- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Why India is banking on nursing mothers to save preemies

Namitha, a mother in her 20s, has been donating her milk to the human milk bank at the Kanchi Kamakoti Childs Trust Hospital, Chennai, ever since the birth of her daughter. Her daughter, a preemie, is in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of the hospital. Namitha pumps milk to feed her daughter, and the excess milk expressed by her is stored at the milk bank. “I want to continue...

Namitha, a mother in her 20s, has been donating her milk to the human milk bank at the Kanchi Kamakoti Childs Trust Hospital, Chennai, ever since the birth of her daughter. Her daughter, a preemie, is in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of the hospital. Namitha pumps milk to feed her daughter, and the excess milk expressed by her is stored at the milk bank. “I want to continue donating to the bank, even after my discharge from the hospital. There are many preterm babies like mine that can benefit from my milk. As a mother, I feel it is my responsibility to help them,” she says.

- History of milk banks

- The concept of milk banks stems from the practice of wet nursing

- The first human milk bank came up a century ago in 1909 in Vienna, Austria

- India was the first Asian country to set up a milk bank, in 1989 at Sion Hospital in Mumbai

- Brazil has the strongest network of milk banks with 217 banks

Not far away is the Institute of Child Health and Hospital for Children (ICH), a state government facility, which was the first to have a human milk bank in Tamil Nadu in 2014. Mothers like Nisha Rajagopalan have been helping infants by donating their milk periodically. Nisha, who has been delivering her milk to the hospital for the past three months, says, “I heard about human milk banks from a friend in the United States. When I had my second child a few months ago, I began using a breast pump to express milk quite early. I decided to donate the surplus milk after consulting my paediatrician and chose the ICH because it has newborns who are abandoned and infants who do not have access to mother’s milk.” Nisha has donated as much 16 litres to the bank in the past few months.

Banking on mothers

Human milk banks should be an integral part of the health system, say doctors. According to a WHO report, of 27 million births in the country, as many as 3.5 million are preterm births (or before 37 weeks of gestation are complete). Dr Deepa Hariharan, a paediatrician-neonatologist based in Chennai, says that most preterm deliveries happen at hospitals without NICUs.

“The babies have to be separated from their mothers and admitted to facilities with NICUs. Early initiation of breast milk becomes a practical challenge. In C-section deliveries due to high rates of gestational diabetes and pregnancy-induced hypertension, the pain after the procedure also makes it practically difficult for them to express milk. Most preterm babies need intensive care or are on oxygen support with IV fluids. In both cases, the infant should be fed breast milk within one hour of delivery, but it hardly happens. Mother’s milk is packed with antibodies and no formula or other forms of milk can be a substitute. Therefore, human milk banks are important to provide nutrition for the newborns,” explains Dr Deepa. She adds that a mother starts to secrete less milk with emotional and physical separation from the baby.

There are infections like necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), a condition where a portion of the bowel dies, that typically occur in newborns that are either premature or otherwise unwell. “Mother’s milk is extremely helpful to avoid such a condition,” says Dr Vanathi Vijayakumar, neonatologist, Kanchi Kamakoti Childs Trust Hospital. Dr Vanathi adds that rising fertility issues among couples who go for IVF and other treatments have led to a higher number of twins or triplets. “The mother is unable to meet the needs of two or three babies at a time. For them, such milk banks are extremely helpful,” she says.

When asked why she donates milk to someone else’s baby, Vijayalakshmi, mother of a one-year-old, says she wants to help preterm babies who do not have access to mother’s milk. “My decision was met with stiff opposition at home, but I do all that I can to save the babies at the NICU. I go to the ICH once a month to donate my milk. I will do it as long I have excess milk.” She now encourages other mothers to do their bit. “Mother’s milk is the best food for a child. When I see mothers struggling to feed their child, I want to help them out.”

How they operate

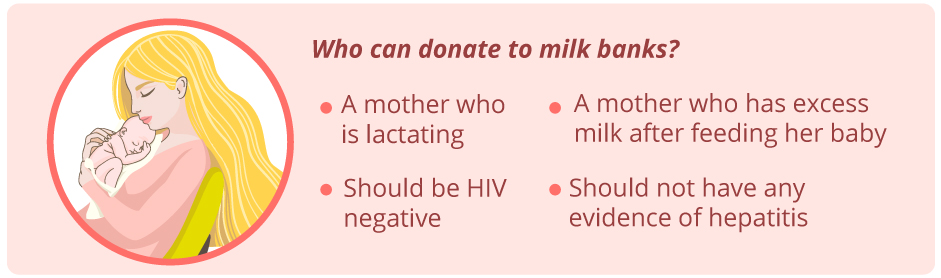

Human milk banks collect milk pumped and stored in bottles from mothers either from hospitals or from the community. Says Dr CN Kamalarathnam, professor and head, Department of Neonatology, ICH, “The milk is also collected from lactating mothers who visit the outpatient ward for their checkup. The collected milk is screened for infections and then pasteurised, frozen and stored for upto six months.”

These banks work largely on word-of-mouth communication on the need to donate excess milk. Koushalya Jagadeesh, a lactation consultant who is a donor herself, says, “I decided to donate after I received help from a donor mother for my son following a C-section delivery. I began donating soon after I started expressing milk.” Koushalya has been conducting drives every month among mothers visiting the ICH to meet the needs of the hospital.

While ICH caters to the needs of the babies at its facility, there are private hospitals like Kanchi Kamakoti Childs Trust Hospital that contribute to other hospitals as well. Dr Vanathi explains, “The milk is free of cost and our bank is largely driven by volunteer mothers.” The hospital has had over 300 donors and collected about 4 lakh ml of milk from across the city.

Inaya Foundation set up the first milk bank in the northern region of the country in Rajasthan. Nitisha Sharma, founder secretary of the foundation, which set up the ‘Vatsalya – Maatri Amrit Kosh’ milk bank at the Mahatma Gandhi Hospital in Jaipur in 2016, says, “We have a child specialist and a counsellor who talk to the mothers to persuade them to donate excess milk to the bank. The milk collected and stored is shared with private and government hospitals.” Inaya is in talks with facilities in other states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar to set up similar banks.

Paid milk banks like Amaara, which is located in Delhi-NCR and Bengaluru, sell a 150 ml bottle of milk to hospitals for ₹200. An initiative by the Breast Milk Foundation, it primarily meets the requirement of low birth weight babies (under 1.5 kgs) in NICUs. “The two banks, in Delhi and Bengaluru, cater to hospitals and milk is provided free of cost for babies from below poverty line families. Through repeated campaigns on social networking sites like Facebook and Twitter, we have been able to bring in donors and some of them are repeat donors,” says Ohika Chakraborty from the foundation.

Need for more

There are about 60 milk banks in the country, but this is far from enough, say experts. Take the case of Tamil Nadu, which has about 18 in the government sector. Hospitals like ICH face a shortage of milk since they don’t rely on other banks for help. “We need 1,500 ml on a daily basis, but we are able to access only 1,200 ml. We are looking to scale up operations. PATH, an organisation focusing on milk banks, will be collaborating with us to achieve this,” says Dr Kamalarathnam.

The need for milk banks points to the need for better breastfeeding practices among new mothers, says Dr Jayashri Jayakrishnan, lactation consultant, Fortis Malar Hospital. The National Family Health Survey-4 reveals that only 56 per cent of mothers in India practise exclusive breast feeding. To change this, people like Koushalya have been conducting sessions with the women to ensure that they breastfeed. “They should start breastfeeding at the earliest, even if the babies have been dependent on milk banks. They should not switch to cow’s milk or formula once they are out of the hospital,” she says.

Such counselling has brought about a transformation at Mahatma Gandhi Hospital, says Nitisha. “Over time, we have eliminated mothers’ dependence on substitutes. Mothers at the hospital have adopted breastfeeding from the beginning and this is due to the constant interaction with the counsellors at the centre.”

The Centre has been batting for the scaling up of milk banks through the formulation of the National Guidelines on Lactation Management Centers in Public Health Facilities in 2017. PATH, a global organisation, collaborated with the government to come up with the guidelines that look at supporting expression of the milk.

Ruchika Sachdeva, deputy director, Maternal, New Born, Child Health and Nutrition, PATH, says that mother’s milk can save neonates. “The number of neonatal deaths below 28 days has increased, even as we have brought down deaths under the age of five. Mother’s milk can save these lives. The guidelines formulated by the Centre aims to support the Comprehensive Lactation Management Centre in the states through the National Health Mission by bridging the gap between breastfeeding and banking of milk. The model proposed by the government aims to bring about interventions at various levels where milk collected at smaller facilities can be stored and preserved at the mother facility across regions.” Ruchika adds, “The good thing is that at least 50 of the 60 milk banks are in the government sector.”