- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

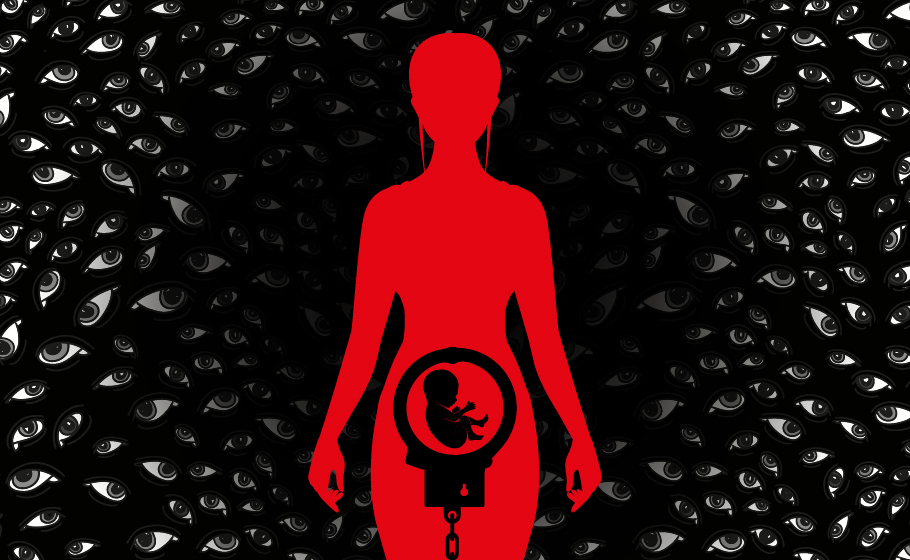

In 'sanskari' India, abortion continues to be a big deal

When Girish (name changed) and his partner approached a gynaecologist for abortion at a renowned multi-specialty hospital in Chennai, he was horrified at the reaction. “She [the doctor] asked if we were married. When we said no, she said she won’t perform [the abortion] without a husband or parents of the woman being there.” While gynaecologist clinics should be spaces where women...

When Girish (name changed) and his partner approached a gynaecologist for abortion at a renowned multi-specialty hospital in Chennai, he was horrified at the reaction.

“She [the doctor] asked if we were married. When we said no, she said she won’t perform [the abortion] without a husband or parents of the woman being there.”

While gynaecologist clinics should be spaces where women seek counsel and medical assistance free from guilt and shame, that is often not the case. In fact, many gynaecologists while noting the sexual history, often start with ‘Are you married?’, instead of asking, ‘Are you sexually active?’, making their clinics hostile spaces for women.

Such judgmental medical practice makes abortion-seekers opt for other methods, including risk-heavy procedures, done outside the supervision of trained medical professionals and ill-informed self-medication without a prescription.

The numbers are horrifying. About 73% of all abortions are done outside of health facilities, according to a study published in The Lancet health journal, which estimated that there were 15.6 million abortions in India in 2015. Four years since then, even though under-reported, the numbers are likely to have increased.

The same study noted that about 5% of all abortions or 0.8 million are not surgical or medication-based and are done through unsafe methods such as inserting a stick or roots, herbal medicines. An estimated 13 women die every day because of unsafe abortions practices.

But despite huge demand, the abortion market in India runs significantly on ‘supply-side’ economics. Most abortions are carried out in expensive private clinics or through self-medication. Subsidised and free of cost public health facilities are either short-staffed or not fully functional. Institutional accountability seems like a utopian dream, and most insurance policies do not cover even voluntary abortions. Stigma, shame and stereotypes ensure that the ‘demand-side’ stakeholders of this issue — women who seek abortions — find it difficult to demand better services.

The insistence that women’s sexuality must be linked with marriage takes an ugly form when doctors insist on getting consent from those other than woman who wants an abortion whereas the law requires only the woman’s consent if she is above 18 years of age. A guardian’s consent is required if she is younger, but otherwise, the woman’s parents or husband or others have no legal say in her decision to go for an abortion. There is no clause obstructing any woman, married or not, from seeking an abortion.

Marriage and sanction

The term ‘pre-marital sex’ suggests that a person should ideally become sexually active only after marriage. However, even the legitimacy of marriage wasn’t enough to help Varsha (name changed), a 30-year-old advertising professional, who wanted an abortion.“My doctor had initially refused. Said I’d change my mind about this [abortion], even though I clearly told her I have physiological, economical, philosophical and emotional reasons to not want a child. The doctor, who was in her early 30s, then asked me to leave the room so she could speak to my husband privately. When that didn’t work, she refused to carry out the procedure until my mom flew down and tried to convince me. I was desperate so had to put up with all this.”

Finally, Varsha had an abortion through a vaginally administered pill. “She didn’t tell me what would happen. Just put the pill and told us to leave. I took six steps out of the hospital and collapsed with crippling pain. I didn’t know if this was normal or not because she didn’t tell me what would happen.”

Such incidents are not rare.

Doctors and dogmas

It all comes from the life-long conditioning in patriarchal values, stereotyping of gender roles, slut-shaming, societal ridicule and ostracisation that have kept women within suffocating ‘lakshman rekhas’. In Indian culture, women are considered ‘ghar ki lakshmi’ (goddess of the house), and this is the basis of the patriarchal system in the society wherein the woman’s fertility is controlled to ensure that caste and class lineages can carry on without any ‘impurity’ arising out of individual choices made by her.

Married women are shamed for not wanting a family. Unmarried women are shamed for being sexually active. If neither, then abortion-seeking women are shamed for killing a ‘life’, without realising that the ‘woman’ is a life too. Instead of being seen as individuals with rights and dignity, women are seen as mere vessels for carrying and nourishing a man’s child.

Doctors are expected to be the source of credible information, unbiased advice and medical/surgical service. Yet, doctors are not created in a vacuum nor are they immune to personal biases and opinions, societal taboos and their own indoctrination and conditioning. Instead of sound, reliable information on sexual and reproductive health and rights, women are dependent on nuggets from friends and elderly women. Sex education in India is only beginning to catch up, and that too, inadequately. Even the internet can’t fill this void since more often than not random Google searches can easily provide conflicting and confusing information.

Is there a solution?

A multi-layered problem needs a multi-faceted solution where all stakeholders are involved. Policy-wise, one solution is to increase the number of trained and certified doctors for conducting abortions. Increasing the ambit and including health professionals other than doctors can reach more women through public health facilities would also help. For example, the Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) workers are often the first point of contact for many rural women’s reproductive concerns.

Next, the ability of government health centres to carry out abortion services should be increased by addressing the lack of necessary equipment and training.

When India established the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act in 1971, only three other countries in the world had liberal abortion policies. However, like many other well-intended government policies, this one too has become outdated and scarred by corruption, bureaucracy and government apathy. There is an urgent need for institutional accountability for private health practitioners.

Also read: Rape victims can end pregnancy sans medical board nod: HC

It is also necessary to look into how the number of abortion-necessitating pregnancies can be reduced. Ultimately, planned abortions are an end to unplanned pregnancies. In fact, of all the pregnancies in India, nearly half are unintended or unplanned. And unplanned pregnancies result from avoidable and unavoidable causes. Contraceptive failures, inherent to all birth-control methods, count as unavoidable causes. Avoidable causes are many and include the unmet need of information on contraceptives, cases of rape, and reluctance of men in birth-control participation.

“You don’t need to be a medical professional to know that men have it easier than women in family planning,” says Dr Sharfaroz, a physician who has practiced in Andhra Pradesh. He explains that when you take the temporary and easy-to-use options available, doctors have a low success rate in convincing the husbands to use a condom for family planning. So, they end up prescribing pills for women, which often have side-effects that are worse with long-term use.

“Men are offended that they are asked to wear condom that women get back from public health centres. So, their wives ultimately pay the price. For relatively permanent methods of contraception, it is well-established that vasectomy for men is easier and safer than tubal ligation for women. But men think it emasculates them and there are myths of impotence from it, which are total rubbish,” he says.

On the other hand, when contraception fails, women often opt for over-the-counter emergency contraceptive pills (ECPs). In cities like Chennai, institutional patriarchy has resulted in an unofficial ban on emergency contraceptive pills in several places. Vaishnavi Sundar, a filmmaker from the city, who ran an online petition towards this cause, says, “It’s been three years since the ban was lifted but availability is still a systematic problem. Individual pharmacy stores can take the liberty to circumvent an actual legal order to sell a schedule H drug over the counter only because a woman’s morality is tied to it. Such a problem will never arise for Viagra, which is sold aplenty.”

When asked why she didn’t raise a complaint with hospital authorities, Varsha said the whole process had drained her out, and all she wanted was for things to get back to normal. “I wish the hospital gets listed in some ‘to-avoid’ list rather,” she says.

But can a cautionary list ever be a solution to this multi-layered problem? Perhaps. When faced with an uncooperative gynaecologist, Girish found the solution on Practo, where he and his partner found another doctor. Internet age has allowed for publicly visible user reviews to ensure that doctors behave and hospitals hold them accountable.

When institutional mechanisms fail, women often form their own whisper network. One such network is ‘A Crowdsourced List of Gynaecologists We Trust’, which has details and reviews of doctors based in 23 cities. Women keep reviewing and adding more information to it to help their unknown anonymous sisters.

According to one woman’s account from the same list, the doctor she approached in Pune was the “most respectful and supportive of her choice to not have children”.

“There was no judgment and no censure in her tone or behaviour. She also advised against certain birth control [methods] based on my own health issues and recommended that the onus of birth control be on me and my partner jointly. She is a gentle and kind person and has always made me feel comfortable.”

While the wait continues for states and institutions to do their bit, feminist practices of sisterhood — such as the crowdsourced list of gynaecologists — will keep giving hope to many women like Varsha during some of their darkest, loneliest times.