100-year-old play's ban not justified, could have tweaked offensive parts

AP government move to prohibit the staging of ‘Chintamani Padya Natakam’ impinges on the freedom of creative expression

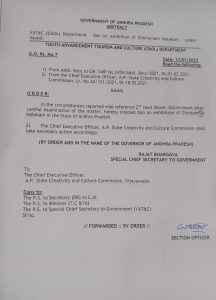

The Andhra Pradesh government has inflicted another blow on the freedom of literature and creative expression by imposing an arbitrary ban on Chintamani Padya Natakam, a highly successful 102-year-old Telugu play, on the demand of the Arya Vysyas community.

The order simply said the play is banned, without assigning any reason or substantial material to justify the ban. The poetry-based play has been staged thousands of times over the past 100 years all over the Telugu States, India and wherever there is a sizeable Telugu speaking population abroad.

Social reform drama

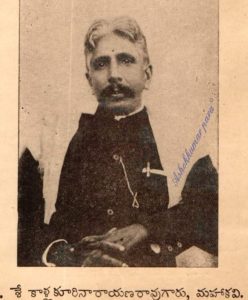

Kaallakuri Narayana Rao (April 28, 1871 – June 27, 1927) penned the social reform drama in 1920. The story was inspired from some of the families that Kaallakuri knew, which crumbled because the breadwinners sold all their ancestral and self-acquired properties and poured the money into brothel houses.

This is one of his most popular works, and secured him the title of Mahaa Kavi, or ‘great poet’. By 1923, it was staged 446 times at different places. It also reached millions in the form of a printed book with several editions.

Kaallakuri was an ardent social reformer, poet, drama writer and director, and editor and owner of a literary magazine. He advocated inter-caste marriages a century ago — he himself married a woman born in a caste that is known to pursue prostitution as a profession. He was expelled from his own caste, but that did not deter him.

The play is centred on Chintamani, a prostitute who challenges the social evil of influential men having a prostitute as a mistress. Families were often said to have been ‘destroyed’ as men splurged the household money on visiting brothels. Kaallakuri’s other writings also seek to end social evils such as alcoholism (Madhu Seva) and dowry harassment (Vara Vikryam, or ‘sale of bridegroom’).

Chintamani, a story of sinning and repentance

In Kaallakuri’s famous play, Chintamani is a beautiful young lady born in the Kalavanthula caste (who generally pursued prostitution as a profession), in whose lure several rich and young men lose their health and wealth. Bhavani Shankar and Subbi Shetti are among the influential men who lose all their wealth due to the machinations of Chintamani’s greedy mother.

Chintamani asks Bhavani Shankar to bring over Bilwa Mangala, a Brahmin, and he obliges. Though a Krishna devotee with several responsibilities, Bilwa Mangala gets enamoured of Chintamani and neglects his parents, who finally die for want of care. Both Chintamani and Bilwa Mangala begin to realise the adverse effects of prostitution, and this forms the crux of the story.

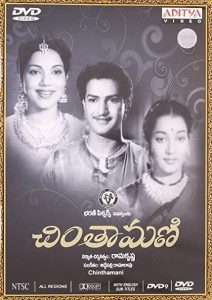

The play has also been made into films twice — in 1933 and 1956 — both titled Chintamani. The later version had top stars such as NT Ramarao, Bhanumati and Jamuna playing important roles.

The character Subbi Shetti is a rich merchant belonging to the Arya Vysya community, who loses all his wealth and ends up as a street hawker of eatables. His affair with Chintamani is depicted with humour and satire. Though the original play was well scripted with a strong social message, the drama companies and local theatre groups subsequently inserted cheap and crass dialogues, and added vulgar dances based on film songs with an overdose of obscenity. As this drew audiences, the vulgarity went on increasing, bringing down the image of Chintamani as socially relevant work.

These interpolations over the past 50 years resulted in the play’s characters losing the original persona given to them by the writer. The Arya Vysya community associations objected to how the Subbi Shetti character was portrayed, and demanded a total ban on the play.

Alterations may have sufficed

Even as the community celebrated the ban when it was imposed, the AP government’s move triggered widespread resentment. The government did not seek opinion or place the proposal for consultation or public comment. Except that their sentiments were hurt, the Arya Vysya community also did not give detailed reasons for their demand.

The government could have directed the theatre groups to strictly adhere to the original script and avoid vulgar additions. Alternatively, it could have asked for the character’s name to be changed to just Subbi, dropping the caste name, and altered his get-up so that it didn’t reflect any ‘caste attire’.

The total ban on the play is criticised as unthoughtful and unwarranted, besides ignoring the rich culture of drama that waged a war against social evils a century ago.