- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

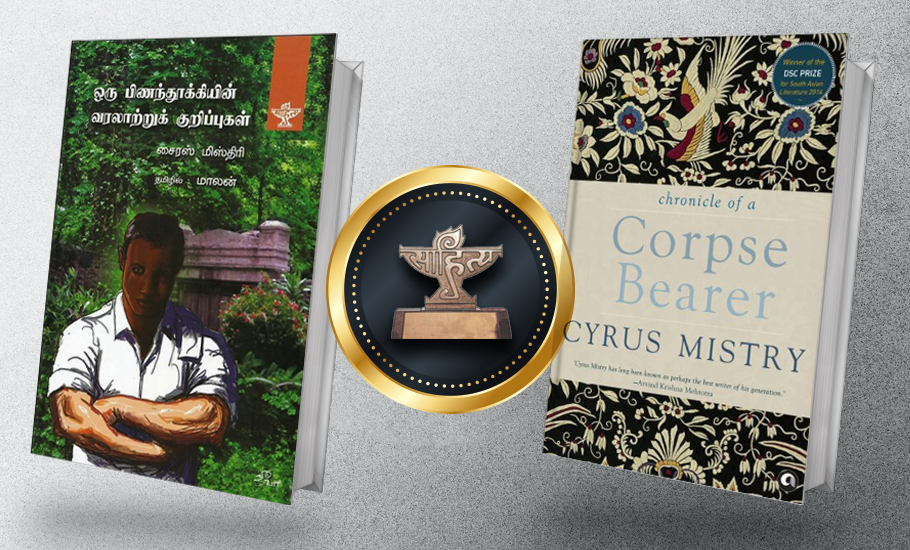

Why Sahitya Akademi to a celebrity editor sparked a literary row in Tamil Nadu

Awards, particularly to regional literary works, have often courted controversy, at least in the Tamil literary world. The Sahitya Akademi Translation Prize 2021, announced recently, to senior journalist Maalan (V Narayanan) for the Tamil translation of Cyrus Mistry’s novel Chronicle of A Corpse Bearer, has ruffled quite a few feathers this year. Maalan’s translation of Mistry’s novel...

Awards, particularly to regional literary works, have often courted controversy, at least in the Tamil literary world. The Sahitya Akademi Translation Prize 2021, announced recently, to senior journalist Maalan (V Narayanan) for the Tamil translation of Cyrus Mistry’s novel Chronicle of A Corpse Bearer, has ruffled quite a few feathers this year.

Maalan’s translation of Mistry’s novel under the title Oru Pinanthookiyyin Varalaatru Kurippugal was published by the Sahitya Akademi in 2019. This is the first of Malaan’s several translated works that has fetched him an award.

The announcement sparked controversy over the Akademi’s decision of handing out the award to one of its own ‘members’. Some within the literary community though don’t agree with the contention.

“There are four committees in the Sahitya Akademi – the financial committee, the general council, the executive board and the advisory board. Although Maalan is a member of the general council, he is not a member of the executive and the advisory boards. Hence, no rules were violated in choosing him for the award,” R Shajahan, a writer based in New Delhi, tells The Federal.

But critics are not satisfied and the Tamil literary circle is agog with objections. Many believe that even though legally it may have been okay to choose Maalan for the award, it’s “morally wrong to award a member of the Akademi”.

In their defence they cite the usual practice in media houses while conducting contests with a disclaimer that none of the employees or their immediate family members are eligible to participate. However, it is not just the decision to award Maalan that is being questioned but also the existence of the Akademi’s Tamil division as a whole.

Shajahan added that the speed at which the work was selected for translation, its subsequent publication and being chosen for the Akademi award is mind-boggling.

“Maalan became a member of the committee in 2018. His translation was published in 2019 by the Sahitya Akademi. It has been chosen as the best translated work in Tamil for the year 2021. I know of a writer who has shown an interest to translate a work for the Akademi but he hasn’t been given permission by the Akademi even after three or four years. On the other hand, the Akademi’s promptness shown in Maalan’s case has definitely made people think that there may be a political lobby behind the selection process,” he says.

Interestingly, none of the objections over the award have anything to do with Maalan’s craft. Even those criticising the decision to award Maalan have openly admitted that he has indeed done justice to the original work. The use of South Chennai colloquialism in the Tamil version of the book, they say, has made the entire plot more relatable to the Tamil readers.

The plot

Set in the pre-Independence era, Mistry’s novel is a love story of a Parsi couple. Even though lead characters Phiroze Elchidana and Sepideh belong to the same community, their family professions are different. While Phiroze is born into a priest’s family, Sepideh, older than Phiroze, is the daughter of a corpse bearer.

Due to the personal rivalry between Sepideh’s mother Rudabeh, who died three years after giving birth to her daughter, and Phiroze’s father Framroze, Sepideh’s father Temoorus decides to exact a revenge on Phiroze’s family using the love affair as a trump card. Temoorus tells Phiroze that if he wants to be with Sepideh, he has to turn into a corpse bearer. Whether Phiroze accepts the condition or not and what happens next is what the rest of the story is about.

Mistry’s novel, based on a true incident in the life of a corpse bearer in Mumbai, gives a detailed view of the lives of the Parsi community, especially the khandhias (the corpse bearers). The story is sprinkled with events related to India’s freedom struggle like the Non-Cooperation and the Quit India movements. In the end, the author also touches upon the effects of the drug Diclofenac on vultures and how that created a problem for the Parsi community in disposing of bodies at the Tower of Silence.

And this is where Maalan shines in poignantly bringing back to life Phiroze Elchidana, the narrator of Cyrus Mistry’s second novel published nearly a decade ago. But that certainly didn’t seem enough to turn the tide in favour of Maalan.

“The problem with the Akademi is its members are mostly either academics or ‘commercial writers’. They don’t have an understanding about modern Tamil literature. We have far better works than the one which has been chosen for the award,” says Veli Rangarajan, writer and theatre artist.

The Akademi, Rangarajan adds, didn’t even consider writers like Pudhumaipithan and CS Chellappa, who were masters of Tamil literature.

“Chellappa contributed to Tamil poetry and literary criticism since 1966. But he was given the award only posthumously in 1997. Even if he were alive at the time, there was every possibility he wouldn’t have accepted the award because of all the lobbying involved,” says Rangarajan.

Poet and writer Ilango Krishnan believes that the present controversy is not about the quality of the book or the translation, but the way it has been chosen.

“Maalan is associated with the Akademi in one of its committees. There were three jury members who selected his work. Of the three, two were his friends. That is what is problematic. Maalan should have rejected the selection or refrained from participating. He should not have accepted the award,” Krishnan says, adding that the controversy doesn’t discount Maalan’s other contributions to the field of media.

“It is only the role of lobbying in Akademi awards that the current controversy has highlighted.”

Tamil Sahitya Akademi – a history of backscratching and backstabbing

The Sahitya Akademi was founded in 1954 and the Tamil edition started awarding writers in 1955. The first ever Sahitya Akademi Award for Tamil was won by author RP Sethu Pillai for a series of essays. Interestingly, Pillai was a member of the Akademi’s advisory board since 1954.

“When he was awarded, many from within the board objected to the decision because Sethu Pillai was Akademi’s own member. But writers like Kalki Krishnamurthy welcomed the decision of the Akademi. Surprisingly, the very next year, Kalki was chosen for the award,” says Ilango Krishnan.

The current convener of Akademi’s Tamil advisory board, poet Sirpi Balasubramaniam, himself was awarded by the Akademi twice for translation in 2001 and a poetry collection in 2003. That too created a controversy. What’s more, his friend Puviyarasu has also been awarded in the same manner in 2007 (for translation) and 2009 (for poetry collection).

“These two were active in Vanambadi, a literary movement founded in Coimbatore in the 1970s. Along with them, Kovai Gnani, a Marxist scholar, had also made immense contributions. But when Balasubramaniam entered the Akademi, due to his personal differences with Gnani, the latter was not considered for an Akademi award,” he adds.

If one looks at the list of writers who have won the Akademi from its inception, it shows most of the writers were from the Brahmin community and male writers. In 1990, when writer Su Samuthiram, belonging to a backward class, won the award, the Tamil literary world was rife with criticism “whether reservation has been introduced in literature as well”.

Sa Kandasamy, an Akademi winner who died in 2020, had also expressed displeasure over the all-pervading lobbying culture. In a conversation with this correspondent a few years ago, he narrated an incident when writer Jayakanthan, who was a member of the jury, once told Kandasamy that his novel was not selected for the award in that particular year because another woman writer requested Jayakanthan to select her work instead.

While on the one hand it is alleged that the Tamil Akademi is mostly controlled by the dominant community members, it is also claimed that most of the jury members are from the Tamil Nadu Progressive Writers & Artists Association (TNPWAA), a cultural arm of the CPI(M).

Talking to The Federal, writer Aadhavan Dheetchanya, who is also the general secretary of TNPWAA, says even if one goes by the above claims, only four or five writers associated with the Communist ideology have won the award in the past 67 years.

“There is a need for rotation in the advisory boards and selection of jury. Besides, the process of selecting books is also obscure. For instance, 53 novels were published in Tamil in 2021. When it comes to the TNPWAA, our jury reads all those 53 novels and then shortlists the books. But is such a process in place in the Akademi?” he asks.

“How many works have been considered by the Akademi? Does it give an award to a particular book or translation work based on the writer’s literary contributions in their lifetime, or do they give awards only to works published in that particular year?”

According to Deetchanya, fixed tenure for members and changes in the selection of jury could help change things and foster a culture of integrity.

“As a rule, the jury should have at least one Akademi award-winning writer. There is a possibility that these writers can influence the jury and push them to select a writer who may be their friend or relative. So, such rules don’t help much. Instead, even young authors who have never won the Akademi award can be included in the jury,” he says.

Ilango Krishnan adds that the reason the problem persists is because even Akademi award-winning writers are not coming forth to criticise the much-apparent ills.

Krishnan and others like him insist that it is the problems plaguing the system that are being criticised, and not Maalan’s work.

Maalan – A media icon

Maalan, born as Venket Subramanian Narayanan, in Virudhunagar district’s Srivilliputhur, burst onto the Tamil literary scene when he was barely 15 through Ezhuthu magazine. At first, he started penning poems. He then explored other formats such as short stories, essays and novels.

He kicked off his career as a journalist with Thisaigal, the first youth magazine in Tamil, founded by renowned journalist and author S Viswanathan, who was widely known as ‘Saavi’. The magazine claimed to be a platform for the youth and by the youth. It was the first magazine to introduce ‘student journalists’.

In his late 20s, he became the editor of the magazine and nurtured many who later went on to become popular journalists such as AS Panneerselvan, the former Reader’s Editor of The Hindu, Sudhangan, the first Tamil journalist to win the Statesman award for best rural reporting, writers such as Pattukkottai Prabhakar besides painters and filmmakers like Aras and Vasanth S Sai.

Maalan later worked as editor of Dinamani, India Today (Tamil), Kumudham, Kungumam, Puthiya Thalaimurai and as well as the Sun TV.

(Disclosure: Puthiya Thalaimurai is a sister concern of The Federal.)

As a writer, he has more than 20 books to his credit. His work Jana Gana Mana, a novel set in the aftermath of the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi and published in 1990s, later became the base for Kamal Haasan’s Hey Ram (2000), as claimed by many. His title of a column, En Jannalukku Veliye (Outside my window), published in various magazines at different points of time, has become a catchphrase in media circles.

Of late, he has been criticised for some of his views which in most instances support the right-wing narrative. Speaking to The Federal about the controversies surrounding him, he says the Akademi is not being awarded based on the writer’s political inclination or ideology.

“There are three stages in selecting a book for the award. In Ground List, the first stage, about 30 people from various walks of life such as academia, librarians, litterateurs would recommend two books each. Then a preliminary panel comes up with a list of five books. None of the members from the general council, executive board or the advisory board can become a part of the panel. The jury members are directly appointed by the Akademi chief. The appointment of the jury remains a secret to the extent that none of the members from any board know who the jury members are. After the selection, the chief would announce the award with the permission of the executive board. Finally, the award is only for the book,” he says.

According to Maalan, there have been precedents when some of the general council members have been awarded in the past like Shashi Tharoor (English), Veerappa Moily (Kannada) – both from the Congress – Imayam (Tamil), a DMK functionary, Su Venkatesan (Tamil), a CPM leader and Lok Sabha MP. He also insists that caste doesn’t play any role in handing out these awards.

Whether what Maalan says is true or not, one thing that his critics strongly believe is that the Akademi is certainly not an open book nor are the goings-on within the hallowed walls.

“There is an urgent need for transparency,” says writer Aadhavan Dheetchanya. Great works of literature, he adds, need light to shine.