- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

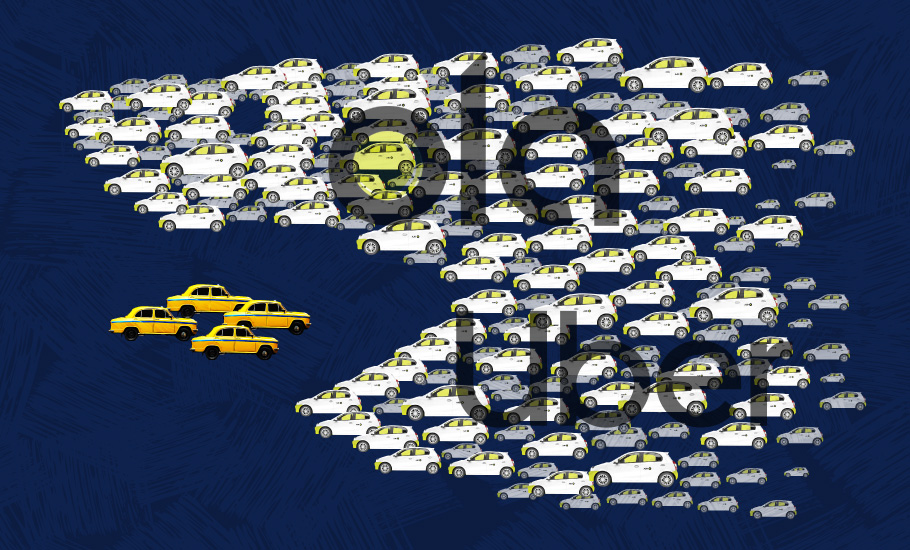

Tech monopoly, exploitation drive smaller players into despair

Big tech companies are dictating terms to customers, partners and also the government, even as they kill the competition by smaller players and garner a larger part of the revenues.

In a shocking incident on March 30, Prathap Kumar, a 34-year-old airport taxi driver attached to Karnataka State Tourism Development Corporation, died by suicide after setting himself ablaze inside his car in front of the departure and arrival gate outside the Kempegowda International Airport in Bengaluru. Kumar parked the vehicle in the middle of the road, closed the windows, and doused...

In a shocking incident on March 30, Prathap Kumar, a 34-year-old airport taxi driver attached to Karnataka State Tourism Development Corporation, died by suicide after setting himself ablaze inside his car in front of the departure and arrival gate outside the Kempegowda International Airport in Bengaluru.

Kumar parked the vehicle in the middle of the road, closed the windows, and doused himself in petrol. By the time an onlooker tried to help and the fire service came to his rescue, Kumar had sustained 70% burn injuries and died in hospital the next day.

His fellow drivers at the airport say Kumar was upset over low earnings and had a bank loan of nearly ₹4.5 lakh to repay. With infrequent trips and customers preferring Ola and Uber over state-run taxis, Kumar and others were losing out on income.

Ramesh Gowda, president of Kempegowda International Airport Taxi Drivers and Owners Welfare Association, says Prathap had to wait for 18 hours to get a single ride.

“Sometimes he returned home without any ride. Which meant he earned no money for the day. He came to the city with big dreams. More than the pandemic, the unfair competition killed him,” Gowda says.

After his death, the state government announced an ex gratia of ₹5 lakh, which his family members say they are yet to receive.

“Had the government woken up to implement our suggestions to have digital taxi meters installed in all Ola, Uber cabs, things wouldn’t have turned this worse,” Gowda adds.

With nearly 3,000 drivers staging a strike, the state government immediately raised the base fares charged by taxi drivers and aggregators.

The taxi drivers’ association has long been demanding the government to enforce a single metering system, like in autos, so that the price remains uniform across the board. But drivers allege the aggregators reduce the prices to woo customers, kill the competition and dominate the market.

Prathap’s suicide was also a fallout of the COVID-10 pandemic. The lockdown rendered taxi drivers jobless and later, with few orders. Add to it the high price of fuel, along with the unfair competition by cab aggregators, it was a death knell for many.

Tanveer Pasha, president, Uber, TaxiForSure and Ola drivers and owners’ association, says cab services run by KSTDC, Megha, and Meru, who were completely dependent on airport customers and charged ₹21 per km, lost out to Ola and Uber which offered rides at ₹9 or ₹10 per km.

“With soaring petrol and diesel prices and toll and parking charging, how can one operate at ₹10 and sustain,” Pasha asks. “There has to be a uniform pricing structure.”

The prices fixed by the Karnataka Government for cab aggregators and other taxi operators, effective April 1, 2021, were divided into four categories-A, B, C, and D, depending on the cost of the vehicle. Say for category C, for vehicles that cost ₹5–₹10 lakh, which most cab drivers use, the base fare was fixed at ₹100 for 4 km and thereafter a minimum price/km—₹21—and maximum price/km—₹42.

Gowda disagrees with this formula, saying price ranges cannot be 100% higher.

“We cannot protest against the government because there are COVID restrictions. We cannot protest against the company because they will blacklist us. What can we do?” he asks. “KSTDC does not even have a customer care service. So how can we solve disputes and air our concerns if the government deliberately shuts its ears.”

Most of these drivers are left to manage on their own, with no support from the companies. The UK Supreme Court in February ruled that Uber’s drivers were entitled to workers’ rights and should be treated as employees, following years of legal battle with the Silicon Valley-based taxi-hailing service.

On a similar petition in India in 2017, the Delhi High Court ruled that the relationship between drivers and companies was ‘purely contractual’, which limited their benefits. While the courts in the US and UK sided with the drivers, in India, the drivers were let down.

The rise of the tech industry and startup ecosystem in India post-2010 ushered in the growth of online cab aggregating companies like Ola and Uber, which attracted not just tech talent from the IT companies, but also drivers (driver-partners as they are called) associated with those companies. Many switched jobs to become self-reliant.

Lucrative income, hefty incentives and affordable loan schemes made drivers move from villages and smaller towns to Tier 1 cities like Bengaluru, Delhi Chennai, Hyderabad and Mumbai.

Coupled with cashback and discounts, they used technology to reach millions of people at the touch of their phones, in the otherwise unorganised market.

However, as more and more drivers joined in with new cars, the cab hailing business did not boom at the same rate, forcing quite many to leave the profession.

Over the years, drivers have been crying overexploitation by taxi aggregators and complained of fall in incomes, not what the companies promised.

On several occasions, drivers in various cities took to the streets demanding higher incomes and government regulation, but all fell on deaf ears.

The Federal in 2019 reported how the joy ride for Ola, Uber drivers was over. The tech companies slashed driver incentives, brought more cars on the road to meet the growing demand. And the pandemic only worsened their conditions. Drivers reported a 70% drop in income compared to the highs in 2014-15.

The digital economy, with innovation driving the economy, no doubt offered better access and cheaper products to consumers. But it also facilitated the growth of unhealthy competition and concentration of market forces in the hands of a handful of players.

Be it in the e-commerce sector by Amazon and Flipkart, or with news aggregation by the likes of Google and Facebook, or with cab-hailing services by Uber, Lyft, Ola and others, tech companies are wielding more power than before. They are dictating terms to their customers, partners and also the government, even as they kill the competition by smaller players and garner a larger part of the revenues.

The Confederation of All India Traders (CAIT) secretary general Praveen Khandelwal says the retail industry has been deeply affected by deep discounting, capital dumping, exclusive seller agreements, with lack of a level playing field.

“The growing contraventions by these entities, that too during the pandemic, are targeted to completely uproot the domestic retail sector in India,” Khandelwal says.

As big tech companies wield monopolistic influence over the supply of digital services and capital, a regulatory framework should ideally help in bringing a level playing field. But analysts say governments too face a big challenge.

In October 2020, US lawmakers after a 16 month-long investigation, in a report said Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google, exercised and abused their monopoly power. They called for sweeping changes to antitrust laws in the country.

Lawmakers said the companies turned from “scrappy” start-ups into “the kinds of monopolies we last saw in the era of oil barons and railroad tycoons,” New York Times reported.

The report highlighted how the companies abused their dominant positions and dictated prices and rules for commerce, web search, advertising, social networking and publishing businesses.

In February, the tech giant Facebook’s ban on Australian news cut off vital sources of information for the Pacific region. The tech giant wiped all news on the platform in Australia in response to a legislation that mandated Facebook to pay for content from media groups. Later the company however signed deals to pay the new publishers.

On April 10, China slapped a record $2.8 billion fine on Alibaba Group Holding Ltd, following an anti-monopoly probe that said the company abused its market dominance. This comes as the Chinese government clamped down on tech giants.

“Imagine tomorrow if Google says it will stop the map services in India. Some of the transportation services will come to a grinding halt. Many may not reach the desired destinations. There will be chaos all across,” Harish HV, managing partner at Ecube Investment Advisor says. “It’s not a good thing that the smaller players are making losses and not able to sustain. But the regulatory framework should be put in place before letting these businesses thrive. Else they will become so dominant to dictate terms,” he adds.