- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

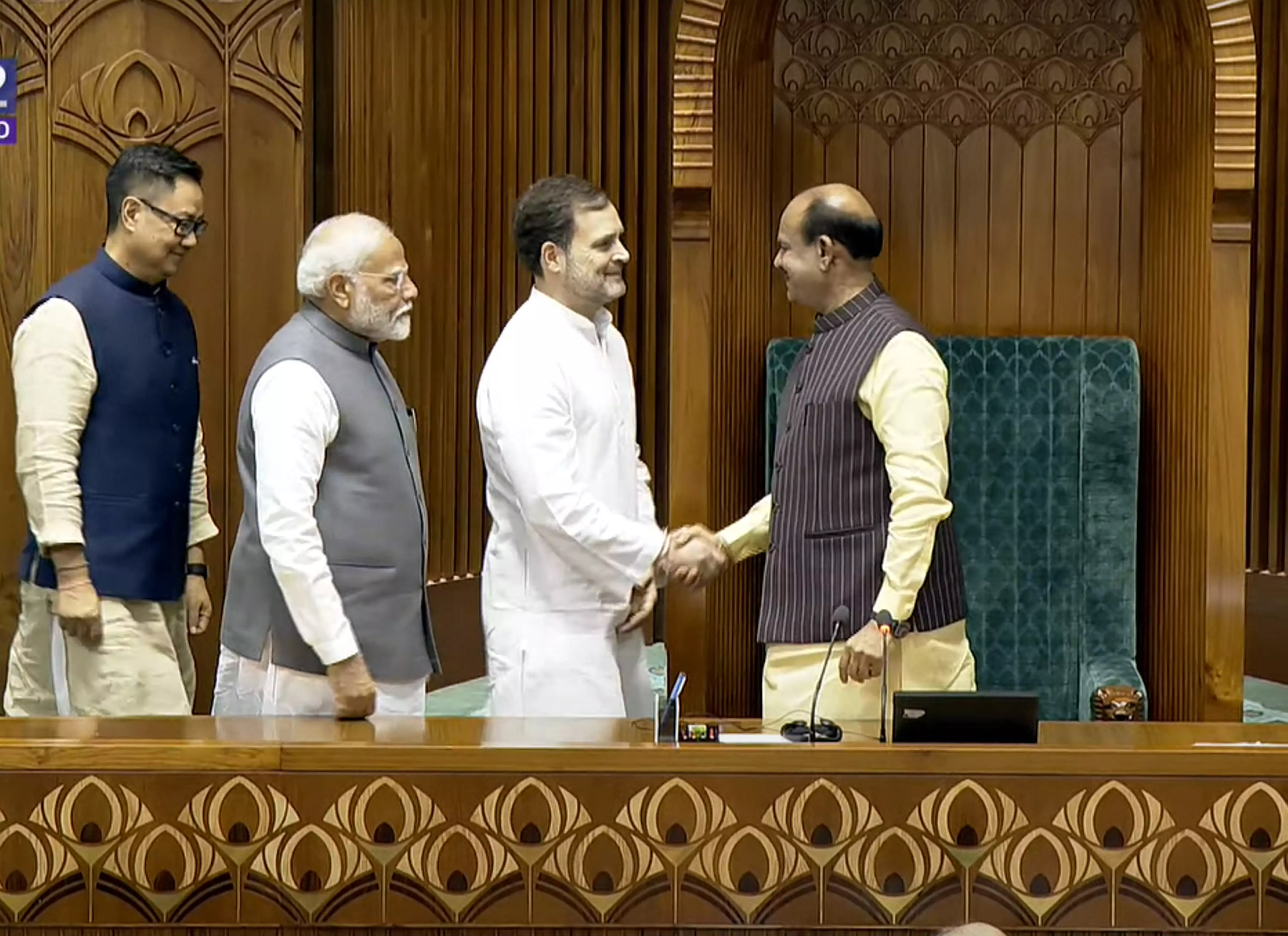

Congress MP Rahul Gandhi congratulates Om Birla (right) after he was elected the Lok Sabha Speaker on Wednesday (June 26) as Prime Minister Narendra Modi (2nd left) and Union Minister Kiren Rijiju look on. PTI

The election for the Speaker has been a rarity in India’s parliamentary democracy. Up until Wednesday’s vote, such an election had been held only thrice in the Lok Sabha

The election of the Speaker for the 18th Lok Sabha could have been so much more than a mere symbolic gesture of muscle flexing against the regime by a resurgent Opposition. What the Opposition turned it into, however, was a poor joke on Parliament and, more importantly, on those who voted for the INDIA bloc hoping, if not for a change of regime then, at the very least, for a strong Opposition that wouldn’t just bare its teeth but also bite when it matters.

The election for the Speaker has been a rarity in India’s parliamentary democracy. Up until Wednesday’s vote, such an election had been held only thrice in the Lok Sabha – in 1952 when Congress’s GV Mavalankar trounced Peasants and Workers Party of India leader SS More, in 1967 when the Opposition backed independent MP Tenneti Viswanatham was defeated by Congress stalwart Neelam Sanjiva Reddy and in 1976 when Congress’s BR Bhagat triumphed against Jana Sangh’s Jagannath Joshi.

Birla vs Suresh

What was common to all of these three elections was that the Opposition of the day, despite being nowhere as robust in its numerical strength as the INDIA bloc is today, not only fielded a candidate to register its protest against the then government on one matter or the other but also forced a division of votes. In 1952, Mavalankar secured 394 votes of Lok Sabha MPs against More’s 55 votes while Reddy, in 1967, got 278 votes against Viswanatham’s 207 votes. In 1976, the election that took place to elect a new Speaker within a year of Indira Gandhi’s imposition of Emergency saw her party candidate Bhagat get 344 votes against Joshi’s 58 votes.

Wednesday’s vote in the Lok Sabha was necessitated because the INDIA bloc, like the Opposition back in 1952, failed to secure an assurance from the government of getting the Lok Sabha Deputy Speaker’s post for one of its own flock. The Congress declared that its seniormost MP and Dalit leader, K. Suresh, would challenge NDA nominee and BJP leader Om Birla, who had also served as Speaker in the 17th Lok Sabha, in the election.

The just concluded Lok Sabha polls gave the BJP-led NDA a seemingly uncomfortable majority of just 293 seats against the INDIA bloc’s 234 MPs. In the aftermath of that close result, the INDIA bloc has been making much noise about its conviction to fight the Narendra Modi government with renewed zeal. The Speaker’s election afforded the Opposition its first post-poll chance of a show of strength and resolve.

Birla declared winner by voice vote

But then, as soon as the motion moved by Modi and seconded by Rajnath Singh in favour of Om Birla’s candidature was declared passed by Speaker Pro-Tem, Bhartruhari Mahtab, all expectations of a combative Opposition giving the government no quarter rolled steeply downhill.

Mahtab declared Birla victorious based on a voice vote. As a puzzled Rajeev Ranjan Singh ‘Lalan’, the Union Panchayati Raj minister wondered about the division of votes, the Speaker Pro-Tem responded that the division had not been sought. What followed was an image that is likely to haunt Rahul Gandhi, the newly appointed Leader of Opposition in the Lok Sabha, and others in the Opposition ranks for the next five years.

Rahul walked across from his bench to join Modi in congratulating Birla on his victory and then, along with the PM and Parliamentary Affairs minister Kiren Rijiju, ushered Birla to his high chair, smiling all the way.

Rahul's speech lacks substance

But this wasn’t the end of the dramatic anti-climax. His congratulatory speech, displaying uncharacteristic restraint, dwelled mostly in the abstract instead of substance. He urged the Speaker, who in his previous stint in the same office between 2019 and 2024, suspended the single-largest number of MPs – all of 100 – from the House in a matter of days during Parliament’s 2023 winter session, to ensure that “the voice of the Opposition is allowed to be represented in this House”.

Asserting that he was “confident that you (Birla) will allow us to represent our voice”, Rahul said that the “idea that you can run the House efficiently by silencing the voice of the Opposition is a non-democratic idea and this (Lok Sabha) election has shown that the people of India expect the Opposition to defend the Constitution...”

A number of Opposition leaders who spoke after Rahul – Samajwadi Party’s Akhilesh Yadav, Supriya Sule of the NCP (SP), Trinamool Congress’s Sudip Bandopadhyay – were vastly more caustic in welcoming Birla back to the Speaker’s high office. All of them reminded him, directly or in scarcely veiled terms, that his past stint as Speaker was characterised by all that which isn’t kosher in parliamentary democracy. The most poignant intervention, arguably, was by Ruhullah Mehdi, a first term National Conference MP from J&K’s Srinagar, who pointedly told Birla that “you wouldn’t be remembered for hosting the P-20 but for when a Muslim MP in this House was called a terrorist by another MP and... you did nothing”.

The bottomline, however, remained that none in the Opposition, despite the palpable trust deficit in Birla’s ability to discharge his constitutional duties with impartiality, had, moments earlier, taken their collective fight against the government’s undermining of Parliament to its logical end. When the motion to elect the Speaker was put to vote, none in the Opposition demanded a division of votes.

Why no division of votes

A few muffled voices that were heard demanding the division came much after the result of the voice vote had already been declared. Such voices now were relevant only for a political powwow, which was seen outside Parliament with Trinamool MPs, who until a day earlier were more hurt at the Congress’s decision to field Suresh than the BJP’s choice of Birla, alleging that a division was sought but not granted. To make matters worse, Jairam Ramesh, the Congress’s verbose communications chief, declared on X that “INDIA parties could have insisted on division; they did not do so... because they wanted a spirit of consensus and cooperation to prevail”.

On his part, Birla served the Opposition, particularly the Congress, their just desserts minutes after the congratulatory messages ended. He broke into a nearly seven-minute long soliloquy condemning the late Indira Gandhi, individually, and the Congress party, as a whole, for the “dark period” of the Emergency. The statement sent an already unstable INDIA bloc into disarray with Congress MPs trooping into the Well of the House in protest against Birla’s “divisive statement” while MPs from the Trinamool, Samajwadi Party and other INDIA constituents sat pretty.

Readers may wonder why so much is being made out of the Opposition’s failure in insisting on a division of votes or, indeed, why Birla is being singled out for ridicule. The answers stare one in the face.

It was always known that the Opposition did not have the numbers to ensure Suresh’s victory. The fight was, thus, symbolic. But, what symbolism, other than that of a losing battle, did the Opposition actually achieve by fielding its candidate and that too a Dalit?

17th Lok Sabha, least productive since independence

Did the Opposition succeed in telling the country exactly how many MPs, especially those from a party that made much song and dance about getting a Dalit elected as President of India in 2017 and a tribal woman elected to that office in 2022, voted against the only other Dalit since GMC Balayogi (1998 to 2002) and Meira Kumar (2009 to 2014) who could have become the Lok Sabha Speaker? No. If anything, the election showed that the Opposition, particularly the Congress, lacked the conviction to demonstrate an anti-Dalit streak in the NDA and, in doing so, made its own Dalit leader K. Suresh a pawn in a losing battle.

Did the Opposition, which has been claiming that the Modi government enjoys an unstable majority, succeed in showcasing any cracks in the 293-member NDA squad? No. Was the Opposition, given the BJP’s proven ability to break the ranks of its rivals, scared that a division of votes could prove counter-productive and show an increased number for the NDA or a reduced tally of the INDIA bloc? Perhaps, yes.

So besides a victory for Birla and the NDA government, what did the Opposition really achieve by forcing a sham contest? It doesn’t take much to recognise Birla as one of the most controversial, if not singularly disgraceful, leaders to have been installed on the hallowed chair of the Lok Sabha Speaker. His record speaks for itself.

The 17th Lok Sabha, of which Birla was first elected Speaker, was the least productive Lok Sabha since independence. Its average annual sittings came to an all time low of a mere 55 days, lower than even the paltry 66 days of Modi’s first term in power, when Sumitra Mahajan was the Speaker, or the 71 days during the UPA-II regime of Dr Manmohan Singh, when Meira Kumar was the Speaker.

Mass suspension of MPs

As Speaker of the 17th Lok Sabha, Birla presided over a swift erosion of nearly all parliamentary conventions. The Modi government got away with keeping the Deputy Speaker’s chair, a constitutional post like the Speaker’s, empty for all five years.

Only four of the 15 sessions of the 16th Lok Sabha (including the special session convened in September 2023) spent more than 35 hours discussing legislative business. Of the 221 Bills passed by the Lok Sabha, nearly 73 (one-third) were debated for less than an hour, 28 others for a maximum of two hours and only 66 for three hours or more. Only 16 per cent of the Bills introduced in the 17th Lok Sabha were referred to various parliamentary committees for further scrutiny; a sharp fall from even the worryingly small percentage of 28 per cent during Modi’s first government and a far cry from the 60 per cent and 71 per cent from the UPA-I and UPA-II days, respectively.

If this wasn’t enough, there was the mass suspension of MPs too – as many as 100 within a few days in the winter session of 2023 and a total of 115 during the course of the 17th Lok Sabha. This empirical data aside, there was also the larger question of whether Birla displayed even a modicum of fairness and bipartisanship in conducting the business of the Lok Sabha.

Missed opportunity for INDIA bloc

Almost all Opposition MPs, while congratulating Birla on his return as the Lok Sabha Speaker, expressed hope that his second coming would be marked by fairness. What gave the Opposition such an impression, other than the exaggerated self-belief in its increased bench strength, is anybody’s guess.

The Opposition has started its innings in the 18th Lok Sabha with a missed opportunity. The Speaker’s election only shows that the INDIA bloc still hopes to fight a brazenly defiant and autocratic government – and its committed figureheads in different institutions, including the country’s largest Panchayat – with nothing more than half measures.

The Opposition's 55 MPs who voted against Mavalankar in 1952 or the 58 MPs who voted against Bhagat in 1976 and even the 207 MPs who voted against Reddy in 1967 were fewer in number than the INDIA bloc's 237 MPs but they made themselves count in the Lok Sabha for the parliamentary and political principles they stood for. The INDIA bloc had a chance to demonstrate that Birla, as Speaker of the Lok Sabha of the world's largest democracy, did not enjoy the confidence of almost half of the MPs he was set to preside over for the next five years but it failed miserably in doing so.