- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How Girish Karnad’s Tughlaq walks among us even today

Muhammad: But how can I explain tomorrow to those who haven’t even opened their eyes to the light of today.- (Scene VI, capturing Muhammad’s reaction in Tughlaq, a play by Girish Karnad) While Muhammad-bin Tughlaq lived and ruled in the fourteenth century, his life throws light on the many complexities of the socio-political developments of modern-day India. Muhammad-bin...

Muhammad: But how can I explain tomorrow to those who haven’t even opened their eyes to the light of today.

- (Scene VI, capturing Muhammad’s reaction in Tughlaq, a play by Girish Karnad)

While Muhammad-bin Tughlaq lived and ruled in the fourteenth century, his life throws light on the many complexities of the socio-political developments of modern-day India.

Muhammad-bin Tughlaq, the eighteenth sultan of Delhi, ruled the region from 1325 to 1351, but a play based on his life’s eccentricities, choices and peculiarities continues to hold sway over theatre lovers simply by being able to find resonance with the audience over six decades.

Tughlaq, Girish Karnad’s iconic play, that has seen hundreds of productions over the past six decades and multiple translations will complete 60 years in December. When it was published, this 13-scene play, about the turbulent rule of Tughlaq of the 14th century, was interpreted as an allegory on the Nehruvian era. Karnad freely blended fact with fiction to give the story a contemporary relevance. The play, then, represented the hopes and disappointments in the political life of the Nehruvian era in Indian politics.

It voiced the disillusionment of the people of Karnad’s generation with Nehru’s idealism.

What has perhaps allowed the play to hold people’s attention has been its power to adapt itself to contemporary socio-political developments and act as a commentary on the times in which it has been staged.

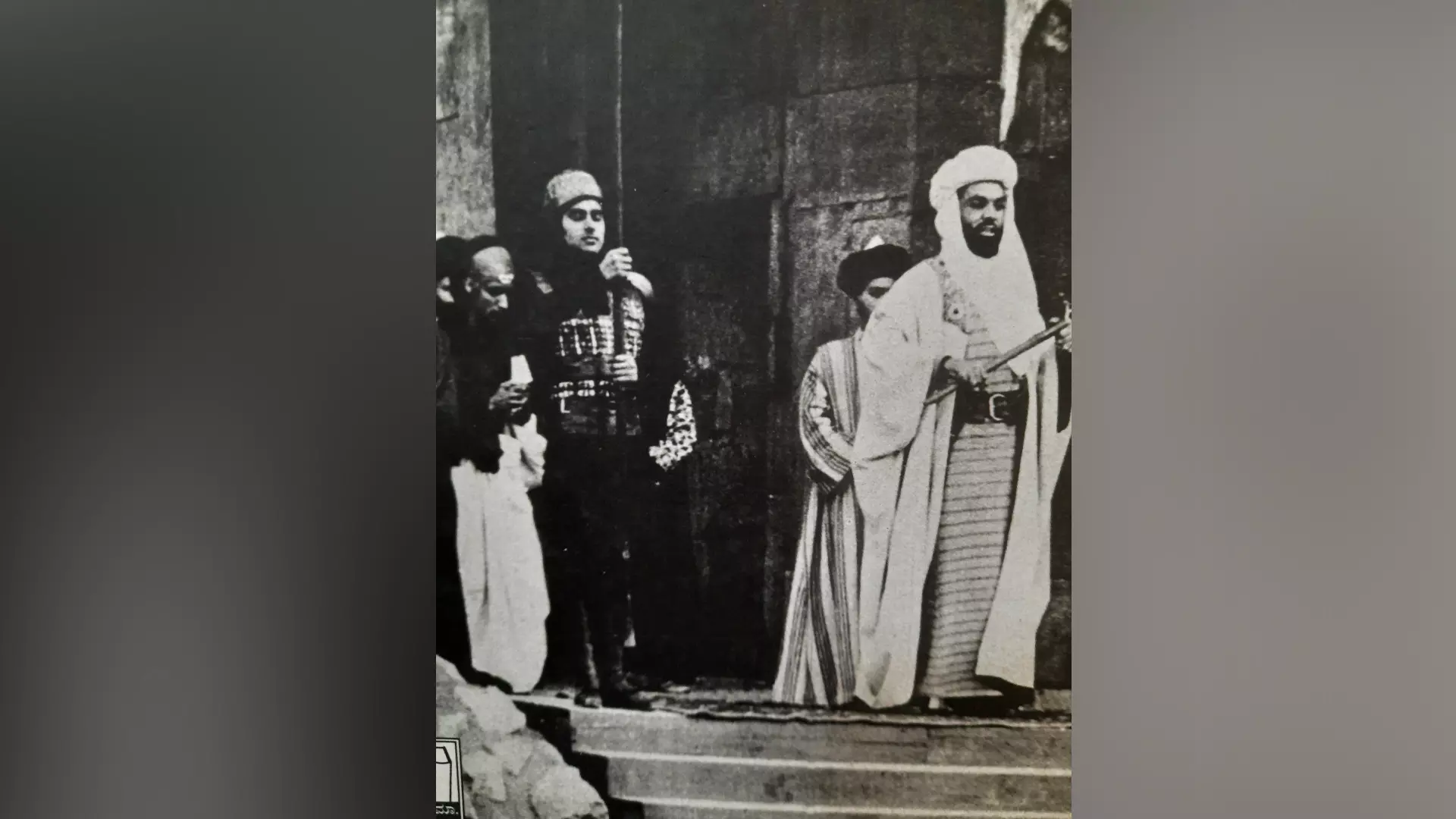

A still from Tughlaq staged by Samudaya in Bengaluru.

It is significant that Tughlaq has seen a number of new interpretations in keeping with the changing times. In fact, Karnad himself made minor changes and corrections after the sixteenth edition was published by Manohara Grantha Mala. The 90-year-old publishing house brought out the first edition of Tughlaq in 1964. Manohara Grantha Mala — the foremost publication in Kannada has the reputation of publishing all works of Karnad in Kannada. It is important to note that the Kannada edition of Tughlaq has been reprinted 30 times by Grantha Mala in the past six decades.

Samudaya, the first radical theatre movement in Karnataka, that fought the Emergency, imposed by then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in 1975, has been staging Tughlaq for the past 10 years and will cross its 100th show mark shortly. The play is directed by Samkutty Pattomkary of Kerala Sangeetha Nataka Akademi.

Karnad’s take on the play

In 2014, during the Bengaluru Literary Festival (BLF), Karnad said, “It took me two years to complete Tughlaq. It is for others to decide about the play’s relevance today. I lose interest in what I write. Once I complete it, I think only about the next thing I plan to write. A play faces its real test each time it is produced. I am happy that the play has been experimented by various theatre directors in the past five decades.”

Fifty-two years ago, in an interview Karnad recalled that Tughlaq struck him as “the most idealistic, the most intelligent king ever to come to the throne of Delhi”, including the Mughals, who nevertheless ended as “one of the greatest failures”, because of contradictions within his personality and the self-defeating nature of his politics. The 13 scenes of the play, though closely related to the first two decades of Indian independence, also addresses the emerging ambivalences of power relations in the public and political spheres that were based for the first time in India on the principles of mass representation and enfranchisement. The binaries of the ruler and ruled and the mysterious inner chamber of power politics. The open and the public areas of those affected by it, forms the bedrock of the play.

Politically, the play shows Tughlaq’s many decisions leading to chaos, not being just and liberal towards the majority Hindu population, that he being a Muslim ruler, chose to persecute. Simultaneously, the play also uncovers Tughlaq’s sadistic, manipulative impulses, which undercut his image as an exemplary ruler. But the play’s paradigmatic qualities as a historical fiction and its cultural vitality derive principally from the multifold engagement with history, that lies behind the words and function differentially in the process of ‘reading and ‘watching’ the play.

Tughlaq's social alienation

In her essay ‘Social Alienation in Karnad’s Tughlaq: Perspectives and Challenges in Indian English Drama’, Priya Srivastava writes, “Although, the theme of the play is from history, there are many such plays in Kannada, where Karnad’s treatment of the theme is not historical. It throws light on the life, nature and psyche of a medieval monarch, Sultan Mohammad Tughlaq, whose reign is considered to be one of the spectacular regimes of history. Being a sensitive and intelligent ruler who sets out to do the best for his people, Tughlaq was misunderstood and maligned, suffers from an increasing sense of alienation and is forced to abandon his earlier idealism and end up as a tyrant.”

Quoting American novelist Edmund Fuller’s lines, Srivastava writes, “Man suffers not only from war, persecution, famine and ruin, but from inner problems... a conviction of isolation, randomness (and) meaninglessness in his way of existence.”

Ebrahim Alkazi made the play more popular by staging it in Delhi with the grand Purana Qila as the backdrop and his student Manohar Singh reliving the character of Tughlaq.

“The pervasive sense of alienation has corroded human life from various quarters and the man has shrunk in spirit languishing in confusion, frustration, disintegration, and disillusionment and alienation. Spirit of this understanding is the crux of Karnad’s Tughlaq, which is not just an ordinary play chronicling history, but it is an imaginative reconstruction of history in the modern context.”

Many such articles have been written about Tughlaq, widely recognised as a classic over the past 60 years. Still the play continues to intrigue the new generation.

Inspiration for Karnad to write Tughlaq

According to Karnad’s own admission, he sat befuddled with the complex structure and confusing characters, after completing the writing of Tughlaq. He gained confidence, when noted scholar AK Ramanujan and literary critic Keerthinath Kurtakoti read and appreciated the play.

It was noted literary and cultural critic Keerthinath Kurtakoti’s introduction to Nadedu Banda Daari — an anthology tracing the development of Kannada literature — that forced Karnad to write Tughlaq.

Karnad recalled the creative progression of writing this play in Aadaadtha Aayushya —memoirs of Karnad — translated by Girish Karnad and Srinath Perur into English as This Life at Play. In his introduction Keerthinatha Kurtakoti, observed: “In Kannada plays, no one has attempted to use historical material to try and reveal new layers of truth. Along with resurrecting the past, we need to develop a vision that looks at the past in a new light. We need new works that use the raw material of history.”

On reading this short paragraph, Karnad thought, such a play was worth attempting. He started poring over history books. Karnad found the material he was looking for in the 14th century Indian history; the ‘mad’ reign of Muhammad Tughlaq. He was always fascinated with the existentialist angle in texts. Albert Camus’s Caligula was among the plays he was thinking of while writing Tughlaq.

Influence of Ivan the Terrible

It is also being argued that Karnad might have been influenced by Ivan the Terrible, one of the most outstanding personalities in Russian history, who transformed Russia from a medieval State into an empire with a centralised government in 1547.

However, according to theatre analysts, who wrote extensively on the play, Karnad in his play has shown Tughlaq as a man of many contradictions, the ideal and the real, the aspiring and the intriguing. Tughlaq was an idealist, who wanted to treat Hindus as human beings, but in reality Hindus also dislike it, because they suspect the intention of Tughlaq. He wants justice and brotherhood in his country. He wants justice to work in his kingdom without any consideration of might or weakness, religion or creed. He craves for equality, progress and peace. Another distinctive feature of this play is its exploration of man’s search for power and what he can do to attain it.

To create his ideal society, he wants to transfer the capital of his empire from Delhi to Daulatabad and rationalises the decision saying, “Delhi is too near the border and you know its peace is never free from the fear of invaders. But for me the most important factor is that Daulatabad is a city of the Hindus and as the capital it will symbolise the bond between Muslims and Hindus, which I wish to develop and strengthen in my kingdom. I invite you all to accompany me to Daulatabad. This is only an invitation and not an order. Only those who have faith in me may come with me. With their help I shall build an empire which will be the envy of the world.”

Jnanpith Award recipient writer UR Ananthamurthy in one his articles says that Karnad’s Tughlaq should be studied to find parallels between the realities of the fourteenth century India ruled by the sultan and the twentieth century democratic country governed by the Prime Minister and his colleagues in the Cabinet.

“What struck me about Tughlaq’s history was that it was contemporary. The fact that he was the most intelligent king ever to come to the throne in Delhi, and one of the greatest failures also. And within a span of 20 years this tremendously capable man had gone into pieces. This seemed to be both due to his idealism as well as the shortcomings in him. Such as his impatience, cruelty, his belief that only he had the only correct answer. And I felt in the early 1960s, India had also come very far in the same direction. The 20-year period seemed to me very much striking parallel.”

Another instance in which Tughlaq seemingly allowed ego to get the better of reasoning is his sudden change of currency, a move mirrored in the demonetisation plan of 2016. Tughlaq says, “From next year, we will have copper currency in our empire along with the silver dinars.”

What this did was make way for counterfeiting, serving a jolt to the economy and proving to the masses that Tughlaq lacked vision.

“People did not trust his plans and began to see him as an eccentric Sultan. This created further alienation from society,” argues Priya Vatsava.

In the play, after the failure of not realising the dream of an ideal society, Tughlaq turns into be a tyrant. He commits sins and turns corrupt. But eventually he gets tired and wants to sleep.

“I am suddenly feeling tired. And sleepy. For five years, sleep has avoided me and now suddenly it is back,” he tells Barani.

This hints at a kind of frustration that envelopes every individual who confuses his ‘ego’ with ‘idealistic ambition’. This frustration is common to every over ambitious soul.

Political allegory

According to many critics, Tughlaq is a political allegory. In the play, power and politics are linked with religion, like the way it is happening in recent years. Critics say Tughlaq’s alienation from traditional religion arises primarily from the fact that he is an existentialist in his religion and therefore inevitably comes into conflict with the orthodox believers and fundamentalists in religion. Of course, Karnad consulted many renowned historians before writing the play. Though he used all historical resources at his disposal, he extracted what was necessary for artistic and technical purposes. That’s where he excels as a playwright.

Karnad was drawn to critical aspects of Tughlaq. First, despite being the most brilliant sultan to sit on the throne of Delhi, he came to be regarded as ‘mad’ by both his contemporaries and in posterity. Secondly, Tughlaq forbade public prayers for nearly five years of his reign. Karnad understood that this decision of Tughlaq had its origins in the struggles with religion.

Two years before he sat down to write Tughlaq, Karnad made a noting in his diary, “When it comes to washing away filth, no saint is a match for a dhobi.” Later, he included the line in the last scene of Tughlaq.

He earlier wanted the play to resemble a traditional professional theatre form, and so the characters Aziz and Aazam were modelled on epic Ramayana’s Akara and Makara. When Aziz grew in stature and became an independent character, Karnad was in a state of confusion and didn’t know how to proceed. It was his friend Krishna Basarura who told him in 1962, when the two met in Paris, to make Aziz confront Tughlaq. “All in all, I struggled for around two years to finish Tughlaq,” Karnad said.

This is precisely why Karnad dedicated the play to Krishna Basarura. Though Karnad wanted to credit Krishna Basarura as co-author, the latter refused to accept the credit.

First translation

It was Indian theatre doyen BV Karanth, who translated Tughlaq from Kannada to Urdu and renowned theatre and film actor Om Shivpuri, who adapted Tughlaq to theatre and staged it at ridges of Talkatora Gardens, New Delhi.

Ebrahim Alkazi made the play more popular by staging it again in Delhi with the grand Purana Qila as a backdrop and his student Manohar Singh reliving the character of Tughlaq. Alyque Padamsee asked Karnad to translate Tughlaq into English and staged the play with Kabir Bedi in the lead role. Vijay Tendulkar translated the play into Marathi. Shyamanand Jalan directed Tughlaq for Bangla theatre group. Stalwarts of Indian theatre, Shambhu Mitra and Ajitesh Banerjee essayed characters of Tughlaq and Aziz.

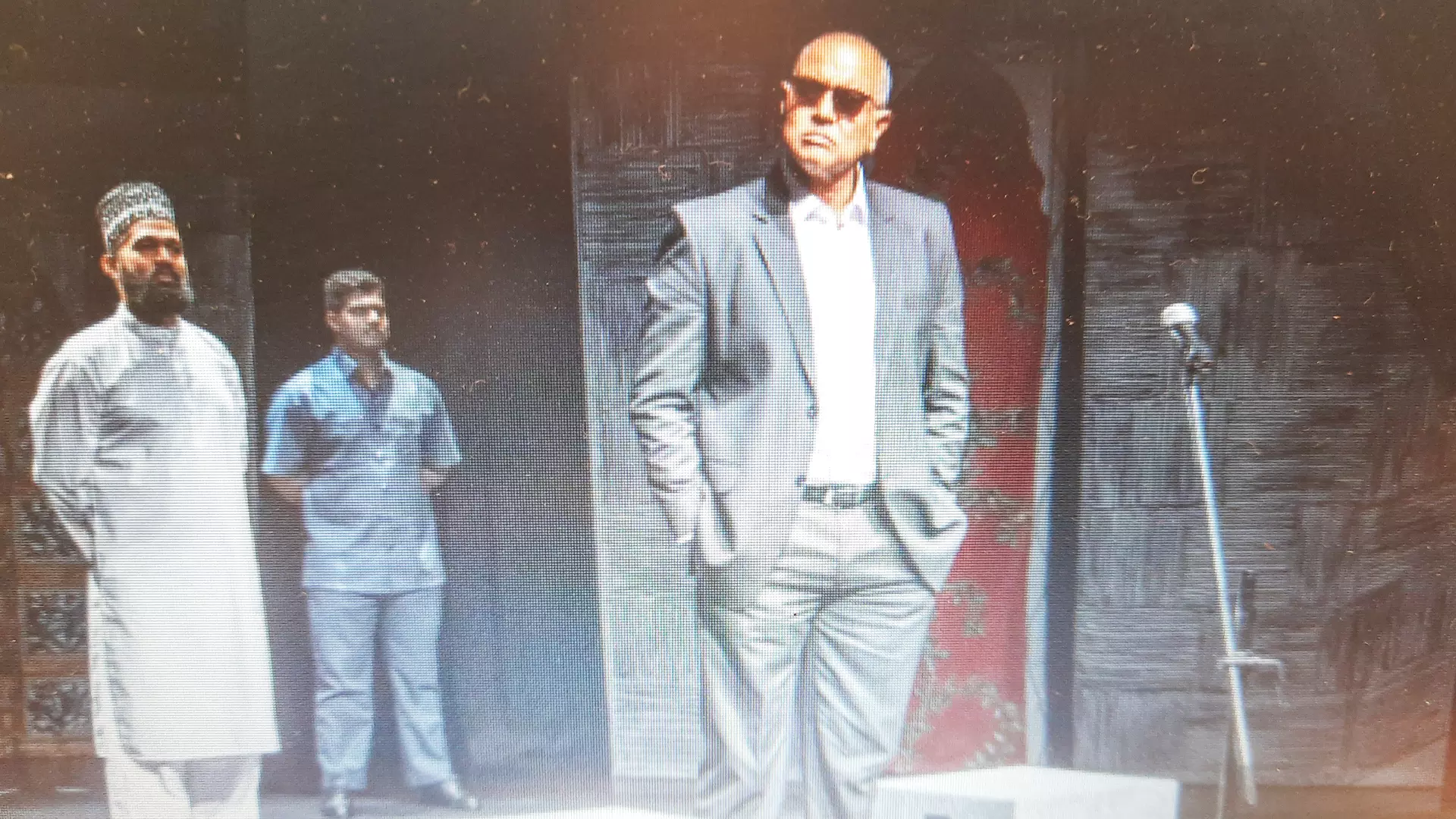

Actor Kabir Bedi as Tughlaq. Late Alyque Padamsee had asked Karnad to translate Tughlaq into English and staged the play with Kabir Bedi in the lead role.

While the play gained popularity in India, it was banned in Sri Lanka and had to be played secretly in Pakistan under the rule of Muhammad Zia-Ul-Haq by a theatre group because it created a sense of insecurity among the narcissist political leaders in Asian countries.

Tughlaq was staged in Kannada, five years after it was published. Noted theatre artist, film actor and director CR Simha essayed the character Tughlaq in the play directed by Prof B Chandrashekar, a distinguished name in Kannada theatre and active member of Bangalore Little Theatre. Prof BC chose the best artistes from 13 major theatre groups of Bengaluru keeping in mind the vast canvas of Tughlaq.

The play was staged in Ravindra Kalakshetra, epic centre of Kannada theatre in 1969. According to theatre personality Ha Sa Krishnamurthy, the play ran to full house for three shows, which even today is considered a major achievement for Kannada amateur theatre. The play could not be staged for some time. Later, Simha along with theatre personalities including theatre and cine artist Lokesh formed Natarang Theatre Group and staged Tughlaq in 1969. Lokesh essayed the role of Aziz. Nataranga staged 150 shows in capital cities of the country including Bengaluru, Mumbai, Chennai, Kolkata and Ahmedabad.

According to theatre coordinator G Kappanna, Tughlaq was first staged two years after its publication in Mangaluru by Vishukumar, a cine actor in 1966. “He completely made Tughlaq a mythological play with the support of costume trader Budan Sab,” recalls Kappanna.

Recounting the glory of the play, Kappanna said, “We counted the shows of Nataranga till 1996 and then gave up the count.”

“Simha was considered as promoter of Tughlaq in Kannada theatre, as he was involved both as director and protagonist right from 1972 till his death in 2014. Tughlaq and Simha have become synonymous with Tughlaq, the character, as he essayed the role for more than 30 years,” adds Kappanna with a note that every theatre troupe of some salt in Karnataka staged Tughlaq and it is difficult to keep count on the shows the play saw in the past 60 years.

Contemporisation of Tughlaq

It is an indisputable fact that no other play saw the amount of success that Tughlaq did. The feeling of hatred, insecurity and injustice seems to have stuck from the very first scene itself. In that sense, it is more contemporary than ever before. The character of Tughlaq also portrays someone with pluralistic and secularist thinking.

It was TS Narasmihan who tried to contemporise Tughlaq with the help of costumes in late 1970s. In his play, for the first time Tughlaq appeared in modern clothes. A similar attempt was made by S Surendranath recently for Bengaluru-based arts organisation Bhoomija.

In a 1970s depiction of the play, Tughlaq appeared in modern clothes.

It was renowned film and theatre personality MS Sathyu, who designed the play and characters appeared on the stage in modern costumes.

Relevance of Tughlaq

According to theatre and cine personality B Suresh, Tughlaq directed by Surendranath is the most hard-hitting and relevant play among the productions made so far. For Surendranath. Tughlaq is one of the greatest plays of Indian theatre. “This play, which revolves around an eccentric ruler in Indian history and the events of that time, can never be irrelevant. Political strategies, religious intrigues, religio-political conflicts and personal relationships are interlocked in the play,” observes Surendranath, a graduate of National School of Drama, who is one among the most successful and prolific playwrights of modern Indian theatre.

“Our presentation of the play is an attempt to bring it closer to the present socio-political and cultural ecosystem, both inwardly and externally. It inwardly examines Tughlaq’s personal turmoil and his relationships and externally by bringing up contemporary events. It is an attempt to see Tughlaq as a common man rather than as a king, thereby understanding the present in both general and political contexts. It is also an attempt to understand what impact the order of the palace has on the population at large,” says Surendranath.

Samudaya, a cultural movement which fought Emergency imposed by Indira Gandhi in 1975 through cultural activities such as street plays and jathas and reached out to people using theatre as a tool for social change, revived the play in 2014. It recently staged the play’s 98th show in Bengaluru, bringing it closer to the 100-show mark. “Wherever, we staged the play, the response was enthusiastic, especially from the younger generation,” says Shashidhar, executive president of Samudaya.

“Though Tughlaq is a historical play, it is a commentary on contemporary politics. In the play protagonist Tughlaq is portrayed as having great ideals and ideas and a grand vision, but his reign was an abject failure. He started his rule with great ideals of unified India, but it degenerated in to anarchy,” says Dr Sripad Bhat, who co-directed the play with Samkutty Pattomkary.

Blurb that saw the future

As it was Keerthinath Kurtakoti’s article that inspired Karnad to write Tughlaq, what Kurtakoti said in the blurb published on the first edition of Tughlaq gains importance.

“This play is a dramatic representation of an ambiguous stand between wisdom and fatuity. The fundamental issue in the play is the eternal desire of a man with animal instinct to attain the status of divinity. Street larcenist changing costume in accordance with the promulgation of new law, chieftains committing murder when prayer is on and religious leaders, who considers politics as service to god,” observes Kurtakoti in the note.