Sikhs, Hindus coming to India from Afghanistan may run into CAA hurdle

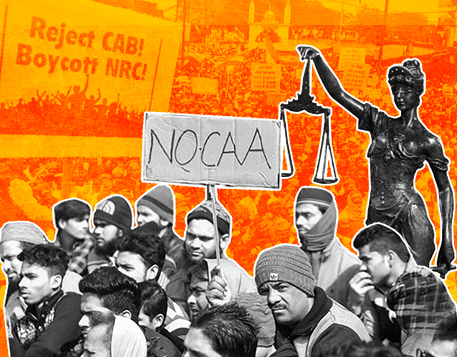

Thus the Modi government’s decision to bring in the CAA was not motivated by a desire to help migrants, but to buttress its own narrow majoritarian agenda.

The exodus of Afghan refugees — Hindu, Sikh and Muslim — to India following the Taliban’s almost effortless conquest of Afghanistan has once again thrown the spotlight on the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, and its possible use in ameliorating the circumstances of the new arrivals.

Hardeep Singh Puri, the minister of petroleum and natural gas and minister of housing and urban affairs, claimed in an August 22 tweet that “recent developments in our volatile neighbourhood & the way Sikhs & Hindus are going through a harrowing time are precisely why it was necessary to enact the Citizenship Amendment Act”. But whatever the minister may claim, one thing is clear: in its current form, the law will not come to the rescue of the refugees — Sikh or Hindu or Muslim.

Here’s why: The CAA offers a narrow pathway for Indian citizenship to undocumented migrants from three countries — Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan — even if they have entered India illegally, as long as they aren’t Muslims. Only our Muslim-majority neighbours are included in the CAA’s ambit. Sri Lankan Tamils and Rohingyas from Myanmar are not, for example.

The refugees India is accepting from Afghanistan are coming via a legal process. In fact, the government has introduced a new category of e-visa for Afghan nationals to fast-track their entry into the country.

India is not a signatory to either the 1951 UN Refugee Convention or the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. In fact, the country does not have a policy on refugees at all. All refugees are classed as “illegal migrants”.

India currently hosts more than 450,00 “refugees” — from Afghanistan, Tibet, Bangladesh and beyond. They are expected to return to their home countries once the situation there returns to normal. Under the yet-to-be implemented CAA, illegal migrants can be granted citizenship if they are non-Muslim, on the grounds that they are refugees; only Muslims will be deported to their home countries. Furthermore, the Act has a cutoff date, December 31, 2014. Anyone who arrived in the country after that date, including those who have streamed in in the past few weeks, is ineligible to be considered.

What about those who are already here?

South Delhi’s Lajpat Nagar, popularly called ‘Little Kabul’, is lined with Afghan businesses — eateries, bakeries, pharmacies, supermarkets, etc. At least two generations of Afghan refugees have made Lajpat Nagar their home since 1979 when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan. But despite being in India for decades, these refugees – mostly Muslims – are still struggling. They cannot even get a SIM with the documents they currently possess, let alone education, jobs and housing or citizenship.

Last week, they held a protest demanding basic rights. The UNHCR office in New Delhi grants refugee status to Afghans and citizens from other strife-torn nations and issues identification cards. However, as India is not a signatory to the refugee convention, refugees are unable to enjoy the rights ensured by the UN in other countries. The ID issued by the UNHRC is not widely recognised by authorities in India. The Afghans are thus left fighting a complex bureaucratic process.

It is a similar story for the Sikhs and Hindus from Afghanistan. In January The Wire carried a report documenting the travails of several Sikh and Hindu Afghans who came to India — in some cases decades ago — expecting citizenship and dignified life. They are still waiting.

“It is painful to keep waiting for legal citizenship in a country we thought was our natural homeland when we fled here years ago,” the report quoted a 64-year-old man, Amrit Singh, as saying. His wife, 62-year-old Anant Kaur, a refugee from Afghanistan’s Nangarhar Province, who had settled in Amritsar in the late 1990s, died in May 2020, still praying for Indian citizenship.

The Modi government’s decision to bring in the CAA was not motivated by a desire to help migrants, but to buttress its own narrow majoritarian agenda. The CAA is a tool to further push the BJP’s narrative with respect to domestic politics in India. Sikhs and Hindus of Indian origin who have arrived in India in the past few weeks have a long – perhaps never-ending – wait ahead.