- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

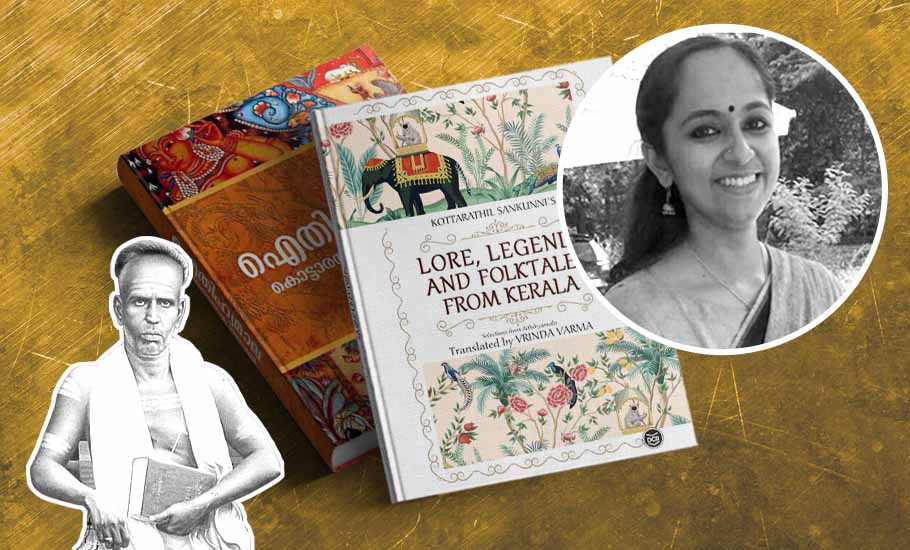

Gained in translation: Folk literature and other ‘gospel truths’ from Kerala

Kottarathil Sankunni’s Aithihyamaala (Garland of Legend), a popular lore and legends from Kerala, has now been translated into English by Vrinda Varma.

Kottarathil Sankunni’s Aithihyamaala (Garland of Legend) is one of the most popular one-of-its-kind collections of lore and legends from Kerala. It is a classic and a true chronicle of Kerala history, albeit with kings, warriors, elephants, deities, sirens, sorcerers and wizards. Stories like the Kadamattathu Kathanaaar, an exorcist of yore, who has inspired a television...

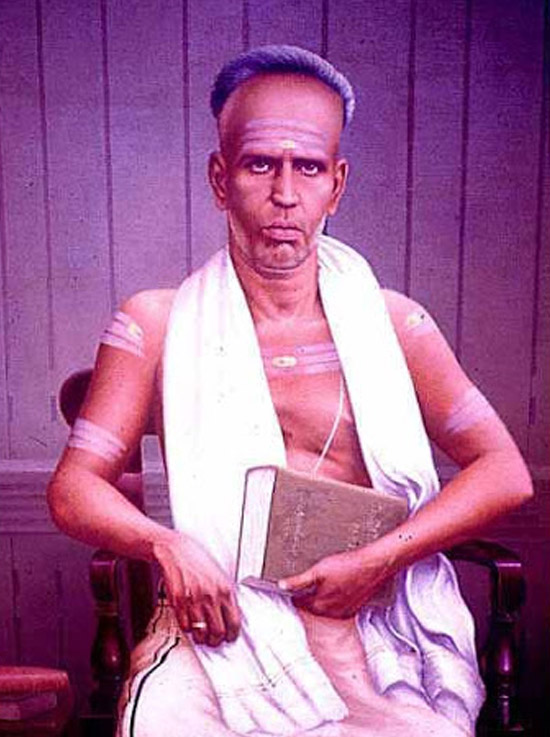

Kottarathil Sankunni’s Aithihyamaala (Garland of Legend) is one of the most popular one-of-its-kind collections of lore and legends from Kerala. It is a classic and a true chronicle of Kerala history, albeit with kings, warriors, elephants, deities, sirens, sorcerers and wizards.

Stories like the Kadamattathu Kathanaaar, an exorcist of yore, who has inspired a television series; Kaayamkulam Kochunni, the highway bandit, which was released in its umpteenth movie version as late as 2018; stories of the Pambarambathu Kodanbharaniyile Uppumanga and Parayi Petta Panthirikulam have always been a part of every Malayali’s childhood memories.

Dr Vrinda Varma, assistant professor of English at the Kerala Varma College, Thrissur, took up the highly-ambitious project of translating 75 of the 128 stories into English.

The magnum opus—Lore, Legends and Folktales from Kerala published by DC Books—hit the bookstands last Christmas. Written for the global contemporary reader, this is a must-have in every Malayali home.

Here are excerpts from an interview with Varma:

You translated Malayalam literature’s most popular collection of 75 folklores from near-archaic prose into contemporary English in three months. How?

It was a daunting task. I’ve grown up with the Aithihyamala stories. They were grandmother’s tales for me, albeit in its brief, oral form. So the sense of familiarity did help.

Kottarathil Sankunni’s prose is not in the least contemporary, but almost archaic. But as a college teacher who has done plenty of research, I resorted to the Puranic Encyclopeadia in Malayalam by Vettam Mani and Dr Nellickal Muraleedharan’s Kerala Jathi Vivaranam (2011).

Again, the internet doesn’t give you all the accurate answers. I got a lot of help from family and friends who were experts and well-versed in terminologies and age-old traditions.

Give us a few examples.

For instance, many of the stories in the Aithihyamala are based on temples, its architecture and rituals. Whenever I came across a word in Malayalam that had a strong vernacular relevance but would be incomprehensible to the contemporary global reader, I’d mark it immediately and describe it in detail as a foot-note.

For example, the last story Mandakaattammanum Kodayum is a highly descriptive piece that has words like koda, kodiyettu, valiya padukka and so on. A ‘padukka mandapam’ is mentioned. This is a seating for the royalty, but not a dais by itself. Its colour is also a rare shade of gold. Such translations are laborious and time-consuming.

But not all translations are technical. A lot of the stories are written on elephants. For a Malayali, the elephant is an emotion. It’s everywhere. It’s a symbol of aristocracy and power for the upper-class owner, but also a friend and brother to its mahout, a source of pride for the whole village. The emotions that an oral folklore inspires should not be lost in translation.

The Yakshi is another example. A yakshi is neither a celestial being nor a sorceress. Is it simply the ghost of a woman who died unnaturally? The Malayali wouldn’t agree.

So is the Velichappadu. There is an exact translation in English—the ‘oracle’. But Greek literature uses the same word in all its adaptations. The Velichappadu of Kerala is a far cry from its Greek counterpart. The global reader would only be confused and nonetheless enlightened. In both cases, therefore, I retained the Malayalam words.

As a feminist academic reader, your personal take on these stories?

Sankunni was partial to his characters. His prejudices are evident when he describes the royalty, the Nampoothiri class and even the women. His writings are peppered with jargon that show extra-reverence to these kings and rulers.

In the story Kayamkulam Kochunni, the Moossa Namboothiri asks Kochunni – ‘Promise me that you shall not hurt a Brahmin henceforth.” In Shakthan Thampuran, there is a massacre of 500 people to smoke out one culprit. Sankunni writes of it very subjectively without condoning it. Today, no chronicler would get away with such liberties.

His women are addressed as Antharjanam, Namboothiri sthree, Shudra sthree and so on. He doesn’t name his women characters much. But I didn’t give names either. That would be akin to erasing their identity. As a feminist, I may not agree with it but as a translator, I did tone it down a little for the contemporary reader. If prejudices abounded in the text, it is a telling of those times.

What is the reason behind the Aithihyamala’s popularity since 1904?

The fact that Sankunni was of the educated elite may have given him the privilege and the access to chronicling these oral legends into its written form. Plus, he was commissioned to write them by Varghese Mappillai, Kerala’s best known publisher at the time.

The stories are of demi-gods and demi-goddesses, celestial beings, temple rituals, royal lives and decrees—all elements of the upper-class which are especially popular when glorified. Today, it is one’s go-to book, as a starting point for all the stories and legends from Kerala.

I think the initial translation by Sankunni, from the oral to the literary, and his efforts at compiling all them under one cover is the most remarkable feature of this work, and the reason why people still read it today.

How relevant is this English translation in today’s world?

Literature has its own relevance—it’s the gospel truth. Moreover, a lot of interest has been rekindled in folktales. Be it fiction or fantasy, lore and legends have an enthralling effect. A contemporary reader may find it preposterous, for instance, that a Yakshi bride conceived and gave birth. But I had to make sure that I did not trivialise these stories in translation.

At the same time, I have stripped it off its archaic jargon. For instance, the hands of the King will be written as ‘hands’, not ‘divine hands’. Like I said before, the extra-reverence that Sankunni gave to royalty is irrelevant for the contemporary reader. I have retained the tone only where it was absolutely necessary.

This book is for the contemporary global Malayali reader above 20 years. I have tried my best to make the text palatable. A cultural aficionado can hope to be entertained while a more serious academic can take it as a starting point for more serious research.

How easy was the process?

I had a tight deadline. Around 900 pages in three months. I started mid-week of August 2020 and submitted my final draft on October 23. I had taken a sabbatical from teaching for a while and so could focus entirely on this assignment.

I would read two to three stories from the Aithihyamaala every night before going to sleep. Next morning, I would start translating the same. Each story had to be simple and with absolute clarity. I kept my translations paragraph to paragraph but not word to word.

A lot of time went into getting the right descriptions in English. I had the advantage of knowing some of these stories as bedtime tales but during translation, I realised it was not the way I remembered them. The novelty helped.

What is the role of the translator?

I think translators are grossly undermined. Authoring a work and translating a work require two different skill-sets. If I had stayed true to the text, a contemporary reader might find the Aithihyamaala dull. If I had stayed true to the reader, then the story might lose its soul. I had to strike a balance.

Also, translations are assignments. They are pre-ordained tasks as opposed to bursts of creativity. While I translate, it’s as if someone is looking over my shoulder.