In poll bound Maharashtra, onion farmers, traders unhappy with govt

On the morning of October 14, about 200 truckloads of onions arrive at Nashik’s Lasalgaon mandi, Asia’s biggest wholesale onion market, in Northern Maharashtra. The auctions are to begin at 10.30am. Farmers who’ve travelled from a distance ranging from 2 to 25kms, wait for traders to take stock of the crop at their disposal.

Soon after, they pour the onions on ground for a group of merchants to sample. The auction price at the first truck determines the average price for the rest of the trucks. However, the price slightly varies (plus or minus 10%) depending on the crop quality. While the first truckload gets auctioned at ₹2800 per quintal, farmers quickly move towards their respective trucks.

Gokul Mallari Darade, a 32-year-old farmer from Jaulke in Nashik sold 150 quintals of onion at rupees 2,785 per quintal. But Darade wasn’t happy. After the government put a ban on onion exports with immediate effect on September 29, the price per quintal dropped by a third since then. It dropped from ₹4,000 per quintal to ₹2,800 in two weeks.

Lasalgaon mandi sets the price trend for the rest of the country. Any fluctuation in this market price reflects in the onion price in other parts of India.

Darade, who cultivated onions in 2 acres of land producing 300 quintals was hoping to sell them at an even higher price. He waited since march to sell the crop when the prices shoot up. He missed an opportunity in September. He did not expect the government to control the rising prices which had double since August.

Firstly, previous year’s drought affected his earnings badly. As against cultivating onions in 10 acres in 2017-18, he had cropped only in 2 acres in 2018-19. And secondly, even if the output was less, the rains that followed this year destroyed half the harvested crop. So, his chances of earning more had dropped.

After deducting the production cost of ₹1.9 lakh, Darade made a profit of ₹2.27 lakh after selling his 150 quintals at ₹2,785 per quintal. Still he wasn’t happy. His anger stemmed from the fact that he could not recover a loss of about ₹4 lakh that he incurred the previous year. Darade had sold his crop between ₹200-₹300 per quintal last year.

His average production cost is about ₹80,000 per acre and the average yield is about 150 quintals per acre.

“The government should not let us suffer like this. If they want to control prices when it shoots up, they should also protect us when the prices drop below the production cost,” says Darade.

He suggests the government to give them minimum support price and sell them through ration either at subsided cost or at profit to the consumers.

Another irate farmer Dattu Vikas Sarode from Unnani village in Sinnar Taluk, Nashik, had a similar cry. He blamed the government for capping the earning opportunity of farmers. Sarode incurred a loss of ₹90,000 on his 2 acres during previous year while earned a profit of ₹1,90,000 this year.

With elections around, Sarode is vocal: “Is baar ham sarkar ko giraayenge [We will bring down the (ruling) government this time],” he says. Sarode made a desperate sale as he was not willing to wait any further. He was sure the prices wouldn’t go up as the new stock will begin to arrive within in a month.

It appears that the farmers are unhappy even though the onion prices had rallied up for a short time. It is like a game of lottery, explains a farmer.

Farmers stock the goods for months to play with the demand and supply in the market even as they speculate the price of onions. But with the risk they take, their earnings are not predictable.

They resort to this behaviour every year with a hope to make big profits.

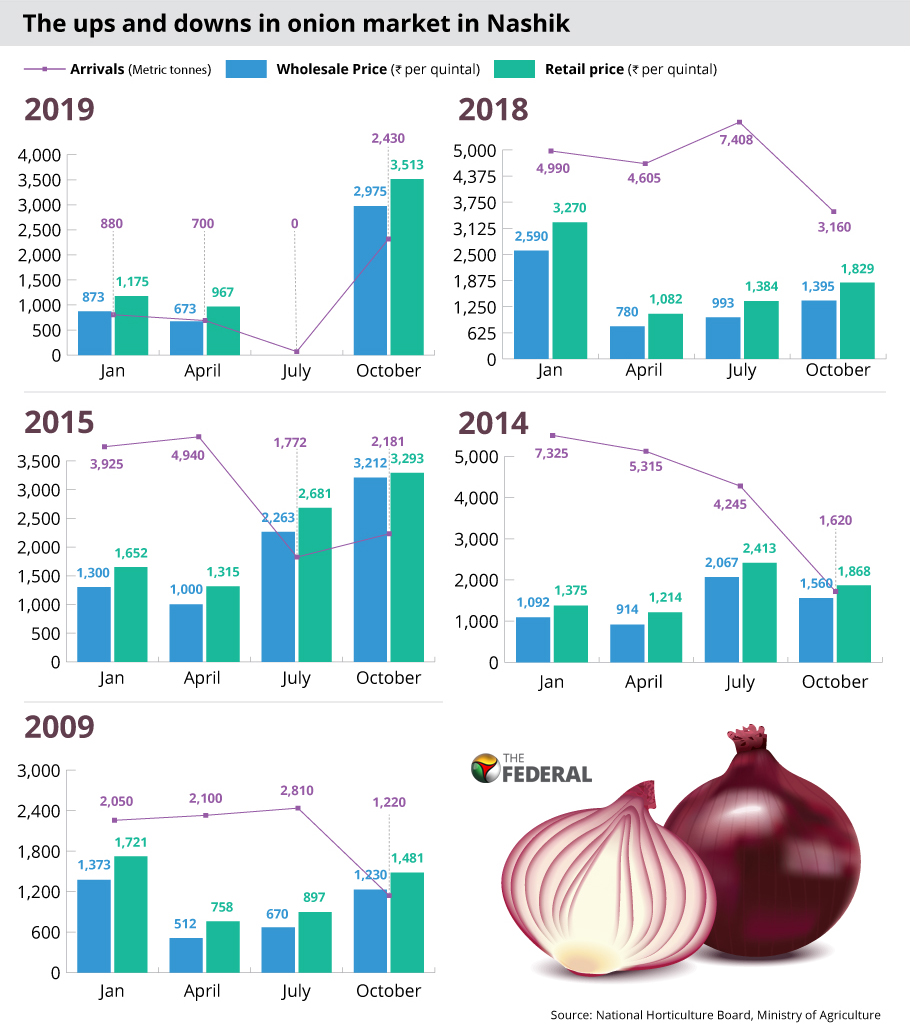

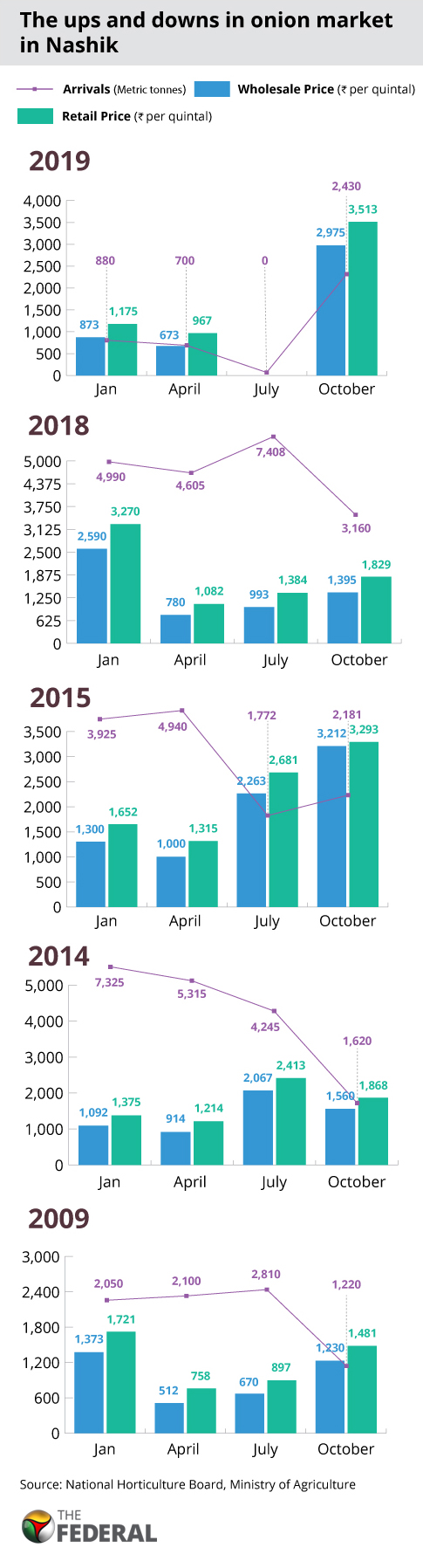

The arrivals and wholesale/retail price chart below explain the phenomenon.

Even though prices went up this year, farmers did not have enough onions to sell. At Lasalgaon, a farmer says the 200-trucks which disappeared in two hours in time, was just a tenth of what the market should have witnessed during this festival period.

When the produce was good last year, everybody lost out as the prices had crashed. And this year, the government killed the momentum by banning exports.

Merchants, too, unhappy with govt intervention

It’s even more worrying for the merchants. Praveen Kadam, a member of Lasalgaon Merchants’ Association, who’s been trading onions for 20 years says, this government, which keeps saying that Congress looted us for 70 years, was now trying to loot from them in 7 years.

The government which enforces export ban instantly, doesn’t even bother to give time to traders and exporters, he says.

Kadam, who trades 2,000 quintals of onion claims he would incur a loss of ₹26 lakh this year.

“My stocks that were to be sent to Bangladesh, some of which were in transit and some in ports in Mumbai and Gujarat were stuck. If the government bans exports overnight, how can we get them back after investing huge money,” Kadam questions.

He says, it cost him ₹50 per kg after all expenses, and it’s a hardship if he has to sell it Rs 30 a kg in the domestic market. “Who’d pay for the loss?” he asks.

As a merchant, storage is another concern for him.“If the stock lies with individual farmers, they can store in their house/farms. But we buy in bulk and cannot store it for more than 15 days. It adds to the cost besides resulting in crop damages due to long storage,” Kadam adds.

Also read | Govt bans onion export, imposes stock limit on traders to check price rise

The government takes 10 to 12 days to give export clearance during which time exporters like Kadam pack and clean the produce to match the international quality standards. So, he wants the government to give time before enforcing the ban and not do it overnight.

India produces 23 million tonnes of onion in 1.29 million hectares across the country. Of this about, 10% get exported to neighbouring countries.

The country exported 2.18 million metric tonnes of onions worth of ₹3467.06 crore during 2018-19. Maharashtra alone contribute to about 25-30% of the overall production.

The traders worry that farmers will increase their onion cultivation next year again with a hope to get good prices. They fear, this could inturn lead to a price crash again.

Onions rot in govt warehouse

The state governments like Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, New Delhi, and Assam procure onions and gives it at subsidies rate to people. They are done through National Agricultural Co-operative Marketing Federation of India Ltd (NAFED).

When this reporter visited the government warehouse in Lasalgaon where about 26,500 tonnes of onion were stored, they were rotting with no proper storage facility. Foul smell emerged as one entered the premises. Workers were segregating the good ones from the bad as they had to send it others state governments.

Sushil Kumar, the branch manager at NAFED, when questioned, said the stocks were destroyed due to heavy rains and they could not avoid it. While he officially declined to comment on the extent of crop loss, one of the workers at the unit said, 50% of the stocks were damaged.

Whether farmers benefit or not, for the government price rise will affect its large vote bank and hence it resorts to control inflation.

It is a poll issue. In 1980s, Indira Gandhi swept to power by taking soaring onion prices as a reason to bring down the previous government. Similarly, in 1998, the BJP government in Delhi was voted out of power owing to high onion prices.

The questions remain as to how far will this issue affect the upcoming polls even as the farming community resents.