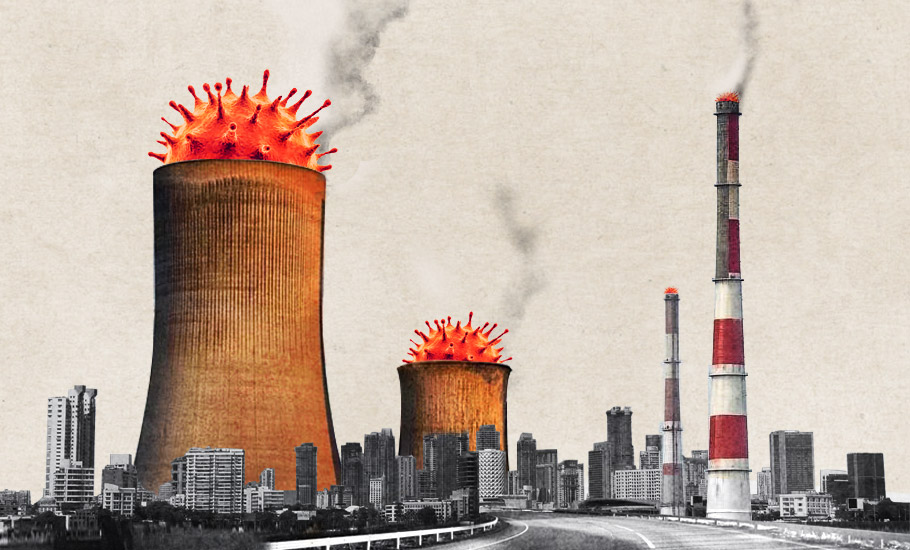

Post-COVID economic recovery may be at the cost of public health, environment

The COVID-19 shock and resultant humanitarian crisis have reinforced the fact that economic destabilisation is inevitable, if health and environmental boundaries of development are not respected. So, has India spent enough in strengthening these boundaries in the aftermath of the pandemic?

The COVID-19 shock and resultant humanitarian crisis have reinforced the fact that economic destabilisation is inevitable, if health and environmental boundaries of development are not respected. So, has India spent enough in strengthening these boundaries in the aftermath of the pandemic?

Like the rest of the world, India too has spent large amounts of money to kick-start its post-pandemic economy but the additional money has not been directed towards recovery measures to support a low-pollution transition.

The various fiscal stimuli (estimated to be equal to 10 per cent of the GDP), which have been announced by the government so far have, on the contrary, been aiding high-carbon economic production. Instead of supporting green initiatives, we seem to be retreating from earlier goals on pollution, emissions and sustainability.

Also read: Economy emerges out of recession, GDP grows 0.4% in Q3

In its ‘State of India’s Environment 2021’ report, the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) points out that public health and climate goals will slip out of reach quickly, if India misses this opportunity to turn the economic recovery packages into green recovery.

Already, the cost of the pandemic has been staggering. The CSE study points towards a “pandemic generation” of 375 million children under the age of 14 years, suffering from long-lasting impacts such as being underweight and stunted and anyway, enhanced child mortality could also be on the horizon. Several Indian states had failed to ensure food continued to reach the underprivileged under designated state schemes during the lockdown.

The CSE report cites the Jharkhand example, where anganwadis did not provide food for children. For many poor children, the food at anganwadi centres was the only nutritious and filling meal of the day. In Jharkhand alone, more than half a million children can become severely malnourished or underweight. Another half a million can become wasted. In the three states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh, more than five million new malnourished children may be the by-product of the pandemic and the subsequent lockdown.

Also read: How you can make the planet a cleaner, greener place in the New Year

But instead of doubling down on green development goals, aiding the fight against malnutrition and helping the underprivileged, India has gone ahead and undone some of the good work of the past.

The CSE report lists some instances:

Autos: The automobile industry is seeking to delay the implementation of Corporate Fuel Consumption Standards for passenger cars scheduled for implementation in 2022-23. Pushing back the timeline for implementation will impact emission goals. Also, while the government has announced a Vehicle Scrappage policy for promoting the sale of new vehicles, the “unsafe” dismantling of the population of ageing vehicles is causing huge wastage of material and contaminating water, soil and air, thereby increasing public health risks. Alongside vehicle scrapping, India also needs a sustainable scrappage infrastructure.

Power: India’s power plants have already pleaded for a delayed deadline to meet the new standards beyond 2022; about 70% of the plants cannot meet the standards by that deadline. Also, the economic recovery package announced by the government for cash-strapped DISCOMs is also not linked to reforming them but to allow greater fund flow to make investment in emissions control technology for nitrogen oxides and sulphur dioxides more bankable.

The Union Budget for 2020-21 has proposed retirement of old thermal power plants. Subsequently, 5.1 GW has been earmarked for shutdown. Such decommissioning can help the debt-ridden utilities with contractual fixed cost obligations and improve the utilisation of more efficient and cleaner plants. This can also avoid the cost of retrofitting old, dirty plants. But, this will have to be taken forward.

Also read: Budget 2021 bets heavily on a sharp recovery, and therein lies the risk

Coal: The fiscal stimulus packages announced so far call for private investments and ease-of-doing business in the coal sector for accelerated commercial coal mining while removing end-use restrictions. Rules on ash content of coal have also been waived off. This will flood the market with dirtier and cheaper coal. In any case, the influx of cheap and low-quality coal can increase industrial consumption of coal, especially in small-and-medium-scale units. Resisting this trend will be tough because cleaner fuels, like natural gas, are more expensive than coal. While coal is under GST and is taxed low, natural gas attracts state taxes and is more expensive.

Public Transport: India’s 14 State Road Transport Undertakings have suffered massively during the pandemic with record low ridership numbers. Then, there is now the additional burden of safety protocols and social distancing requirements, adding to cost of operations. Net losses of these SRTUs have escalated, revenue has shrunk and the annual viability gap-funding need has increased by 69 per cent.

Public transport revival is a critical part of the clean air and climate solution. But without a bailout strategy, India cannot meet its target of augmenting the bus fleet to 188,500, as estimated by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development.

EVs: Without a proper stimulus package, there are serious dangers of the electric vehicle (EV) programme getting derailed. Electric vehicle registrations are down, and a longer-term incentive programme is needed to lower the upfront cost and the total cost of ownership and bring cost parity between EVs and vehicles operating on internal combustion engines.