- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Silk rout: COVID, Chinese imports take the shine off Indian silk

About 50 km from Bengaluru, on the way to Mysore, lies the Ramanagara silk cocoon market, one of the largest in Asia. Farmers from across Karnataka gather here to sell their produce through a bidding process. They arrange the cocoons in the bins allocated, as per different grades and qualities. Reelers who reel the cocoons together to produce silk threads arrive at the same time to inspect...

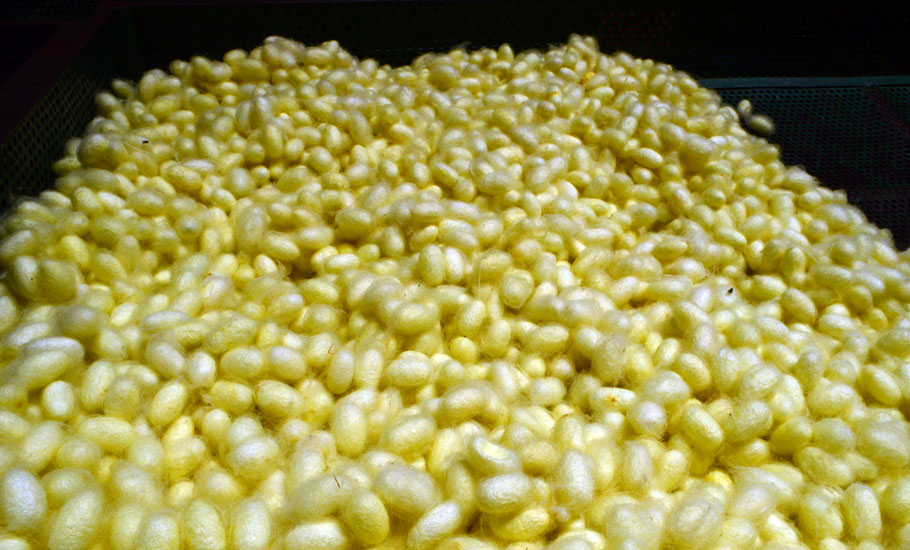

About 50 km from Bengaluru, on the way to Mysore, lies the Ramanagara silk cocoon market, one of the largest in Asia. Farmers from across Karnataka gather here to sell their produce through a bidding process.

They arrange the cocoons in the bins allocated, as per different grades and qualities. Reelers who reel the cocoons together to produce silk threads arrive at the same time to inspect the texture and colour.

However, this time, the farmers realise that the market conditions are not good as the price has been continuously dropping since the COVID-19 lockdown was imposed. Low demand for textiles has led to around 60-70% drop in price in three months. The average price per kg of cocoon (cross breed) used to be ₹450-480. Now it is ₹150-160 per kg.

The bivoltine hybrid cocoons, a higher quality mulberry silk produced in India as an import substitute, traded a bit higher at ₹220 per kg in Karnataka. In neighbouring Tamil Nadu (Dharmapuri market), it fetched an even lower price, around ₹170 on July 20.

Hemanth PR, 33, a second generation farmer in Ramanagara whose family has been cultivating mulberry leaves and producing cocoons for over three decades now, says this is the steepest price fall that he has seen in a decade. Hemant cultivates mulberry leaves in one acre of land and produces about 150 dfl (disease-free layings) that can fetch 140 kg of cocoon every two months.

“To produce 100 dfl, it cost us ₹10,000, including the farm labour, without adding the costs of self-labour and water charges. If we include that, our cost could go up to ₹17,000,” he says.

At the current price of about ₹150 per kg, his profits would be around ₹4,000 after two months of work, or ₹2,000 a month. It reflects the scenario of a small and marginal sericulture farmer in the region.

However, this meagre profit is due to his location. Hemant resides in Ramanagara. For other sericulture farmers who had come from districts like Tumakur and Mysore, the transportation cost eats up the little profit they make and they return with a forlorn look on their face.

HL Ravi, a farmer from Kolar who sells just mulberry leaves to cocoon rearers, says he sold one-acre produce at ₹50,000 when the market was at its peak. Today, he finds no buyers, and if someone is willing to purchase, the rate is ₹18,000. “I am thinking of quitting mulberry cultivation and resorting to sheep rearing,” he says.

Many farmers either undertake vegetable or dairy farming along with mulberry cultivation to eke out a living.

Chain effect

Although India does not export raw silk, the fabrics and readymade garment export account for 80% of the export revenue. India earned ₹2031.89 crore in 2018-19 from the trade, down from 2093.42 crore in 2016-17. Countries like UAE, US, UK, China and a couple of African countries were the leading buyers of Indian silk products.

South India contributes 60% of the raw silk production in the country. Karnataka alone accounts for a third of the country’s total production. States like West Bengal, Jharkhand, Assam and Meghalaya contribute another 30%, as per data from the ministry of textiles.

The weak demand is a chain reaction—if consumers do not buy silk products, the weavers do not buy silk yarns from reelers and this results in reelers paying a low price to cocoon rearers and farmers.

Now even the reelers are in hot water. With no orders, the unsold raw silk and silk yarns have piled up and they are neither able to pay the farmers nor take any fresh orders. Mohammed Muheeb Pasha, president of Karnataka State Silk Reelers’ Association, estimates that nearly 7,000 reelers in the state produced nearly 2,500 tonnes of raw silk, all of which lies unsold.

Weavers in Varanasi, famous for Banarasi silk sarees, said weak demand from cloth merchants and customers had stalled production. “With job cuts and pay cuts all across, and with malls and establishments largely remaining shut, we have no fresh orders for silk sarees. So we are not buying yarns,” says Ram Lal Maurya, a weaver in Varanasi.

Ram Lal says he produced sarees costing ₹5,000-70,000, before the lockdown, but since then there’s been absolutely no sales. “Many small scale units are shutting down in town,” he says.

Ban Chinese imports?

But besides the poor market conditions, there’s another issue that is a cause of worry for—the import of cheap raw material from China.

Usually, the adverse climate, pest and disease incidences affect cocoon production, quality and price but in this downturn, imports from other countries, especially China, are further dampening conditions for local farmers.

While the domestic bivoltine yarn usually costs ₹4,000-4,500 for 10 kg, the Chinese yarn comes at ₹3,500 onwards. With the current downtrend, the Indian ones are sold at ₹2,400 as of July 20 while the Chinese ones come at ₹1,800.

China is the largest producer of silk in the world. It accounts for nearly 75% of the total 1.6 lakh metric tonnes of silk produced globally, while India accounts for about 20%. So China dominates the world and they produce in excess. China dumps the excess produce to India at a cheaper rate.

But when there’s a chorus across the country for a ban on Chinese products, silk weavers are against it as they are highly dependent on cheap Chinese imports of raw material. This goes against the local sericulture farmers, who believe they would fetch a better price for their produce if Chinese imports are banned.

“Usually the market price of Chinese yarn reflects on the price here (within India). With weak demand, the price has already hit rock bottom. If the government does not ban it, weavers will buy more cheap Chinese silk, it will kill our market,” fears Hemanth, the farmer from Ramanagara.

India has shown a rise in silk production over the years, but it is heavily dependent on raw silk and silk yarn imports from China and Vietnam. Although the raw silk imports have come down steadily from 5,683 MT in 2011-12 to 2,785 in 2018-19, nearly 80% of those imports comes from China and Vietnam and accounts for a ₹1000 crore market. Natural silk yarn and fabrics account for another ₹300 crore.

Experts suggest that this is the right time for the country to ban Chinese silks that have played havoc in strangulating a struggling domestic sector. The Karnataka government, the Khadi and Village Industries Commission (KVIC) and sericulture universities in the country have urged the Centre to impose a ban on Chinese silk or hike customs duty so that the imports are controlled. For the last three years, the customs duty on mulberry raw silk was 10% while for silk fabrics, it was raised to 20% in 2018-19 from 10% earlier.

Buy Chinese, say weavers

Weavers, however, say that Chinese silk, which is 10-15% cheaper, is also good in quality, and hence the higher dependency.

And because of that, the Benarasi silk saree has gotten a different shine and no longer has the heaviness that came with pure zari.

“The Chinese threads are light in weight, more glossy and rich in colour unlike the Karnataka (India ones) which are heavy, thick which makes them difficult to weave in mechanised units,” says Mohamed Ishaq Ansari, a weaver in Varanasi. “The Georgette silk varieties are only available from China. We cannot use the South Indian silk yarns for it,” he adds.

Agreeing with Ansari, Maurya says though the price difference between the Indian and Chinese silk differs by ₹500, quality matters for them. “A ban would completely stall business,” Maurya said.

While the Mysore silk sarees, Ilkal, Kancheevaram, Dharmavaram and Banarasi sarees, all have a shade of domestic silk, the reliance on Chinese silks has made them lighter and cheaper.

Can we do away with Chinese imports?

“It’s not that Chinese imports are putting us in a bad spot. We procure more from China as the domestic production is not enough and does not match the export quality,” says Dr RN Bhaskar, professor of sericulture at University of Agricultural Science, Bangalore. “We get 20-30% higher price on the finished goods in the export market as most of them have Chinese inputs.”

A source at the Central Silk Board said India was importing more than the agreed quantity from China.

But professor Bhaskar says we do not have the technology to produce the fine breeds. He says even if the government gives subsidies to farmers, many do not come forward as they are stuck with cross breed variety for decades. He opines that we cannot ban Chinese imports as it would kill the silk weaving industry.

“Farmers are unwilling to produce bivoltine varieties which are rich in quality as they fear that it would not perform well due to climatic conditions here,” Bhaskar says. “That’s just a moral fear. People from Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, which are in the second line of production, are pushing for bivoltine variety. We (Karnataka) need to pick up pace.”

Despite key politicians of Karnataka, including former ministers such as DK Shivakumar, DK Suresh, CP Yogeshwar and former chief minister HD Kumaraswamy, representing constituencies having rich sericulture production, farmers say the leaders have failed to address their concerns on Chinese imports which they’ve been raising for the past decade.

Besides, sericulture promotional bodies complain of lack of funding for researching products on sericulture based activities. Unlike in China, the Indian market for cocoon and yarn production is not well organised. Also, China has a well mechanised industry which gives a standardised and rich quality whereas India is still dependent on manual labour.

“China has nearly 200 varieties of cocoons while we barely have five. If there are enough funds, we can research and take it to the market,” says Dr HB Manjunatha, professor and chairman, department of sericulture studies, University of Mysore.

Manjunatha feels China is monopolising the Indian market and they are working towards destroying the opponent (India). “They have paralysed this sector. Unless we develop indigenous varieties and spend more on research, it is tough to reduce the import dependency. But I feel this is the right time to bring that change,” Manjunatha adds.

Sericulture farmers like Hemant still hope for a better deal so that they can at least recover the cost of production if they are unable to earn any profits.