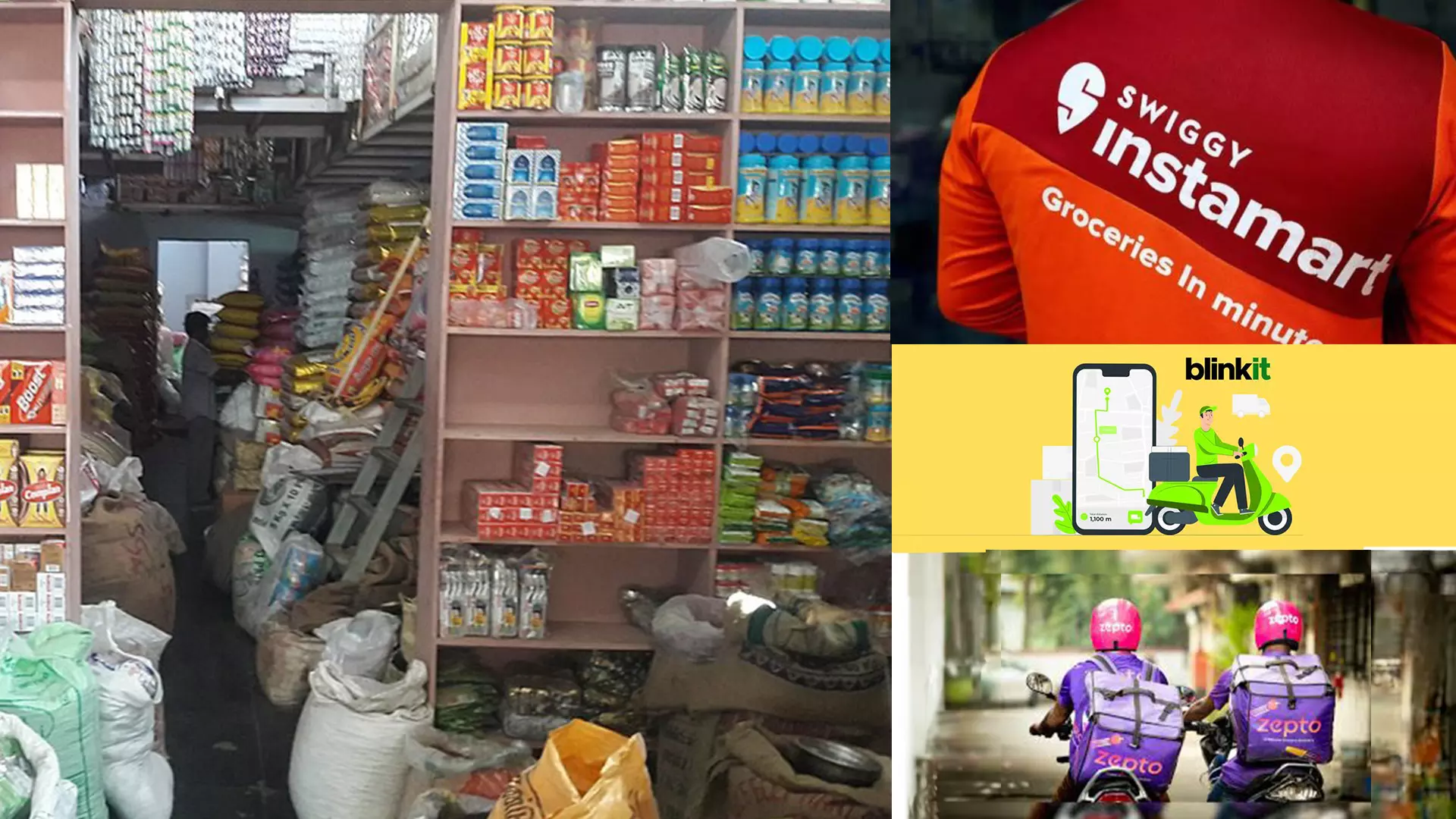

Q-commerce is strangling kiranas, but is its growth model tenable?

Quick commerce is a high-cost, thin-margin business; some of its 'victims', the kiranas, are fighting back, embracing digital strategies and enhancing customer service

At last count, nearly 2 lakh neighbourhood kirana stores (small outlets selling groceries, FMCG goods, etc) across the country have closed down, thanks to quick commerce (Q-commerce), which has a stranglehold over how India shops today.

It is not just these mom-and-pop stores that are running out of business; even supermarkets and hypermarkets are in danger of losing out to Q-commerce.

For example, Avenue Supermarkets, which runs a national chain of supermarkets and hypermarkets under the DMart brand, faces an existential crisis.

“While QC (convenience-focused) formats are differently positioned, there are initial signs of DMART ceding market share to these players (esp. in large metros). This trend needs closer monitoring,” HDFC Securities Research said in its October 10 report.

Rapid rise

As urban consumers increasingly embrace platforms such as Blinkit, Zepto and Instamart, the era of popping into the local kirana for essentials is becoming passe.

These platforms deliver not just essential commodities even before one can say, "Jack Robinson", but also electronic goods. In September, when Apple launched its latest iPhone 16 series, Blinkit, Zepto and the rest were ready to deliver these gadgets within 10 minutes of customers ordering them.

Also read: Swiggy’s big bet on Instamart, and the power of Q-commerce

Swiggy CFO Rahul Bothra recently revealed that Q-commerce now constitutes 40 per cent of the company’s traditional food delivery business. The Q-commerce segment is not only growing faster than Swiggy’s food ordering business, but is also poised to overtake it.

Milk and chocolate seller Nestlé India said late last month that Q-commerce is now 50 per cent of its e-commerce business and its fastest channel of growth. Overall, e-commerce is 8.3 per cent of the company’s domestic sales.

Big investments

Swiggy is making substantial investments to fuel this expansion, pouring ₹1,179 crore into Instamart, a move that reflects the company’s aggressive drive to dominate Q-commerce. According to Swiggy's Red Herring Prospectus filed ahead of its IPO, a massive ₹755.4 crore is directed toward expanding its dark stores (small warehouses that enable lightning-fast deliveries) network, and another ₹423.3 crore is for leasing and licensing.

The rapid rise of Q-commerce has fundamentally changed consumer habits, leaving kirana stores, once the cornerstone of neighbourhood convenience, struggling to keep pace.

Platforms like Swiggy Instamart, Blinkit, and Zepto have made rapid inroads by offering near-instant delivery and lower prices, capturing an estimated 25-30 per cent of the market once held by kiranas.

This transition has led to the closure of nearly 2 lakh kirana stores, particularly in metropolitan areas, where consumer expectations have shifted irrevocably toward the speed and ease of digital shopping.

Decline of mom-and-pop stores

Q-commerce's growth potential is vast, too. “The quick commerce market in India currently exhibits a penetration rate of only 7 per cent of the potential market, with a total addressable market at $45 billion, surpassing that of food delivery, indicating that a significant opportunity remains untapped,” says Chryseum, a private market index company in its report on quick commerce.

The rise of Q-commerce, marked by a blend of speed and competitive pricing, has disrupted India’s retail market in a way few anticipated. For generations, kirana stores were the backbone of Indian shopping, offering personalised service and convenience to local communities.

However, as Q-commerce platforms continue to capture market share, kirana stores face an existential threat. A significant factor in this decline is the aggressive pricing strategy employed by Q-commerce platforms, which frequently undercut kiranas by offering discounts that traditional stores simply cannot afford due to their limited profit margins.

Also read: FMCG distributors concerned over rapid growth of quick commerce platforms, seek scrutiny

These platforms promise delivery within minutes, responding to a rising demand for convenience and immediate gratification, particularly in urban areas. This shift in consumer expectations has marginalised kiranas, which cannot match the rapid fulfilment of digital platforms.

Pricing advantage

Swiggy Instamart and its competitors often items priced 10-15 per cent lower than kiranas, leveraging economies of scale and investor funding to offer attractive discounts.

This pricing advantage makes Q-commerce especially appealing to budget-conscious shoppers, drawing them away from neighbourhood kiranas.

The COVID pandemic accelerated the shift toward online shopping, and for many, the convenience of app-based orders has become the new normal.

Consumers who previously relied on kiranas for impulse buys now reach for their phones, making it difficult for kiranas to compete with the digital ease of quick commerce.

Fight to survive

Despite the steep challenges, some kirana stores are innovating to stay relevant. Faced with an urgent need to modernise, a segment of these traditional shops has embraced digital strategies and enhanced customer service, hoping to retain the loyalty of a dwindling customer base.

Some kirana stores are taking steps to digitise their services, accepting orders via WhatsApp and building an online presence. These stores are trying to adapt by offering delivery options and sometimes joining online platforms to extend their reach. However, these changes are often limited to stores with the resources to invest in technology, leaving smaller kiranas vulnerable.

Many kiranas are leaning into their strengths by providing personalised service, where they have traditionally excelled. Store owners who know their customers by name and offer flexible credit (the khata system) hope to preserve loyalty in the face of Q-commerce’s encroachment.

While these adaptations are promising, the financial constraints of kirana owners often limit the scale of transformation. For every kirana that goes digital, many others face closures due to the competitive pressures exerted by Q-commerce giants.

Also read: Explained: Know how Swiggy Instamart can now build your shopping cart in a jiffy

Aggressive expansion

Swiggy’s aggressive expansion of its quick commerce division, Instamart, signals a significant shift in India’s retail landscape.

By investing ₹1,179 crore into the segment — including ₹755.4 crore to expand its network of dark stores and another ₹423.3 crore for leasing and licensing — Swiggy aims to build the infrastructure needed to stay ahead of the quick commerce race. Swiggy’s commitment to Instamart highlights the shift in focus from food delivery to broader quick commerce. This trend will continue as more consumers turn to these platforms for everyday essentials.

Swiggy’s success in quick commerce reflects a broader trend in India, where urban consumers increasingly prefer the instant access and affordability of digital platforms. With quick commerce growing faster than traditional food delivery, companies like Swiggy are capitalising on a lucrative market that appeals to India’s young, urban, and tech-savvy population.

Also read | How e-commerce firm Cashify is cashing in on India's circular economy

“The Quick Commerce Industry In India Market size is estimated at $3.34 billion in 2024, and is expected to reach $9.95 billion by 2029, growing at a CAGR of greater than 4.5 per cent during the forecast period (2024-2029),” Chryeum said in its report.

Challenges

While quick commerce has found fertile ground in India, it faces its own set of challenges. The high cost of maintaining dark stores and offering deep discounts has led to a model that relies heavily on external funding, raising questions about its sustainability. Swiggy Instamart’s rapid growth, fuelled by substantial investments, underscores the importance of scale and hints at the potential risks if funding dries up or operational costs rise.

Additionally, regulatory scrutiny and consumer sensitivity to price could influence the trajectory of quick commerce.

The government may impose regulations to protect traditional retail formats like kiranas, which could affect quick commerce platforms’ ability to maintain competitive pricing and operational flexibility. Moreover, while urban consumers are willing to pay for convenience, many remain price-conscious, particularly for essential goods.

Quick commerce is about more than just speed. The key players in the space need to focus on three critical factors: market share, customer acquisition costs (CAC), and average order value (AOV).

Balancing growth and profitability

Operating in Q-commerce is a high-stakes game with razor-thin margins and heavy upfront investments. And the challenges don’t end with logistics.

Success hinges on attracting new customers while encouraging existing ones to order more frequently. Here lies a crucial balancing act: if CAC (the cost of acquiring a new customer) continues to rise while AOV (the average amount spent per order) remains stagnant, the model risks becoming unsustainable.

Also read | Why Piyush Goyal's criticism of e-commerce giants is not fully valid

Efficient cash flow management becomes essential to managing high costs and intense competition. Building a sustainable business model in quick commerce depends on finding the right balance between growth and profitability.

That’s the high-stakes battle Swiggy, Blinkit, and Zepto are engaged in. Each is vying for dominance in a space where success depends as much on strategic cost control as on rapid delivery.