Galwan clashes: India can either resist China or meekly accept its hegemony

A tired smile appeared on Zorawar Singh Kahluria’s face as he surveyed the snow-covered Mayum La ahead. He was expecting a strong contingent of the Qing army on the narrow road that stretched through the pass and led to western Tibet. Finding the road empty, Kahluria took a deep breath and ordered the Khalsa army to roll ahead.

Through the summer of 1841, Kahluria, called the Bonaparte of the Khalsa Empire, had made lightening moves that helped hwis 4000-strong force sweep through Tibet. By the time Lhasa could organise a counter, Kahluria had already settled deep into Tibet, turning Taklakot on the Nepal Border as his base.

But, in the winter, the Khalsa army had given up all its gains as a 6000-strong force of the Qing dynasty cut-off Kahluria’s supply lines and recaptured most of the Tibetan bases. Deprived of fuel, food and reinforcements, his army decimated and maimed by frostbite, Kahluria decided to fight his way back to Ladakh through the narrow Mayum pass.

On December 14, finding the road cutting through the pass empty, the Khalsa army started marching in three units, its flags fluttering and drums beating. It was a trap. Just as the army hit the narrowest part of the Valley, it was ambushed by the enemy hiding behind the mountains. A Tibetan horseman charged at Kahluria and put a lance through his heart, someone else beheaded him. Within minutes, the snow had turned red with the blood of Khalsa soldiers.

History has a cruel penchant for repeating itself, most of the times as a tragedy. So, it was 1841 once again for the Indian army on the intervening night of June 15-16 when at least 20 of its soldiers were surrounded by the PLA. Under the white light of the moon, the snow covering the Galwan Valley and the water in the nearby Pangong Lake were laced with the blood of Indian soldiers, perhaps in the most gruesome way—with stones, clubs and in hand-to-hand combat. There are reports also of casualties on the Chinese side, but Beijing has not given any numbers so far, leaving the actual count to just conjecture.

The 1841 ambush, re-enacted almost to the script in June 2020 is an important event in Sino-Indian history. Kahluria was the last Indian to lead a victorious army through Tibet. Once he was defeated, the Chinese dynasty and the Khalsa army—led by Dogra general Gulab Singh, the man who was to later buy Jammu and Kashmir from the British—signed the Treaty of Chushul in September 1842. This treaty gave India rights over Ladakh and the Chinese over Tibet and imposed a code of non-interference on both sides.

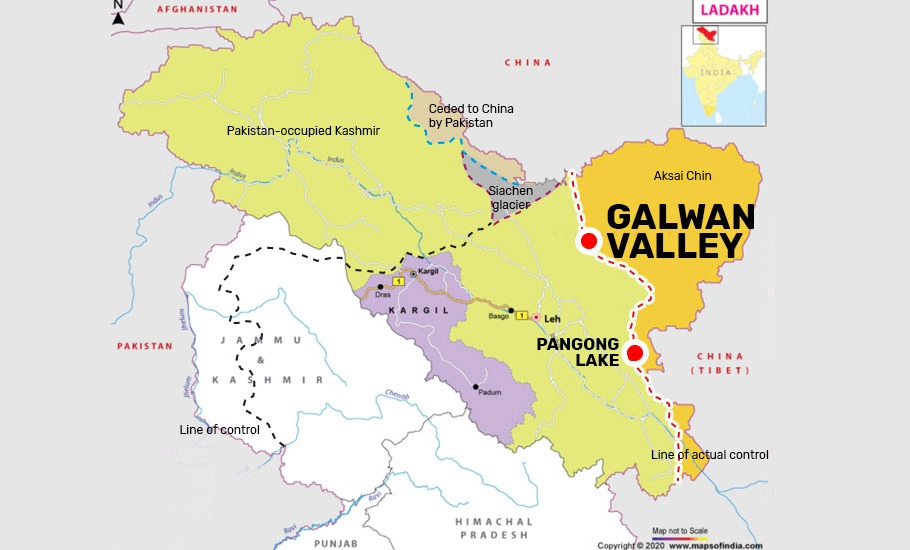

But, the problem is China has always kept the Ladakh issue open and tried to extend its borders into the Indian territory many times. The Galwan Valley is especially important for it since it lies between Ladakh and Chinese-controlled Aksai Chin and the only direct road to Xinjiang and Tibet runs through it. So, the valley has been a prominent target of Chinese predatory attempts.

Tension had been building in this area over the past few weeks since the PLA entered deep into the Indian side in the Galwan Valley and started making provocative forays in the Pangong Lake, a third of which is under Indian control.

Ajai Shukla, a well-known strategic affairs expert, believes the PLA has occupied several important spots on the Indian side:

“In the Pangong Tso sector, Chinese troops continue to occupy the area up to Finger 4, which includes 8 kms of Indian-claimed territory between Finger 8 – which is the Indian version of the LAC – and Finger 4,” Shukla’s blog noted.

In the Galwan River sector, the PLA still occupies the area up to PP 15 and PP 17 and the heights overlooking the Galwan valley.

Reports are also emerging that Chinese troops have entered the Depsang area, which lies to the north of Galwan, in the Daulat Beg Oldi sector. Here they have reportedly secured the areas up to PP 12 and PP 13.

This could mean that the Indian Army has one more sector to safeguard, besides the Galwan and Pangong sectors where the PLA earlier encroached, and the Harsil sector in Uttarakhand, where the PLA has also built up troops. Depsang is the same sector where India and China saw tensions in 2013.

The latest incident reportedly happened when around 50 Indian soldiers were surrounded by the PLA on the Indian side and attacked with clubs and stones.

It is clear from Chinese tone and manoeuvres that it is testing India’s resolve and strategic depth by repeatedly pushing back the Line of Actual Control and aggressively reacting to India’s efforts to regain lost territory. The recent is part of its overall strategy of flexing its muscles in Asia and the Pacific region, exemplified by the clamp down on Hong Kong, posturing against Taiwan and aggressive moves in the South China Sea. Seen in the backdrop of its rivalry with the US, it is evident that China is trying to position itself as a super power not averse to taking on regional rivals like India.

A few things about the Chinese reaction to the Galwan Valley clashes are important for India. Unlike New Delhi, it has not given details of the incident or casualties the Chinese side. Beijing has only said there were casualties on both sides because of India’s aggressive moves and illegal forays across the LAC. This ambivalence will help it stick to the argument that it is a victim of Indian aggression and yet evade domestic pressure that would have been inevitable if the numbers on the Chinese side were big. Notice China’s argument behind not revealing the numbers—it says this would lead only to comparisons and demands for revenge. This China, argues, is a sign of goodwill but is actually a message to India to not give in to cries from the Indian media and public to avenge the attack, since it is taking pre-emptive measures to ensure the public ire is not stoked.

The other important take away from the clash is that China is asking India not to overestimate its (India’s) military or diplomatic depth by relying on the US. This message is clear from the line its mouthpiece Global Times has taken on the incident.

In recent years, New Delhi has adopted a tough stance on border issues, which is mainly resulted from two misjudgments. It believes that China does not want to sour ties with India because of increasing strategic pressure from the US, therefore China lacks the will to hit back provocations from the Indian side. In addition, some Indian people mistakenly believe their country’s military is more powerful than China’s. These misconceptions affect the rationality of Indian opinion and add pressure to India’s China policy.

China and India are big countries. Peace and stability along border areas matter to both countries as well as to the region. New Delhi must be clear that the resources that the US would invest in China-India relations are limited. What the US would do is just extend a lever to India, which Washington can exploit to worsen India’s ties with China, and make India dedicate itself to serving Washington’s interests.

China seems to be factoring in two things while evaluating the Indian response—cries for avenging the attack by a hawkish media and Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s image of a leader who responds to attacks on Indian interests. Only a few days ago, home minister Amit Shah had claimed India is the only country after Israel and the US with the ability to defend its borders. To pre-empt this, it has claimed the gap between Indian and Chinese military strengths is too big for New Delhi to ignore. Also, it has announced that China seeks peace but is ready to defend its strategic interests.

India’s challenges, thus, would be many. One, it will have to ensure de-escalation without surrendering the territory China has already seized. Two, it will have to convey to public that India is capable of reacting to Chinese aggression, avenging attacks. A part of this objective would be achieved by claiming that casualties on the Chinese side were higher. But, in the absence of clinching evidence, this argument would find few takers. Three, and this is the biggest headache, the Chinese postures would encourage its regional allies like Pakistan and Nepal, who are already heckling India over border issues.

China’s ultimate objective is to make India accept Beijing as the big boss of the region, and the evolving counter to the US. Indian can responds to the Galwan incident primarily in two ways. It can react aggressively by avenging the killings and regaining lost territory, either through diplomatic measure or military muscle. Or, it can let China have its way by accepting the status-quo in the hope that this will ensure peace in the region. The first option will prove India, like Kahluria, is willing to fight its way out of the Chinese trap, even if more blood is spilled. If it takes the option of staying silent–and managing the public mood through unverified claims—New Delhi will end up accepting China as the lord and master of the region.