local artists and researchers, envisioned as a landmark that will endure for generations. The mural is on a 100-metre long and 8-metre high wall, and is located opposite St Jerome’s Church in Mapusa market. A 7-metre centrepiece — brought to life in mosaic and ceramic by artists Shallu Sharma and Thomas Louis — has already been completed.

Also read: How an art style that flourished in 18-19th century Patna is getting a second shot at popularity

In 2013, Sen worked on the ‘Mapping Mapusa Project’, under Goa University’s Mario Miranda Chair Visiting Research Professors Programme. The initiative involved students, artists, designers and residents documenting the Mapusa market. Over time, Sen decided to create a public artwork that would both represent and be accessible to the community it depicted. The Mapusa Mogi project, which literally translates to ‘Mapusa Lover’, formally began in July 2023, after he received an art grant.

Talking about the centrepiece, Sharma says: “Sen made the design and even printed it for me to execute. It took us three months to complete it. I have always wanted to work with him and I jumped at the opportunity when Sen asked me to.”

A 7-metre centrepiece for Mapusa Mogi — designed by Orijit Sen and brought to life in mosaic and ceramic by artists Shallu Sharma and Thomas Louis — has already been completed. Photo: By special arrangement

According to Aaron Monteiro, a media consultant for Mapusa Mogi, who lives a kilometre away from the town, "Mapusa is a thriving market city where you can find everything — from fresh fruits and vegetables to ornamental plants. The town has a deep cultural significance that resonates far beyond its boundaries. People come here from all over [North Goa] to source goods.”

As part of the Mapusa Mogi initiative, a documentary and artists' team is capturing the town’s rich legacy through videos, photographs, audio and written narratives. Some of these are being shared across social media platforms, while some are being archived for later use.

“The Mapusa Mogi Mural project reflects the town's past, present, and future, from which the community can draw inspiration, document their own stories and bring about change in their own small ways. By documenting and sharing these experiences, we hope to foster a lasting connection to Mapusa’s heritage and bring about change through art,” says Aaron.

Describing the project on his website, Sen writes, "We all know the problems that Mapusa — like so many other Indian cities — is beset with. We live them and experience them everyday: pollution, filth, overcrowding, civic and infrastructure breakdowns, corrupted urban systems… We have even begun to accept the pervasive toxicity of mind, body, society and habitat as the inevitable price of chasing the chimera of economic progress... As artists, we believe that art can be a powerful way to challenge such moribund thought processes and propose fresh new perspectives."

The Warrior Who Crossed The Drain, Bengaluru

Bengaluru-based Shiva Pathak, co-founder of the arts organisation Sandbox Collective, stresses that urban intervention is art. This perspective has informed her project ‘Mori Daatidha Veera: The Warrior Who Crossed The Drain’, a metaphor for overcoming urban barriers. The project is an artistic intervention in Bengaluru’s Cooke Town and reflects the principles of tactical urbanism: low-cost, community-led interventions that reclaim public space and aim for long-term change.

The project has received a grant from the India Foundation for the Arts (IFA) in October 2024. “We invited local residents to walk around the neighbourhood,” says Pathak. They identified problem areas, such as poor pavements, unsafe crossings, and underused spaces, and suggested possible interventions. “We grouped the photos, discussed them, and each group selected sites they felt could be reactivated.”

The team worked across three sites between January 2025 and this month. They installed safety mirrors at the Davis Road-Wheeler Road Extension t‑junction, converted a discarded concrete pole into a visual landmark and created small-scale parking interventions in Hutchins Road.

Also read: How the Edam exhibition is giving ‘edam’, or space, to Kerala’s women artists

The outcomes were mixed success stories. The painted pole became a woman vegetable vendor’s hub and the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) even painted one of the crosswalks. However, the biggest lesson came from drone footage collected of the sites. It showed that people didn’t follow the designed crosswalks. “People walk intuitively, not geometrically,” says Ojas Shetty, a collaborator, “we needed to design for actual behaviour, not what we assumed theoretically”.

The team also painted a cobbler’s shop as an extension of the project. “The vendors, shop owners, the cobbler and residents all attended the project exhibition,” says Pathak. This shows that the participants were actual stakeholders.

Participants in the Cooke Town, Bengaluru, project paint a cobblers shop in the neighbourhood as part of the initiative. Photo: By special arrangement

As part of the project, participants also recorded oral histories documenting how Cooke Town’s architecture and traffic have evolved. “One interviewee, Reena Chengappa, even mapped the entire area based on the trees planted by longtime residents, illustrating deep personal connections to the local flora,” says Pathak.

Inspired by these stories, Pathak collaborated with artist Sudha Palepu, an artist who works with botanical ink, to turn excerpts from Reena’s interview about Cooke Town’s gardens into visual art. “She extracted pigments from local botanicals – the colours of Cooke Town – painted scenes from the neighbourhood and produced a series of six paintings. The work combined oral history, botanical science and visual storytelling, resonating strongly with the community.”

Athreya Chidambi, a designer and illustrator, contributed to the artwork design. “It was a slightly new experience for me. I was among those who painted the fallen concrete pole and the cobbler’s shop. What I found the most appealing was how it brought the community together, not just from Cooke Town but from different parts of Bengaluru.”

Prasun Banerjee, founder-member of the Cooke Town Residents Association, terms the concept unique. “Usually, urban intervention is about firefighting issues like garbage collection and fixing streetlights. This community-intervention project was different.” However, he also raises questions about sustainability. Keeping the mirrors clean, ensuring the paint doesn’t wear off and general cleanliness are crucial. “Such projects serve as prototypes of revitalising urban spaces for the community; it can be scaled up if there is sustained interest in it by local authorities and residents.”

Saving a heritage tamarind tree, Kolkata

In Kolkata, the determination of documentary filmmaker Debalina Majumder sparked a community movement in saving a heritage tamarind tree in Vidyasagar Colony, South Kolkata.

The tamarind tree is home to various birds and insects, provides shade to street animals, and holds historical and cultural significance for Vidyasagar Colony, says Majumder, a local. It was planted by freedom fighter Parul Mukherjee, who passed away in 2014, in her yard. For Majumder, saving the tree became a personal passion project that gained resonance with people across Kolkata.

It all started when, after Mukherjee’s death, her family sold her property to a real estate developer. The tamarind tree was on the edge of the land. “The tree is 95 per cent on Kolkata Corporation land and 5 per cent on the private premises,” says Majumder, whose own house is close by. “It is a bearer of living memory and stands as a witness to history, making it essential not only for the environment but also as a symbol of Vidyasagar Colony’s culture.”

Majumder has been documenting the tamarind tree and its biodiversity for 12 years. Music events were held on her terrace, with recordings shared on social media and YouTube.

Also read: How Hyderabad’s iconic palaces and monuments narrate a story of past architectural glory

Reflecting on Parul Mukherjee’s legacy, Majumder recalls that she had been an active member of the revolutionary group Anushilan Samiti and strengthened its women’s wing. She was arrested twice, in 1935 and in 1937, in Titagarh for conspiring against British rule. After her release, she settled in Vidyasagar Colony, an active member of the community and a lover of nature and animals.

The tamarind tree planted by late freedom fighter Parul Mukherjee has been at the centre of events organised in an attempt to save the heritage tree from being cut to make way for real estate. Photo: By special arrangement

In 2024, when other trees in the neighbourhood were cut, including an ancient mango and jamrul (wax apple) tree, to make way for real estate, efforts to save the tamarind tree began in earnest. Artists, activists, and residents were galvanised. Two three-day musical festivals, titled Tentultolaar Gaan (Tamarind Tunes), were held in December 2024 and March 2025.

Arts curator Shubham Roy Choudhury, one of the organisers of the Tentultolaar Gaan festivals, says, “sixty-seventy people attended daily. A Great Backyard Bird Count was also held, with photographs taken and drawings made.”

Majumder’s documentary film Jilipibalar Bondhura (Friends of Jilipibala), released in 2025, centres on the tamarind tree and depicts a child’s relationship with the natural environment around her. There is beauty in how the child learns about the tree’s biodiversity, but it is interrupted by the grating sight and sound of saws piercing through tree trunks.

The first petition to save the tree was submitted in 2024 to mayor Firhad Hakim and the Forest Department, with a copy sent to Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee. “It was signed by 30-40 ward residents,” explains Samata Biswas, the producer of Jilipibalar Bondhura and assistant professor at the Sanskrit College and University, Kolkata.

A wider signature campaign was conducted in 2025. “We gathered close to 5,000 both online and offline,” Biswas adds.

According to the campaigners to save the tree, the Forest Department has given a verbal assurance that the tree won’t be cut.

Anyone wishing to save a tree can call the local police, the Kolkata Corporation (KMC), and the Forest Department, says Majumder, but deep commitment is essential . But through sustained effort, the filmmaker and the community in Kolkata have shown that change is possible.