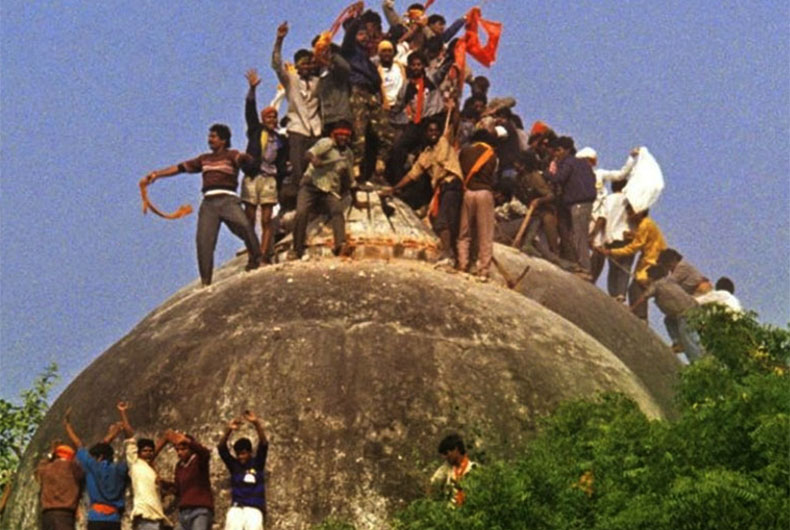

Impact of Babri Masjid demolition: Unveiling the hatred 30 years later

Over the years, one would have thought the Ayodhya issue would have paled into insignificance. But, on the 30th year, it is clear issues flagged during the demolition pertaining to cultural nationalism has gained traction, religion the main basis of social identity and vengeance a justified sentiment

“The face of Indian polity has undergone a dramatic change in the last decade, and a new political and social order appears to be around the corner. The model evolved in India after Independence, during Jawaharlal Nehru’s tenure, is under threat and close to being dismantled.”

I began writing my first book, The Demolition: India At the Crossroads, in January 1993 with these lines. Several friends initially accused me of being “obsessed” with Ayodhya and argued that “I was wrong in believing that the RSS clan would come to the centrestage in India. And, when the Babri Masjid was demolished, it was a sad hour of personal vindication for me.”

At the book’s launch, a year later, KN Govindacharya, then an important Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leader, asserted that the Babri Masjid’s demolition was comparable to the fall of the Bastille, in terms of what it represented, as well as the impact its erasure would have. Other panellists, including the deceased journalist and then Congress leader Nikhil Chakravarty and P Rangarajan Kumaramangalam, respectively, along with historian KN Panikkar and political scientist Kamal M Chenoy, disagreed equally passionately.

Govindacharya’s two contentions appeared untenable – certainly, the Babri Masjid did not symbolise absolute power of any medieval emperor, much less Babur at whose command the mosque was purportedly built. The structure in Ayodhya also did not represent ceaseless tyranny.

The impact that Govindacharya claimed it would have, appeared exaggerated for the BJP was defeated barely weeks after in the first set of post-demolition polls in Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Himachal Pradesh and barely cobbled together a majority in Rajasthan – these states were ruled by the BJP but the governments were dismissed after the events of December 6 1992.

Also read: Project to ‘rewrite’ Indian history a milestone in 4 decades of RSS efforts

Some years after the demolition, I too veered around to the view that my response in 1992-93 was an instance of overreaction; Atal Bihari Vajpayee had become Prime Minister a few months after the fifth anniversary of the demolition at the head of an ideologically awkward coalition, where partners had not joined the political jumble for fulfilling stated programmatic objectives, but to acquire and remain in power. What many secularists asserted paradoxically in the immediate aftermath of the demolition, that the tragedy would in the long run “prove to be good for India,” appeared to have been an accurate reading.

This lot had argued that the sixteenth century mosque was a ‘small’ price to pay for ensuring that the BJP and its Sangh Parivar affiliates “lost their hate symbol” forever. Arousing communal passions, hatred for Muslims and spreading incessant otherisation on every issue would prove to be difficult, it was believed, because there no object would remain that could exemplify humiliation of Hindus in the past, for which vengeance had to be secured.

The misleading continuity

This assessment appeared correct for the BJP eschewed not just the Ram temple imbroglio, but also chose silence on two other contentious issues that marked its ‘difference’ from other parties: abrogating Article 370 of the Constitution and enacting a Uniform Civil Code. Vajpayee also pursued peace with Pakistan and travelled to Lahore on a bus that kick- started another form of public transport between the two countries.

Incidents like the killing of the Australian missionary Graham Staines, the 1998 attacks on Christian tribals in south-eastern Gujarat and finally the horror of the riots in the state in 2002, caused concern, consternation and condemnation from even several alliance partners. As a result, it appeared violent incidents like these were aberrations and not the result of deeply nurtured prejudice against the religious minorities, especially Muslims and Christians.

Communal riots and orchestrated attacks for electoral and political purposes were part of India’s post-colonial history. Despite episodic violent attacks like those aforementioned, the moral compass of Indian polity remained more or less in the pre-Babri demolition position.

Also read: Rewriting history to ‘cleanse’ India’s list of national icons

The BJP surprisingly lost the 2004 elections and a ‘non-politico’ in the traditional sense, became prime minister. Vajpayee candidly confessed that his government was voted out because of the Gujarat riots. When the original polariser, Lal Krishna Advani discovered virtues in Mohammed Ali Jinnah, that too in Pakistan, it appeared that India had exorcised the ghost of Babri Masjid and it appeared that the makeshift temple shall remain in perpetuity; no grand temple would ever be constructed.

Anniversaries of the demolition became routine – celebrated as a day of ‘valour’ (Shaurya Divas) by Hindutva groups and as a day of sorrow and betrayal by secular groups and Muslim organisations. Yet, the temple per se did not evoke enthusiasm and it looked certain that none of the affiliates of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh would succeed in mustering the kind of crowd that assembled in Ayodhya for confrontational programmes in 1989, 1990, 1991 and 1992.

Watershed anniversaries too – fifth, tenth, etc., – failed to become major flashpoints and merely served as markers of time for commentators to take stock and for civil society to debate and hold discussions. The 10th anniversary in 2002 added to the din of the epochal Gujarat Assembly polls but by the time of the 15th anniversary in 2007, the Ram temple issue had become inconsequential.

In another five years, the BJP’s period in wilderness seemed to be coming to an end with the UPA government crippled for a variety of reasons but aptly explained by a two word phrase: policy paralysis. But more importantly, 2012 was ushered out with Narendra Modi leading his party to victory in Gujarat for the third time since his assumption to office in 2001 and immediately launching a dash to become the prime minister.

Modi’s ‘victimhood’ construct

Although the 2014 Lok Sabha election was contested with ‘development’ as a keyword, there was little doubt that retribution was the foundational sentiment on which Modi constructed his campaign. A decade of victimhood, in the course of which he constructed a troika of adversaries – enemies across the border, Indian Muslims and their supporters, (which included dynastic parties) besides the combination of intelligentsia, civil society (NGOs) and the Delhi-based English media with all of them backed by the so-called Lutyens elite, was beginning to resonate with people.

People liked to lay blame on the doorstep of someone identifiable for their woes and Modi gave them courage to do so. It was clear that Modi had not left his Hindutva mornings behind. But, middle-India required the fig leaf of ‘vikas’ – majoritarianism had not yet become politically correct.

Also read: Despite what BJP says, monoliths are a myth in Indian politics

The 25th anniversary of the demolition was observed when the Modi bandwagon, for the first time, appeared to be facing difficulties in maintaining its political dominance in Gujarat. Eventually, the BJP salvaged victory after Mani Shankar Aiyer handed Modi a plateful of slander that could be heaped on the Congress party by hosting a dinner attended by dignitaries, including former Pakistani diplomat Khurshid Mahmud Kasuri, former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh besides former Vice-President Hamid Ansari. It was the ‘perfect’ cast – a Pakistani, someone high up in the Congress and a Muslim not a favourite by yards. This was followed by Aiyar calling Modi a “lowly” person.

The result was for all to see. More than a decade of Modi’s responses to accusations against him were resurrected in people’s minds after he recast the old formula of inimical forces working to derail his efforts to revive India’s past glory. The BJP eventually snatched victory with a slender majority that could have further thinned, even may have been denied, had not Aiyer asked friends and colleagues to come and dine with him.

Subsequent events demonstrated that in the decade since the defeat of the Vajpayee-led BJP, the Ayodhya issue by itself may have paled into relative insignificance, but issues flagged in the course of the agitation, especially ones pertaining to cultural nationalism that people once had no understanding off, had gained traction with people.

The 30th anniversary of the demolition is being observed days prior to yet another verdict from Gujarat. But regardless of the outcome, the socio-political drift shall remain the same, as demonstrated during the campaign when no party raked issues that might offend the Hindu voters.

Merging of myth and history

Today in India, mythology and history are spoken in one breath, not just by the establishment but also by large sections of people. The Ram temple in Ayodhya will not act as a full stop that even the Supreme Court believed it would when the five judges awarded the disputed land to a Trust handpicked by the Centre.

A long list is in existence and it is just a matter of time before full-blown agitations are mounted for the demolition of Gyanvapi Masjid in Varanasi and Shahi Idgah in Mathura and for these sites to be handed over to Hindu parties. Expressing Islamophobia in public is no longer considered ‘improper’ in New India.

Several Muslims think twice before revealing their identity. Already, many have been officially notified in several cities, towns and villages that they must go ‘invisible’ – not offer namaz in public, not wear hijab in educational institutions, eat no home-cooked non-vegetarian food while travelling on public transport, and so on. In India today, there is greater sense that this is “our country” and “they” must live on “our terms”.

None of this has any co-relation with the Babri Masjid or the Ram Janmabhoomi agitation. But the mosque-temple dispute is at the root of each issue that makes religion the main basis of social identity and vengeance a justified sentiment. In many ways it appears that the demolition of the Babri Masjid provided courage to unveil the hatred cloistered in hearts of a significant number of Hindus for Muslims and Christians, the two main non-Indic religions.

The list of what is now possible is much longer. The catalogue of what is likely to happen can fill reams. For the moment, my last confession today should suffice: Govindacharya was prophetic three decades ago when he said the Babri Masjid’s demolition shall have unfathomable impact on the country’s governance and polity like the way the fall of the Bastille did. I, however, continue disagreeing with the formulation that the Babri Masjid mirrored the fortress, stormed in July 1789.

(Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay is a NCR-based author and journalist. His latest book is The Demolition and the Verdict: Ayodhya and the Project to Reconfigure India. He has also written The RSS: Icons of the Indian Right and Narendra Modi: The Man, The Times. He tweets at @NilanjanUdwin)

(The Federal seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. The information, ideas or opinions in the articles are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Federal)