- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How the Edam exhibition is giving ‘edam’, or space, to Kerala’s women artists

A part of the Kochi Muziris Biennale, Edam showcases the art of Malayalis from all over. On display at the ongoing 2025-26 show are the works of 36 artists. The Federal spoke to a few of the women artists about their works and how they have articulated their angst in their art.

Aishwarya Suresh was very sure that 'Edam' — a part of the Kochi Muziris Biennale, showcasing the artistic works of Malayalis from all over — has to feel like home. "The art must not feel alien, it must be warm,” explains the textile-based artist and educator, who has curated the ongoing Edam show along with KM Madhusudhanan, an inter-disciplinary artist and filmmaker.Together, they...

Aishwarya Suresh was very sure that 'Edam' — a part of the Kochi Muziris Biennale, showcasing the artistic works of Malayalis from all over — has to feel like home. "The art must not feel alien, it must be warm,” explains the textile-based artist and educator, who has curated the ongoing Edam show along with KM Madhusudhanan, an inter-disciplinary artist and filmmaker.

Together, they have chosen 36 artists for this year’s exhibition. On display are the works of both male and female artists — from across generations, the oldest being that of a 63-year-old, and disciplines.

Elaborating on the women artists, Suresh says, “Both Madhusudanan and I also consciously tried to avoid that kind of art which stereotyped women; [showing] home, children, family as their only burdens. We are not negating its value, but Edam needed something more."

Which is why she chose Priti Vadakkath, Indu Antony, Nithya AS and Devika Sundar, to name a few of the women artists featured in Edam 2025-26.

"All these women are undergoing a certain struggle in their lives, and their work is reflective of what their life is right now."

Curator Aishwarya Suresh was very sure that Edam has to feel like home. For the women artists, she wanted to avoid works which stereotyped women; showing "home, children, family as their only burdens". Photo: By special arrangement

Unlike most male artists at the exhibition, whose paintings can hardly be called 'personal', these women have articulated their angst into their art.

So if Priti's Grasslands is about her standing at the threshold of building a new life for her son, Indu's exhibit is proof of her compulsive hoarding. The courage of Devika to paint over the debilitated parts of her body and the trauma that Nithya — the youngest of the lot at just 25, financing her own education because her family cannot accept her choice of profession — has about hair.

And if Edam (meaning space in Malayalam) cannot have an edam for these women's artwork, how else will the world know that they exist? Because women artists are often paid less and represented less in the art world.

Despite being an artist of considerable repute, even Aishwarya had concerns about putting herself out there. Women artists need to break out of it — the fear of being judged because of what they draw.

"As a woman curator, I am not going to be spared. What hope is there then for those who have bared it all?"

Aspiring young women find it an ordeal to convince their own family, let alone build a career as an artist. And that rare breed, who are successful, live alone.

Aishwarya recalls her vain attempts back in July 2025 to convince a 50-year-old woman artist to participate in the Edam exhibition, after seeing her work in her studio; to start composing her painting exhibits for the show. "She was all excited, but a week later, she stopped taking my calls. The day she finally picked up, she said she didn't have the money. The only income was the money she got from teaching painting classes. I told her that I could get her financial help," remembers Aishwarya. But the artist just wouldn't commit despite relentless cajoling from both the curators. "[The] Fact was that her husband, an out-of-work artist himself, just couldn't accept the recognition that came her way and forbade her from participating."

Another struggle of curating was in training the fresh graduates from art colleges to speak about themselves and their work. "They lacked the language and the confidence to articulate their work in words. I had to sit with them and start from zero."

The efforts have paid off.

On till 31 March, alongside the main Kochi Muziris Biennale, Edam 2025-26 is a huge hit. Call it clannishness or a consequence of Mallu jingoism, the Edam, which started in 2022, does make you feel you're home. And you want to stay on.

The Federal spoke to a few of the women artists showing at Edam — new and veteran, classic and contemporary — about their work.

Also read: How women directors are claiming their space in Kannada cinema, blending arthouse with mainstream

Priti Vadakkath

The first time you see Priti Vadakath’s painting, The Grasslands, you take two steps forward. And when you realise what the subject is, you involuntarily step back. Because at first, you’re so awed by the sheer gigantic size of the canvas that you expect it to show something abstract. Then at close range, you realise it is just grass — tall and thin, yellow and brown and green, acres and acres of it. And that’s when it hits you that this painting is not to be 'viewed' from a spot; it needs you to walk through. Spanning 21 feet across the wall, that is no small feat.

Priti’s artwork was always botanical. Where in the past she drew botanical plants displayed in single rectangular frames, this time she chose to widen her canvas and choose a subject that is a ‘menace’ to farming anywhere in the world.

“We had to move to the High Ranges [in Kerala, part of the Western Ghats] after my son turned 18. His autism was on the severe end of the spectrum, he is non-verbal. Once an autistic child becomes an adult legally, his options for formal therapy are zero. Parents become the sole therapists. We chose to create a new life atop the mountain ranges in Central Kerala, at Swargamedu, in Idukki district.

The grasslands are the only vegetation in that place. “We had to clear the area of it to build our house and start a regenerative farm. The easiest option was to burn it without causing a forest fire, and as we were doing that I felt guilty. We were committing a violent act against nature. That got me thinking of the role of grasslands in the ecosystem. Am I doing good or damage here?”

People consider grass to be weeds, something to be eradicated, a parasite that hogs the soil in which something meaningful can be grown. “But I realised that these grasslands are fast growers, dynamic and strong. And even when they were burnt, they could not be destroyed completely,” says the artist.

Spanning 21 feet across the wall, Priti Vadakath’s The Grasslands is magnificent — in visual imagery, in size and in depth. As you walk through, you can ‘see’ the wind and how the grass is getting plastered in its direction. Photo: By special arrangement

For Preeti, that was symbolic. “The resilient nature of the grass inspired me greatly. It resonated with me, my determination to create a new life for my son.”

Translating that into art, however, was not easy. “It took me three years to complete this project. I started with sketching a few species of this type — some medicinal, some wild. I took plenty of photographs and as I went through them, I was astonished by the visuals. How the grass changes its colour according to the topography, the light, and the seasons. I slowly started drawing them. The move from single rectangular frames to a wall-to-wall canvas was a conscious one. One, because the subject demanded it. And two, the new house allowed me to have a massive studio.”

Using a scaffolding and a ladder to help with the height, and since every stroke had to be perfect in one swipe, Priti would paint very close to the canvas, then get down, walk away, take photographs, check them for proportion etc, and then get back on the ladder again. It was paint, walk, check — repeat on a loop.

The canvas was stretched over a specially designed wooden frame. After completion, the whole canvas had to be removed, the stretchers dismantled for transportation, and restretched on site for the exhibition.

Logistics never worried her. As she says, these days anything can be transported anywhere.

The ‘Grassland’ is magnificent — in visual imagery, in size and in depth. As you walk through, you can ‘see’ the wind and how the grass is getting plastered in its direction. As you look closer, you can see that the grass becomes abstract. “Each blade is a different gradation of the colour. Basically, what I’ve done is strokes — single swipes, with no room for repetition.” You’ve got to get it right the first time, the only time.

Grasslands is showing at The Garden Convention Centre, Fort Kochi.

Indu Antony

Artist Indu Antony’s pre-occupation with hair has created one of the most astounding art installations at Edam. Indu has been collecting hair for more than 10 years. It may not be her own hair, not even a human’s. “I collect it in jars and place it all around my house, even on the kitchen shelves.” For Indu, hair is associated with memory. “I’m one of those fortunate people who have a long and sharp memory. I don’t forget that easily. Everything that happens around me stays with me. Hair is the one thing that best serves my memory.”

Faces may fade, but hair will always remain.

For Artist Indu Antony hair is associated with memory. Her pre-occupation with hair has created one of the most astounding art installations at Edam. Photo: By special arrangement

Her art exhibit Evar (these people) will prove just that.

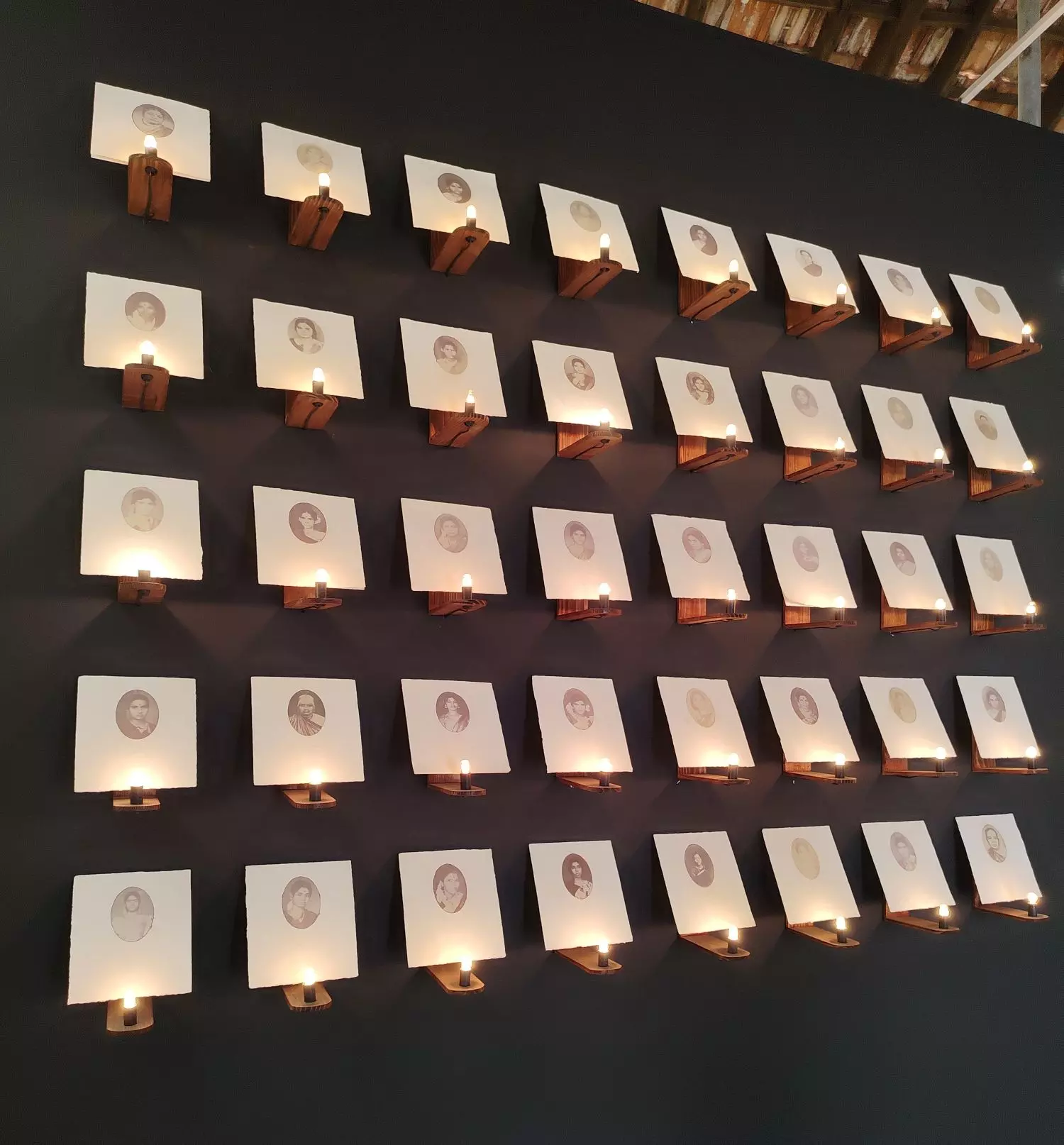

Evar is a collection of 40 photographs of random women picked up from dust bins and old cellars into which they were thrown whenever these women moved from house to house. “I have 400 such photographs at home. They became part of my material library, the source for my art.”

Around each photo, Indu has stitched strands of her own hair to line its oval borders. The photos are pasted on to salted paper prints – an analog methodology for preserving archival photographs. These were then mounted like dots on a wall, in rows of eight photographs each, each print tilted on a wooden keg with a lighted bulb at its tip. “The lamp is a symbol of reverence. Just as we place a light in front of those we hold close to our hearts, these bulbs are my ode to these women.”

A lot of people tell Indu that her artwork is brilliant, but if only it weren’t for the hair, they would’ve bought it. “But I don’t mind. I know people find hair disgusting.” For Indu, however, it is the only undecomposed souvenir of a person.

Her other installation at Edam centres on a pair of handmade gloves crafted with her own hair with the words — enne pidikko (will you hold me?) — stitched using the same strands. “That was to show the skin-hunger that I experienced during the Covid years. I’ve been living on my own for the last 20 years. It was always lonely but the pandemic made it painful. I craved for touch. In my family, we never touched. That distance caused me a lot of unrest within. Physical touch is a unique thing. And through this installation, I was crying — please hold me.” But the gloves are placed in a glass box, meaning that the cry is never responded to. “By sealing the gloves within glass, the work holds this tension between desire and separation.”

Evar (these people) is a collection of 40 photographs of women. Around each photo, Indu has stitched strands of her own hair. The photos are mounted like dots on a wall, with a lighted bulb at its tip. Photo: By special arrangement

Language is also a key factor in her works — ponnupole (like gold), aarodum parayalleda (don't tell anyone), enne pidikko and evar.

“For me, Malayalam is like a warm embrace”, says Indu, who speaks eight languages. “When I’m in a foreign country, and I feel so alone, suddenly I hear conversations in Malayalam, and I become instantly happy. I feel like going up to those people and hugging them. And then, the ubiquitous question — naattilevideya? [where is your native place?]”.

Evar and Enne Pidikkoo are showing at the Armaan Collective.

Also read: How an art style that flourished in 18-19th century Patna is getting a second shot at popularity

Nithya AS

If hair is akin to a stitching thread for Indu, it is symbolic of prejudices, superstitions and vanity for Nithya. A weapon for men, a lucrative tool for professionals, a source of familial bonding — the list is endless. In short, Nithya cannot think of hair without reliving some kind of trauma.

“Watching my mother and my grandmother in both their open and closed spaces, I saw that hair for them meant a myriad of things.” Nithya’s mother had beautiful knee-length hair. When she began to consume fertility pills, her luxurious mane started to fall off. She would apparently collect the fallen hair, ball it up, and lament over the loss. “Today, I realise it must have been her postpartum depression, but at that time, nobody made an attempt to understand it.” Nithya says her dad, instead of consoling, blamed her mom even more. “One day, my brothers and I returned from school and saw that she had shaved her head.” Stunned and speechless, Nithya’s life changed completely. She started having nightmares about a hair monster that chased her relentlessly. Even when awake, she started feeling a haunted presence of hair hovering around her room and the house.

If hair is akin to a stitching thread for Indu, it is symbolic of prejudices, superstitions and vanity for Nithya AS. She cannot think of hair without reliving some kind of trauma. Photo: By special arrangement

Later, as a teenager who lived almost eight years in various hostels, she started looking at hair as something to be petted. “I saw that people showed their affection by ruffling one's hair. I noticed friendships being forged when one washes another’s hair. I started recalling how my mother used to brush my hair gently and lovingly.”

At the same time, she also started noticing that girls were now curling their hair when traditionally, curly hair was looked down upon as ‘difficult and unruly’, that women, including her mother, were going through great lengths to get rid of facial hair and body hair — these observations around hair, says Nithya, is the inspiration for her paintings at Edam.

In Weightless Burden, using acrylics on canvas, Nithya has composed an everyday scene of her mother’s self-care. It also shows a young Nithya opening a door into a corridor and looking up at a floating debris of hair. Photo: By special arrangement

In Weightless Burden, using acrylics on canvas, she has composed an everyday scene of her mother’s focused self-care within her safe but open domestic space. It also shows a young Nithya opening the door of her bedroom into a corridor and looking up at a floating debris of hair, round-eyed in trepidation. The setting — the wash basin with its array of cosmetic bottles, the checkered floor, the unmade bed — are brilliant in its simplicity and realism.

“First, I get my friends to pose in a particular setting and likewise, I ask them to take my poses. I use props in my photographs to render a certain meaning. I dig into my memory and past narratives to create these compositions, but sometimes, I change my architectural spaces so that people can relate to them better.” The drawing comes later.

Of the other two untitled paintings, one shows a girl getting her hair washed by professional hands in a salon setting, while the second shows the interiors of a bathroom where one girl pushes the head of another bruise-ridden, bare-backed girl under a tap, evidently helping to wash her hair because she is unable to do it on her own.

Why? Did the girl go through some unspeakable trauma?

Such is the stark realism and strong use of allegory that the images stay with you long after you have left the venue.

Nithya AS's paintings are showing at the Garden Convention Centre.

Devika Sundar

Devika speaks with her hands. Soft-spoken to a fault, her hands are forever in motion — graceful, lithe and fluid — articulating her innermost feelings in ways that words never can. Because if there’s anyone who understands the relevance of limbs — physically, anatomically, artistically — it is Devika Sundar.

“It was during my art school graduation in New York that the pain first hit." That was in 2009. "It started slowly from the neck and shoulders and eventually it was everywhere. Doctors couldn’t find the cause and my condition remained undiagnosed for the longest time, misdiagnosed, rather.” Prior to that, Devika’s art comprised drawings and collages that talked of memories, people and images from her daily life. “I was a reserved child and art was my go-to place.”

The pain was chronic and relentless. She became ‘immobilised’ as an artist. On bedrest for months together, she ‘struggled to negotiate her relationship with art’.

It was only in 2016 that she was diagnosed with fibromyalgia, an invisible chronic pain that affects the entire nervous system. The bottom line — “it will not surface on conventional testing”.

Ergo, the Lightboxes.

When her thesis mentor discussed the ‘ideas around invisibility’ as a theme for an art project, she recalled her medical scans. “The cohort behind the project spoke about invisibility as a failure, unlike success, it is not articulated well. My medical scans did not articulate my illness at all.”

So, she pulled out eight years of her medical scans. For more than the two years that she went through unexplained pain, these scans showed nothing. “When you’re going through something invisible, hidden and unexplained, there’s a lot of stigma.” She also realised that hospital spaces are patriarchal. Women with unexplained health issues are forced to go through multiple MRIs, CT scans, X-rays, but when nothing conclusive shows up, they’re told that it is owing to stress or hormones.

“I looked at my scans as objects of failure. I scanned it, traced it out, marked on it with my white pen. I played around its exposure — searching for the muffled layers beneath the scans; its language — the clinical data belied name, age, gender; its colours, juxtaposing it with colours of my own in order to remove the dark sterility of these scans. The art I applied to these scans was very intuitive; my attempt was to subvert it with my own language.”

Devika Sundar has pulled out eight years of her medical scans to use it for her work, Lightboxes. The scans are stretched over illuminated shoe-sized boxes, giving the clinical images beauty and interpretation. Photo: By special arrangement

The scans are stretched over illuminated shoe-sized boxes, giving the cold clinical images a beauty and interpretation of their own. There’s no room for doubt that it is what it is. But what it also conveys is the humanity of the artist — her quiet resilience amidst her conflicted relationship with her scans.

Through the Lightboxes, Devika says she was "able to come to terms with her own sense of discourse and dysphoria".

“When people ask me if I’m trying to make my pain the focal point of my work, I tell them NO. This is my way of negotiating with my pain, and there is no better medium than art. It makes you negotiate better.”

Lightboxes is featured at Armaan Collective.