- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

A faltering Ujjawala scheme pushes rural women back into smoky kitchens

Squatting before an earthen hearth in her cramped kitchen, Radhika Gowala huffs and puffs as she tries to light a fire with woods she collected from a nearby forest. Incessant rains in the area left the tree branches she picked up from the forest moistened. Wafting toxic smoke all over Radhika’s frail and ageing frame triggering a bout of cough, eye itching and running nose, the wood...

Squatting before an earthen hearth in her cramped kitchen, Radhika Gowala huffs and puffs as she tries to light a fire with woods she collected from a nearby forest. Incessant rains in the area left the tree branches she picked up from the forest moistened. Wafting toxic smoke all over Radhika’s frail and ageing frame triggering a bout of cough, eye itching and running nose, the wood just refused to catch fire.

The sorry state 56-year-old Radhika, resident of a forest village in West Bengal’s Alipurduar district, found herself in is a sad saga of how another of a much-hyped scheme of the Narendra Modi government has gone up in smoke.

Radhika from Garo Busti, a forest village on the outskirts of Buxa Tiger Reserve, was among thousands of beneficiaries provided with subsidised gas connections and cylinders under the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY), a flagship scheme of the Modi government launched on May 1, 2016.

The scheme meant for families living below the poverty line was “aimed at replacing the unclean cooking fuels used in the most underprivileged households with clean and more efficient LPG (Liquefied Petroleum Gas),” according to a PIB article circulated in August 2106 under the title Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana: A Giant Step Towards Better Life For All.

The article written by then deputy director (media and communication), PIB, Kolkata Ajay Mhamia, went on to claim that the “main mantra of this scheme is Swachh Indhan, Behtar Jeevan – Mahilaon ko mila samman” and that it was in line with the Prime Minister’s dream of creating smokeless villages across the country.

True to the initial promise, almost all the 30,000 families residing in 65 forest villages and another about 1.6 lakh families living in 67 tea estates on the fringes of forests in the district benefited from the scheme, Lal Singh Bhujel, convener of the Uttarbanga Van Jan Shramajeevi Manch told The Federal.

Radhika opted for a free gas connection and subsidised LPG five years ago, in 2017, in a similar rainy season.

“Our joy knew no bounds when we got the gas connection. Suddenly, our life had changed for the better. We did not have to venture into the forest inhabited by wild animals to collect firewood. Cooking became so easy and hassle-free. We could start a fire with a flick, and there was no smoke and soot,” said 42-year-old Sumitra Gowala, another resident of Garo Busti.

“Cooking on chullahs is an arduous task besides being risky and unhealthy,” Radhika chipped into the conversation, supporting the views of her neighbour. She could barely complete a sentence without breaking into bouts of coughing and frantic rubbing of itchy eyes with the back of the hand as she tried making tea for her guests.

“It would have hardly taken her five minutes to make the tea on the gas stove and that too without adversely impacting her health,” Sumitra added.

The Ujjwala scheme brought immense benefits as it helped people such as Radhika and Sumitra from risking their lives encountering wild animals in a bid to collect firewood. They were also saved from breathing in the smoky fumes equivalent to smoking 400 cigarettes per hour (as per a claim made by the government). Since cooking on LPG became faster it also meant women in the house had to spend less time in the kitchen.

“It also helped in the conservation of forests and biodiversity,” Bhujel said. “A typical family of six to seven members like that of Radhika and Sumitra, in these forest villages, need around 70-75 kilos of firewood a month,” he added.

“We wholeheartedly supported the scheme because it was a great help to the village women as well as to the environment,” said Bhujel, whose organisation works for the protection of biodiversity and rights of forest dwellers.

But after over nine crore families across India availed the benefits of the world’s largest energy programme to promote cleaner cooking fuel, the gains of the scheme are frittering away. Due to surging prices and reduction of subsidies, most families like that of Sumitra and Radhika are back to using firewood to cook three square meals a day.

“I last refilled my cylinder after months in 2021 during the monsoon season when the firewood became wet and wouldn’t burn,” Radhika said.

A 14.2-kg LPG cylinder cost her around Rs 860. Of this, cash back of around Rs 350 was credited into her account. The stove and cylinder are now carefully kept in one corner of Radhika’s kitchen and she is back to struggling before the chullah.

Her husband is an agricultural labourer, who earns between Rs 5,000 and Rs 7,000 in a month.

“Earlier, he could supplement his income by working in MGNREGA schemes. But work under the scheme has now stopped, limiting our family earnings,” she added.

The Centre has not released MGNREGA funds for West Bengal since December 2021, impacting rural jobs and family incomes.

“We now again go to the forest to collect minor timber, tinder and twigs to light our hearth. Nature has given us enough to take care of our needs, we don’t want the government’s false promises,” Sumitra said.

A cylinder in Alipurduar now costs Rs 1,129, which is beyond the means of most people living in forest villages and tea gardens, said Gopal Pradhan, the president of the Dooars Cha Bagan Workers’ Union.

He said ever since the government slashed subsidies for Ujjwala beneficiaries, no one is refilling the cylinders. “You will find their gas stoves rusting in the cowshed,” Pradhan added.

Since June 2020, Ujjwala beneficiaries get a subsidy of only Rs 200 per cylinder for 12 refills in a year.

The impact of the subsidy cut has pushed the poor women back to chullhas across the country. The increasing cost of a refill and thereby affordability is a huge deterrent.

“When the scheme was launched, the cost of a cylinder was Rs 419.15 and now it is Rs 1,062. Moreover, there is no gas agency near most of the villages and tea estates. So villagers have to pay another Rs 150-200 for transportation of empty cylinders to the agency and filled ones back home. Increasing cost of refill has made this scheme useless,” Pradhan lamented.

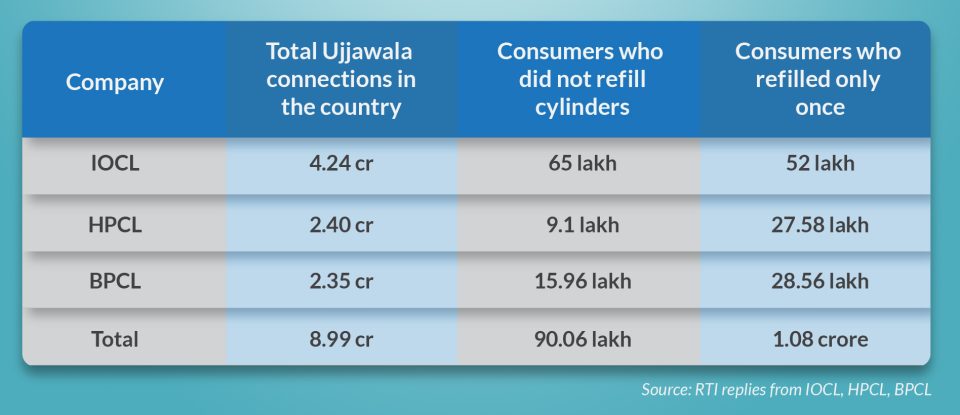

Between April 2020 and March 2022, 90 lakh beneficiaries of the Ujjwala scheme in the country did not refill their cylinders, three oil marketing companies said in a recent reply to a Right to Information (RTI) application filed by activist Chandrashekhar Gaur.

Indian Oil Corporation Limited (IOCL), Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Limited (HPCL) and Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited (BPCL) told Gaur that another over 1 crore beneficiaries refilled their cylinders only once.

The government has so far not come up with any policy intervention to arrest the trend of women going back to chullahs unable to afford refilling the cylinders that the government gave them tom-tomming it as the biggest step towards improving the health of rural women and building a greener future.