- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

How special magazine issues came to define Deepavali in Tamil Nadu

For a brief few weeks in the early 1950s, Tamil Nadu was gripped by what would later go on to become a tradition to celebrate Deepavali — a reading culture. An array of special articles in all genres – arts, culture, politics, etc. etc. – rolled out as special editions, Deepavali Malar, by leading Tamil magazines also, inadvertently, awakened in its readers a hunger...

For a brief few weeks in the early 1950s, Tamil Nadu was gripped by what would later go on to become a tradition to celebrate Deepavali — a reading culture.

An array of special articles in all genres – arts, culture, politics, etc. etc. – rolled out as special editions, Deepavali Malar, by leading Tamil magazines also, inadvertently, awakened in its readers a hunger for reading.

Forty-year-old Chezhiyan is one of those readers, but certainly not the first generation in his family. He imbibed the tradition from his father, who had developed the habit from his father and Chezhiyan’s grandfather. Each year Chezhiyan eagerly awaits the onset of Deepavali season. For him, more than the shimmering lights and bursting crackers, the real joy of the festival lies in Deepavali Malars. An avid reader, Chezhiyan starts making the run to nearby book stalls weeks before the festival of lights to pick up copies of Deepavali Malar by various publications.

But the past two years, passed under the clouds of the pandemic, have turned Deepavali duller for Chezihyan and hundreds of those in Tamil Nadu who wait to lay their hands on Deepavali Malars and spend hours reading them or just putting up on their walls the ‘blow-ups’ that accompany the special editions.

“Most of the publications have either stopped or reduced the number of copies of Deepavali Malar over the past two years. This year as well, the situation is no different. Usually, most publishing houses bring out their Malar at least three weeks before Deepavali. But this year, in many shops it is hard to find more than three special issue magazines from different media houses,” Chezhiyan told The Federal.

Deepavali Malars, the special edition magazines, brought out by publishing houses around the festival of lights have had a rather interesting relationship with the shaping of the economy of the state where Deepavali is not the primary festival, but seen more as a north Indian gala.

The publication of special issue magazines has at least a half-a-century-old history. Close observers say the tradition of Malar — which means flower in Tamil — gained popularity with Deepavali itself starting to find greater prominence in the list of Tamil festivals.

Traditionally, the most important festival for Tamil Nadu has been Pongal which falls in the Tamil month of Thai (January). The story of how Deepavali became popular in the state itself makes for an interesting story.

An urban phenomenon

Unlike Pongal, Deepavali is not celebrated on a pan-Tamil Nadu scale.

Cultural historian and former professor of Tamil at Manonmaniam Sundaranar University, Tirunelveli, late Tho Paramasivan believed that Deepavali has remained an urban festival and is celebrated by Hindus alone.

“The festival has become an important driver of the urban economy, influencing the sale of textiles, crackers, flour and oil. Due to the media, the festival has been perceived across India as a national festival, which is also celebrated by Tamils. Pongal, on the other hand, is still limited to a rural and traditional economy-based festival. It is a harvest festival and that is why it is celebrated by people across religions. Even in Roman Catholic Christian churches, people celebrate Pongal. But Deepavali celebrations are restricted to mostly Hindus,” he wrote in an article in Tamil.

“Crackers, considered as one of the central things about Deepavali celebrations, were not introduced to Tamil Nadu until the 15th century. Even the word Deepavali, which literally means line of earthen lamps, was known. Paramasivan argued that it was only during the Vijayanagara Empire that the festival came into prominence. That is the reason why Telugu Brahmins in Tamil Nadu celebrate this festival more religiously, he said.

“Deepavali is celebrated against the backdrop of the killing of Narakasura [and it mostly falls in the Tamil month of Aippasi — between October 15 and November 15]. On the other hand, Jain’s celebrate the same day as the death anniversary of Mahaveera, the 24th Tirthankara. Another interesting thing is that Tamil Nadu Brahmins celebrate this festival by taking an oil bath, a practice which is not seen among the Hindus in north India or Jains,” Paramasivan wrote in his article.

Economic significance

Every year, families across cities in the state start filling their wardrobes with new dresses, making sweets, bursting crackers and enjoying a newly released movie.

Talking to The Federal, writer Tamilmagan said that people in Tamil Nadu started to celebrate Deepavali mostly because it was around this time that business enterprises used to pay bonuses to their employees.

“The companies usually pay bonuses at the time of Deepavali. When people have money they naturally go shopping and a lot of business takes place. The film industry also started to exploit this aspect by releasing new films on this day,” Tamilmagan said.

Interestingly, the first Tamil talkie, Kalidas, was released during Deepavali in 1931. The tradition was followed by the actors such as Sivaji Ganesan.

As opposed to this superstar, MG Ramachandran, being a cadre of Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam then, used to release most of his films on Pongal since it is associated more with Tamils than Deepavali, which was considered a Brahminical festival.

“The bonus paid to the employees inadvertently pushed them to go shopping. That pushed the shops to advertise more. That in turn led the publishing houses to accommodate more pages. And that’s how print media started to bring out special issues which have more pages unlike the regular issues. For example, if the regular issues had some 100 pages, due to advertisements it could have some 30 additional pages. In order to balance the advertisements, the media houses brought another 20 pages with exclusive interviews, short stories, festival-related comic strips, food articles, etc. So the special issue magazines have 150 pages,” Tamilmagan explained.

Later, media houses started to bring out standalone dedicated special issue magazines in a digest format and called them Deepavali Malar. The regular issues were also published but as two or three volumes in the festival week, instead of just one regular volume.

Special issues needed special and dedicated staff.

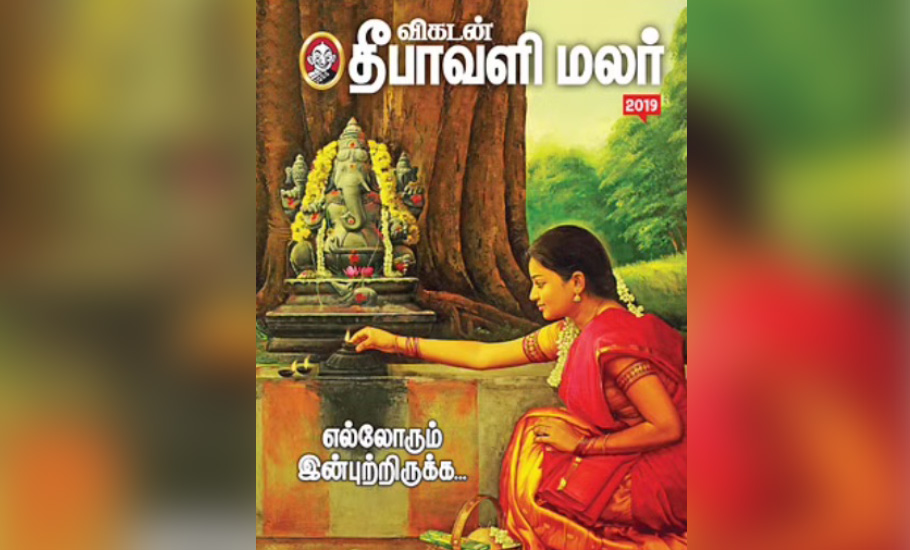

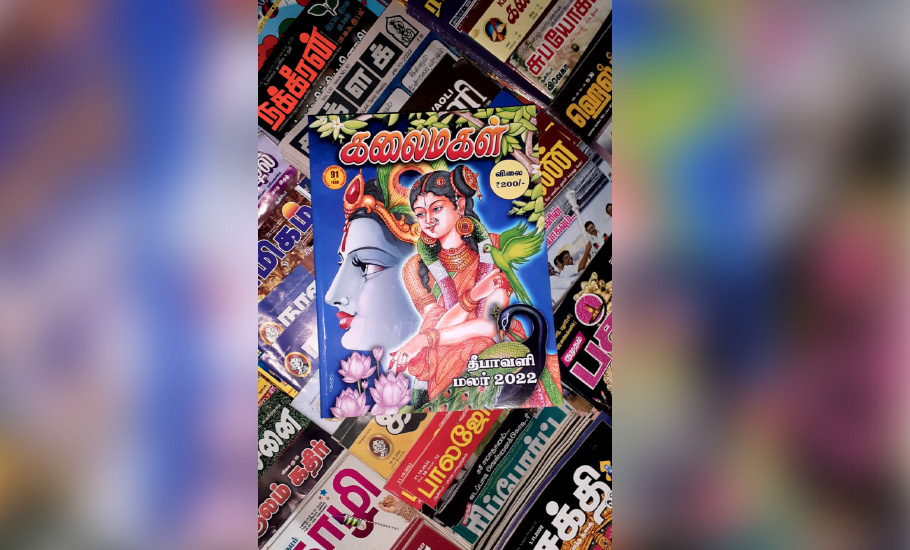

“When media houses started to bring out standalone special edition magazines, popular publications like Vikatan, Kumudam, Kalki hired dedicated teams just to bring out the special editions every year. These publishing houses have been bringing out Deepavali Malars since the 1950s,” Tamilmagan added.

Not a marketing gimmick

A senior journalist who works in one of the leading Tamil magazines and heads the team of special editions, on the condition of anonymity, said at least for some traditional media houses like Vikatan, Kalki, Kalaimagal, Amudha Surabhi, Dinamani, bringing out Deepavali Malar is not a marketing gimmick. It is, in fact, born out of a true sense of readership loyalty.

“We bring out special editions purely to promote the reading culture. In a 400-page special issue, only 40 to 50 pages carry advertisements. It’s hardly 10 per cent. The remaining pages are filled with exclusive content,” he said.

Take for instance, Vikatan, which is going to celebrate its centenary in three years. Vikatan has been bringing out Deepavali Malar since the 1950s uninterrupted except for a brief period when ‘nasty business moves’ by competitors forced the publishing house to halt the special edition.

Ban on prize schemes

“The culture of bringing out Deepavali special issues turned nasty when Thinaboomi, a Tamil daily, linked its Deepavali special issue with marketing for the sole purpose of commercialising it. In 1999, it announced that it would be publishing a ‘Deepavali Special Malar’ at a cost of Rs 100 and those who buy the issue would get an assured prize coupon inside the Malar. On producing the prize coupon, the buyer was assured of gifts and, if lucky, a bumper prize,” the journalist said.

“The prizes ranged from stoves, mixer grinders, tape recorders to movie tickets. The offer drew in hordes to shops to buy the special issue. When the time for prize distribution came, the mismanagement of crowds led to violence. Blows and fisticuffs were exchanged between readers, agents and staff at the shop that sold the magazine. A reader, who felt cheated by the publishing house, filed a case. While hearing the case, the Madras High Court banned the prize schemes under the Tamil Nadu Prize Scheme (Prohibition) Act, 1979,” said the journalist.

The court observed that the value of the prizes given along with the magazine should not exceed the cost of the magazine. Following the unfortunate set of events, most magazines stopped the practice of giving gifts to their readers.

“However, some publications even after the court order, gave SIM cards etc as gifts along with the Deepavali special issue. This resulted in people buying the special issues only for the prizes but not for the content,” the journalist said.

This competition forced some of the traditional publications to stop bringing out special publications for a few years. These publications started printing the special issues only after the court ruling created a level-playing field.

“As far as content is concerned, the Deepavali Malar has offbeat and long-format stories which cannot find a place in regular issues. Printed in art papers, the magazines have detailed interviews of celebrities, travelogues, photo stories, writings on food, short fictions, comic strips, among other interesting things. In olden days, these magazines had ‘blow-ups’ which readers could frame and hang on their walls. Those ‘blow-ups’ would mostly be that of temples and Gods. Popular artists such as Silpi used to spend days together sitting in temples to draw the ‘blow-ups’ for the magazines,” the journalist said.

Online resurgence

In the aftermath of Covid when businesses took a hit, except for two or three publications, most publishing houses did not bring out Deepavali Malars in 2020 and 2021. The rising cost of printing added to the woes of the publishers. While publishing of hardcopies stopped, media houses opted to print copies of Deepavali Malars online. To read these special issues, readers need subscriptions.

Magazines like Kalki have gone online completely. Others like Vikatan have both print and subscription-based online editions. And then there are magazines such as Amudhasurabi that have both print and online editions but their online editions are free.

While the charm of hard copies is missed by many in Tamil Nadu, many others are making the switch to digital copies. But fortunately or unfortunately, there are still hardcore readers like Chezhiyan who believe it is what you are reading that matters, not where and on what format.

“Although the readership for print magazines has been falling, it doesn’t automatically mean that the reading culture is declining. Readers are increasing and only the format of reading has changed. This is applicable to special issue magazines also,” Chezhiyan said.