Kerala: Left changes narratives; Congress in a quandary

To sum up, the Congress in Kerala displays shallow enthusiasm for new political changes. Whether it is politics of caste, gender, sexuality, or environment, the Congress party declares solidarity which is largely superficial.

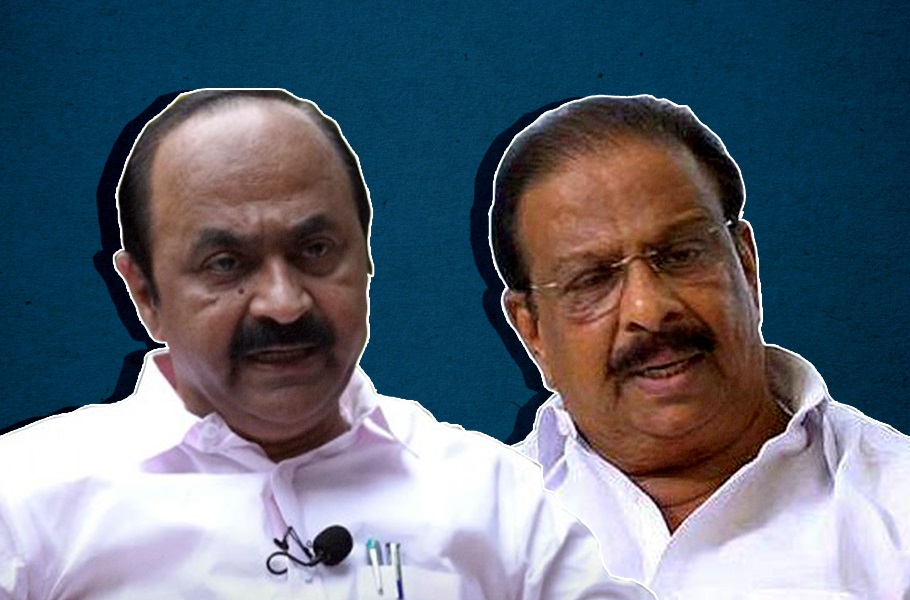

The Congress party, after the recent Kerala Assembly election debacle, is trying to turn a new leaf by inducting a new-look team. In May last week, the Congress appointed VD Satheesan, a young and progressive leader, as the Leader of Opposition, signalling the party’s preference for the youth. On Tuesday (June 8), K Sudhakaran, an MP from Kannur, was made the KPCC chief — another departure from the usual Congress playbook.

This is probably triggered by a generational shift initiated by the CPI(M) and CPI by introducing new faces both in the state Assembly and the Council of Ministers. While this makeover is being cheered largely by social media, the worry is how long the novelty would last.

If local media is to be believed, a section of the party backed Kodikkunnil Suresh, a Member of Parliament (MP) from Mavelikkara. Another section favoured K Sudhakaran, an MP from Kannur. While Suresh is a Dalit, Sudhakaran belongs to the Ezhava community, classified as OBC in Kerala.

Also read: Pinarayi Vijayan 2.0: Poverty alleviation, education key objectives

At one level, the race for the KPCC president’s post could be construed as inner-party democracy at work, but at another, this brings out the clash of caste identities within the party. The Congress party’s move, at least the discussions in this regard, to appoint a Dalit leader as the party chief should certainly be welcomed. But the question is whether it would promote a politics based on social justice or the Congress, as usual, is coopting communities for mere symbolism?

Hopefully, the change is not cosmetic, made to paper over the larger challenge the party is likely to face from the BJP in the coming days. Interestingly, while Sudhakaran has been a strong critic of the CPI(M), he has been soft on the BJP. Recently, he made no efforts to deny rumours of his joining the saffron party. Besides, the Congress has always been ambiguous, displaying little honesty while taking a stand on many contentious issues.

Is CPI(M) the new Congress?

The Congress now seems to be staring at its mutant variety in the form of CPI(M) as the Left seems to have adopted the narrative and programmes of the grand old party. The CPI(M) now talks of development, welfare, secularism, and swears by the Constitution; almost sounding like the yesteryear Congress. What was earlier described derisively as “neoliberal reforms” by the CPI(M) is no longer untouchable for the party. The much-spoken Kerala Infrastructure Investment Fund Board (KIIFB), the state-owned developmental finance institution, is the Left government’s way of harnessing global finance capital to carry out its infrastructure work.

Also read: Black money scam hits Kerala BJP

While the Congress had to compromise on its stand against Hindutva, most notably during the Sabarimala issue, the CPI(M) took a far better stand than the former. [That the party changed, rather diluted, its stand later is a different issue altogether].

Interestingly, during their five-year rule, the CPI(M ) leaders invoked Nehru and spoke about his secular legacy more than any Congress leaders. In short, the CPI(M) plays with the Nehruvian Legacy of secularism, development, and socialism.

LDF is the new UDF

Besides governance, the CPI(M) seems to be shaping its coalition politics on the same lines as the Congress. Since the advent of the two-front coalition in the state, the Congress-led United Democratic Front (UDF) has been functioning by co-opting political representation of dominant communities and safeguarding their interests. As opposed to this, the CPI(M)-led LDF was formed based on ideology rather than narrow community interests.

Now, there is a visible shift, with the Kerala Congress (M), one of the major UDF allies, switching to the LDF. The KC(M) largely serves the interests of elite Christian groups. Besides, CPI(M) representatives in the Muslim-majority regions represent the rich and creamy layer of that community and serve their interests.

Now, the difference between the two parties is not about the programmes per se, but their working style. While the Congress is a loose association of dominant communities, the cadre-based CPI(M) operates in a far more disciplined fashion.

Politics of common sense

The worry for Congress is not only about the CPI(M) adopting its political agenda but also that it is cleverly using its populist slogans, working style, and idioms. Political theorists believe these days that political affiliations need not always be based on “meticulous rational deliberations”. It could also be about emotions, aesthetic sensibilities and practical wisdom, etc.

If one were to look closely at the working style of the CPI(M), it would be clear that its politics was not only based on classical Left sensibilities, but also populist political imagination and language, which was for long what Congress advocated.

Both the Congress and the CPI(M) are national parties, but with different working styles at the regional level. However, a difference is that regionalism for Congress in Kerala is about the party and its working style. A Congress state unit may not find it difficult to ward off interference from its ‘high command’ in New Delhi. Their justification is that national leaders are not knowledgeable enough to comment on the state unit of the party.

But, on the other hand, the CPI(M)’s regionalism is not about the party but about a sub-national sentiment, even pride, at times. One of the expressions Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan has been frequently using during his press conferences is, “ee naadu” meaning “this land”, in Kerala. He often highlights Kerala’s social and historical uniqueness where people live peacefully with fraternal sentiments.

The CPI(M) could effectively encash on another factor, which would have otherwise been the Congress forte: benevolence and charity. Kerala is a highly religious society and the CPI(M) is making use of people’s beliefs in charity and almsgiving. Though this may look harmless, a closer examination reveals that these notions are based on a set of values and norms that are feudal in character.

New political questions

Hence, there is a political lacuna of the Left politics that the CPI(M) seems to have abandoned. It is quite obvious that a bourgeois party like the Congress can’t find any space in its dictionary for expressions like class consciousness, dialectical materialism, surplus value, the dictatorship of the proletariat and so on.

The new, mutated CPI(M) seems more interested in addressing questions of backwardness, representation, land, and resource ownership, and social distribution of risks through welfare-driven initiatives.

The green enthusiasm, its shallowness

Environmental politics was one of the themes the Congress party and its coalition partners embraced in the mid-2000s. Local media used the term “Green MLAs”, referring to a few legislators in Kerala when the United Democratic Front (UDF) was in power between 2011 and 2016. VD Satheesan, Leader of Opposition now, led the Green Brigade then.

Now, after assuming his office as Leader of Opposition, he doesn’t seem to be the same green warrior though it’s too early to conclusively say so. Even local media seems to have forgotten that. In 2012, the Congress had launched a blog that was updated till 2015. After that, everything stopped.

Also read: How Kerala is nurturing young volunteers for crisis situations

The CPI(M), on the other hand, could milk the sentiments against ‘environmentalism’ in the Western Ghats. PV Anwar, a powerful businessman who courted controversy for his alleged land encroachment and illegal constructions, now an MLA from Nilambur, had twice contested and lost as an independent candidate representing the politics against the Gadgil Committee report which favoured conservation. Later, when LDF fielded him as their candidate, he won on the trot.

The caste question

Caste composition has changed within the newly elected LDF legislative party and its council of ministers. According to Kancha Ilaiah, an intellectual and theorist, the CPI(M) of Kerala has moved away from the Bengal unit of the party where the leadership is full of “Bhadralok” or upper-caste Hindus.

Kerala has chalked a different plan where the leadership-baton has changed hands from a Brahmin chief minister to a non-Brahmin one, and then to OBC twice. (VS Achuthanandan and Pinarayi Vijayan now).

The upper castes still dominate in Parliament, an anachronism, as the cadre base is largely made up of socially backward communities. The outgoing ministry of Pinarayi did take some retrograde steps such as reservation for forward castes, which perhaps, sounds like the failed Bengal model.

To sum up, the Congress in Kerala displays shallow enthusiasm for new political changes. Whether it is politics of caste, gender, sexuality, or environment, the Congress party declares solidarity which is largely superficial.

For instance, the party’s 2016 election manifesto spoke of ‘Rohit Act’. [The name has been derived from Rohith Vemula, a PhD student from the University of Hyderabad, who committed suicide, alleging Dalit discrimination]. The same manifesto proposed another piece of legislation to stop women from entering the Sabarimala shrine. If the Congress party works for those on the margins and leads new social movements which empower the backward communities it can think of a revival in the state. But then the party may have to take a hard turn which includes opposition to reservation for the upper castes.

Can the party do it? The recent history of the party does not evoke any such confidence.

(Ranjith Kallyani is a Research Scholar at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at IIT Bombay. He can be contacted at ranjithkallyani@gmail.com)