- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

As New Delhi courts Brussels, unequal market access, rigid EU rules, blocked mobility raise doubts over who truly benefits from much-touted trade agreement

As India marks its 77th Republic Day, the Narendra Modi government appears to be ushering in a new chapter of labour export — one eerily reminiscent of the colonial-era “indentured” labour system imposed by the British Raj nearly two centuries ago.

“India is signing trade and mobility agreements with several countries,” Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared. “These trade agreements are bringing new opportunities for the youth of the nation,” he added, just days before the anticipated signing of the India-European Union free trade agreement.

'Mother of all deals'

Yet, this optimism clashes with reality. Despite Europe’s tightening restrictions on short-term skilled service providers, hopes are being raised that Indian graduates — whose numbers swell by the day — will find new avenues abroad through these deals.

The proposed pact with the 27-member EU is being hailed as the “mother of all deals”. But details remain scarce: no specifics on tariff reductions or non-tariff barriers have been disclosed, and negotiations continue under a veil of opacity.

Also read: As India, EU near free-trade agreement, here’s what’s at stake

India may now be the world’s fourth-largest economy with a $4 trillion GDP and the largest population, but the EU remains the planet’s dominant economic bloc, responsible for nearly half of global trade and generating $16 trillion in annual exports.

Why India risks the short end of a EU trade deal

♦ Limited tariff gains amid crowded EU trade landscape

♦ Stringent regulatory and sanitary & phytosanitary barriers

♦ Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism raising export costs

♦ Restricted labour mobility and services visas

♦ EU pressure on India’s government procurement market

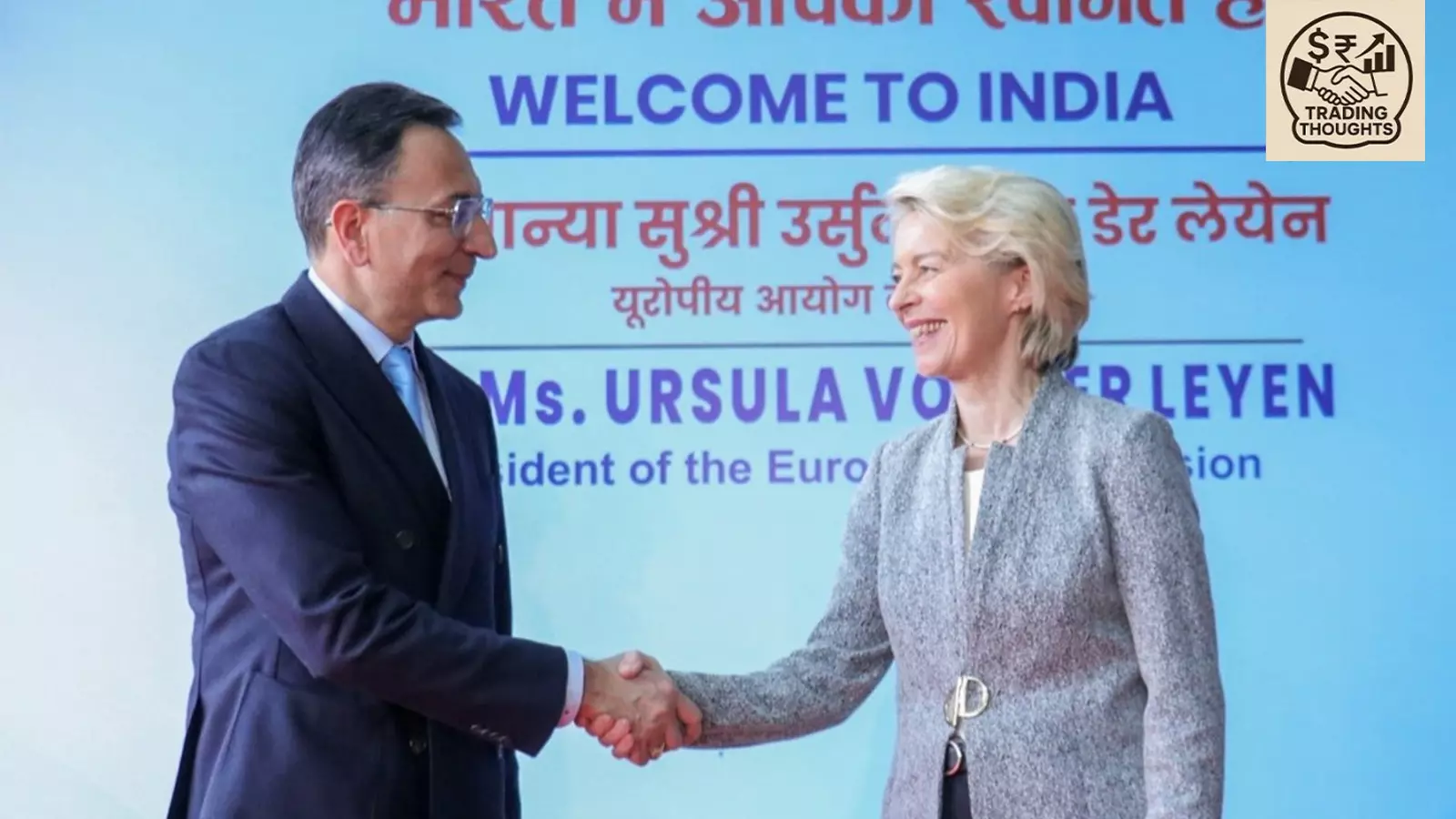

Little wonder, then, that European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen boasts: “Europe will choose the world, and the world is ready to choose Europe.”

Weakened EU

Earlier this month, the EU concluded a landmark trade deal with Mercosur—the South American bloc comprising Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, Brazil, and Bolivia—after 25 years of talks. Whether it survives ratification by the European Parliament remains uncertain, given fierce opposition from powerful farm lobbies in France, Ireland, Belgium and elsewhere.

Meanwhile, developing nations like Vietnam and even Bangladesh have already secured comprehensive free trade agreements (FTAs) with the EU, capturing significant market shares in sectors like textiles. India risks arriving late to a crowded table.

The EU itself appears weakened. Once a formidable negotiator—as during the Uruguay Round that birthed the WTO, when it dominated agriculture talks and even stalled negotiations—it now seems diminished. Last year, at the Turnberry golf club in Scotland, Brussels reportedly capitulated to Donald Trump’s America, agreeing to zero tariffs on a range of US farm and industrial goods in exchange for a mere 15 per cent tariff on EU exports to the US.

The backlash was swift: European parliamentarians cried foul, and the deal now hangs in limbo. Against this backdrop, what can India realistically expect from the “mother of all trade deals”?

What India can expect?

Even if the EU grants meaningful market access—say, by lowering tariffs on Indian textiles or agricultural products—the playing field is far from level. The EU has already woven a dense web of trade pacts, with more in the pipeline: the EU–Indonesia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, the Investment Protection Agreement, and the EU–Mexico deal, among others. Dislodging entrenched exporters will be an uphill battle.

Also read: EU unveils new strategic agenda to deepen ties with India

Then there are the EU’s notorious regulatory barriers. Nearly half of its WTO trade disputes stem from sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures and technical barriers to trade. As the New Delhi-based Global Trade Research Initiative (GTRI) noted recently, Indian exports face “regulatory delays in pharmaceutical approvals, stringent SPS rules affecting food and agricultural exports such as buffalo meat, and complex testing, certification and conformity-assessment requirements.”

High-value Indian farm goods—including basmati rice, spices, and tea—are frequently rejected or subjected to intensified inspections due to the EU’s drastically lowered pesticide residue limits. Marine exports trigger higher sampling rates over antibiotic concerns, GTRI added.

CBAM crackdowns

Over the past two years, the EU has drawn sharp criticism for unilateral non-tariff measures like the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

Recall that leaders of the expanded BRICS bloc recently rejected “unilateral, punitive and discriminatory protectionist measures, that are not in line with international law, under the pretext of environmental concerns, such as unilateral and discriminatory CBAMs.” They further opposed “unilateral measures introduced under the pretext of climate and environmental concerns” and pledged greater coordination on these issues.

“Europe will choose the world, and the world is ready to choose Europe.” - European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen

Indian steel and other industrial exports could face steep costs under CBAM. “Tariff liberalisation alone will not deliver proportional export gains unless accompanied by regulatory cooperation, faster approvals and mutual recognition in any trade deal with the EU,” warned GTRI founder Ajay Srivastava.

Also read: What did Modi, EU leaders discuss?: Ending Ukraine war, sealing FTA deal by Dec

While the EU has granted carveouts to American goods, it’s unlikely to extend the same courtesy to India—doing so would erode its leverage in other negotiations.

Services and labour mobility

Beyond goods, services face their own roadblocks. The EU restricts remote digital service delivery and often forces Indian firms to establish local operations. India is also seeking recognition as a “data-secure” country under the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)—a status that would ease cross-border data flows.

Without it, Indian firms face higher compliance costs than competitors from Japan or South Korea, experts have noted.

Crucially, labour mobility remains a mirage. EU member states staunchly oppose short-term services visas, framing them as immigration threats, even though such movement is permitted under existing, albeit fading, liberal trade rules.

Access to Indian market

Meanwhile, the EU is pushing hard for access to India’s $600 billion government procurement market, including contracts awarded by the Union government and public sector undertakings.

Ironically, Brussels now seeks to reroute exports of automobiles—especially cars—and engineering goods like high-speed electric trains away from China and toward India.

EU has already woven a dense web of trade pacts, with more in the pipeline, like those with Indonesia, Mexico, and so on. Dislodging entrenched exporters will be an uphill battle for India.

This pivot stems from China’s rapid advances in electric vehicles and renewable technologies—solar panels, wind turbines—areas where the EU once held sway. With its market share evaporating, the EU sees India as a ready alternative.

But at what cost?

If Siraj-ud-Daula—the 18th-century Nawab who fought valiantly to deny the East India Company monopoly rights—were alive today, he might warn Modi not to be seduced by Brussels’ lofty promises.

In the end, India seems increasingly resigned to Thucydides’ timeless axiom: the strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must. Once aspiring to Vishwaguru (world teacher) status, India now appears reconciled to a more humbling role: becoming the world’s largest supplier of indentured labour.

(The Federal seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. The information, ideas or opinions in the articles are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Federal.)