India’s economic survey and the quest for a $5 trillion economy

Since nothing in this world makes real sense without understanding its context, let’s start by looking at the background of the Economic Survey for the last fiscal year tabled in Parliament on Thursday.

The survey — basically, the finance ministry’s view on the financial roadmap based on previous year’s data — has been released in an environment of falling GDP, record unemployment and a delayed monsoon on the gloomy side. On the brighter side, India has entered into a five-year phase of political stability and a mandate for the government to pursue its economic vision without too much opposition.

But, the overarching context for the survey is Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s promise of turning India into a $5 trillion economy by 2024. It is this promise that has become the defining philosophy, a sort of holy book, for the finance ministry.

Also Read: Economic Survey 2019 denies economic slowdown, calls it ‘slight moderation’

India is currently a $2.8 trillion economy (nearly 190 lakh crore in Indian Rupees). As India’s chief economic advisor KV Subramanian said while releasing the survey, the economy needs to register a sustained growth rate of 8 per cent to ensure it nearly doubles in the next six years.

India is currently the world’s sixth largest economy in terms of GDP. To put this in perspective, the US and China, the top two, are $21.5 and $14.2 trillion economies. If India grows at 8 per cent, it would become the third biggest economy by 2024-24.

But, growing at 8 per cent for six years is a tall order. During the past five years under Modi, India grew at a rate of around 7 per cent. In the previous financial year, it was pegged at 6.8 per cent. Even this data was later questioned by former chief economic advisor Arvind Subramanian, who said it may have been exaggerated by at least 2 per cent.

Also Read: Union Budget: Economic Survey pegs GDP growth at 7% in FY20

Notwithstanding the controversy, it is clear that the challenge before the Modi government is to make India grow at 8 per cent. This objective is aimed at generating more jobs, eradicating poverty, more taxes and a better life for citizens. And, the survey should be seen in this backdrop.

The current CEA says India needs to embark on a virtuous cycle of savings, investments and growth to achieve this objective. With this in mind, he has proposed a better investment in climate, easier labour laws, predictable policies — investor friendly environment that doesn’t change — and focus on attracting domestic and foreign investors. Like China and the Southeast Asian countries, he wants India to invest, generate jobs and concentrate on exports.

So, can the government achieve its objective?

For the GDP to grow at a high rate consistently, three things are important: inflow of investments, low inflation and a stable currency. Since India has been among the world’s fastest growing economies over the past few decades, domestic and foreign investments have been steady. But, the precipitous fall in the GDP — 5.8 per cent from 6.6 per cent — in the first quarter of the current fiscal points to a slowdown that the government needs to reverse. This rate is the lowest in 51 months.

Inflation has been in control over the past few years, staying around 4 per cent. The economic survey sees a fall in crude prices in the next few years, thus, helping India control both its inflation and import bill. This, according to the survey, would contribute to the long-term goal of a $5 trillion economy. But, how crude rates move would depend on the international market, especially the ongoing tiff between Iran and the US. Any change in the status quo would peg down government estimates and have a bearing on prices, and thus, consumption.

The CEC has suggested some innovative methods for boosting growth and investments. He wants India to mine its data, make it available for public, to turn it into a money-spinner. He wants governments to treat data as infrastructure — something that needs to be invested in and then monetised.

In the Indian context, it is no matter of surprise that urban and rural household voters have diametrically opposite views when it comes to issues such as inflation.

Higher prices of food grains help win rural vote, but this is at the expense of the urban voter. While rural voters of course consume food grains, the net is that the farmers’ income goes up when prices of food grains rises. This is an economic contradiction of output vs input.

Also Read: Union Budget: India needs to spend more to modernise weapons

The rural output appears on the expenditure side of the urban voter and vice versa, and products including consumer products that are output in urban constituency are in the expenditure side of the rural voters’ household.

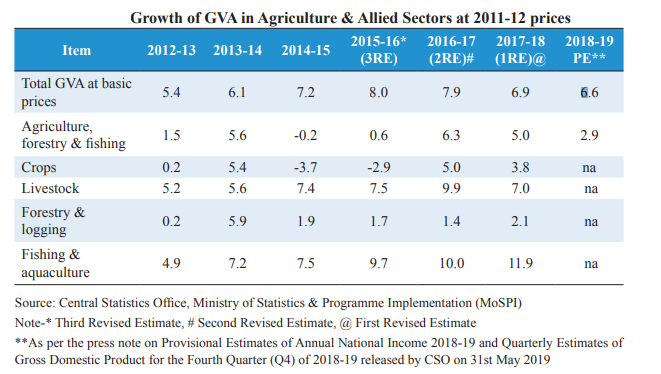

In the context of doubling farmers’ income by 2022, this just does not seem possible with low food inflation (meaning lower price realisation), falling yields and poor access to markets for agriculture produce. The economic survey today shows GVA of agriculture to be 6.6 per cent and one wonders how this would help us double farmers’ income by 2022.

For the moment, the survey reads more like a document of intent and ideas. The proof of the implementation would soon be seen in the economy that’s currently stuttering.