Architect of unity or right-wing icon? Remembering Sardar Patel's legacy in the New India

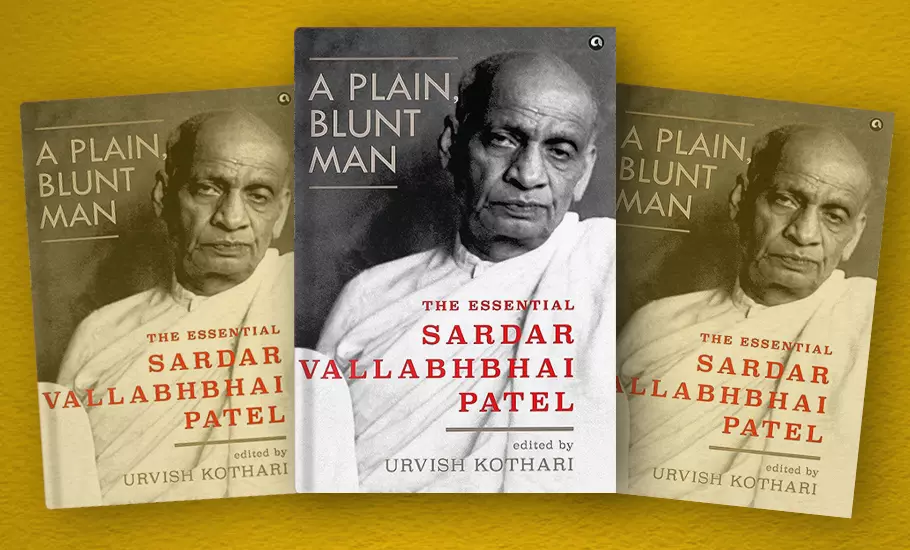

“A Plain, Blunt Man: The Essential Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel,” edited by Urvish Kothari, reveals how Patel's legacy lies in uniting India, in contrast to the Hindutva brigade's intent of dividing it.

“Sardar Patel is a man to remember gratefully in good times and as a benchmark of India’s potential when the times seem depressing or daunting,” wrote Rajmohan Gandhi in the Preface to Patel: A Life (1990), the first complete biography of India’s Iron Man, who is credited with having unified India, saving it from getting fragmented into fiefdoms of 565 princely states at the time of Independence. After Patel, the organiser and the disciplinarian compared to Bismark, died in 1950, a curtain was drawn on his life, with the official India, and the Congress party, distancing itself from one of its erstwhile pillars. While Patel’s daughter, Maniben, remained closely tied to Congress until its split in 1969 under Indira Gandhi's leadership, his son Dahyabhai accused the party of neglecting his father’s legacy and eventually left the Congress fold in 1957.

For long, Patel has been disparaged and discounted as a right-wing leader and an anti-Muslim. At a time when the Sangh Parivar and the ruling BJP is trying to appropriate the right-of-centre ploughboy whom Vinoba Bhave called “the accurate bowman of Mahatma Gandhi’s struggle, his disciple and his general officer commanding,” how do we remember Patel? In A Plain, Blunt Man: The Essential Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, an anthology of his writings (Aleph Book Company), its editor, Gujarati writer Urvish Kothari, sets the record straight early on. Kothari clarifies that though Patel was a staunch Hindu, he was an ardent follower of Gandhi, with faith in Congress party’s inclusive philosophy, who would never subscribe to the far-right ideology, which has come to be known as Hindutva today. Patel, as his other biographers like Balraj Krishna have underlined, was never a man of ideology, but a man of action, of Integrity.

A pragmatist, with disdain for political punditry

A barrister by training but a farmer at heart, Patel was pragmatic, with characteristic disdain for empty speeches and political punditry. As a leader who was part of the Swaraj troika, which included Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, Patel had famously, and unambiguously, said that “the duty of Hindus is to fully help the Muslims” and that “the state must exist for all, irrespective of caste and creed.” Kothari writes that Patel may not have taken care of the sentiments of the Muslims as much as Gandhi and Nehru did, but he neither approved of the crimes of the Hindu nationalists nor did he engage in majoritarian politics, fuelled by hate and suspicion.

Patel held humility, and service to his nation, close to his heart. He believed that he lacked original political ideas and instead dedicated himself to the cause of satyagraha championed by Gandhi. Though he was willing to learn from Gandhi, he had not qualms in saying that the latter was no ‘Mahatma’. Despite his role in creating a well-organised political machinery and a potent election strategy, he remained averse to exploiting power for personal gain. Though he maintained friendships with industrialists, he didn’t utilise their resources to cultivate a cult of personality. Rejecting political ambitions, he gracefully stepped back from challenging Nehru's leadership as the first Prime Minister at Gandhi's behest.

The architect of unity

Though Kothari compiles speeches, articles and letters that showcase various aspects of Patel’s life and work, including his role as a party strategist, administrator and the architect of the integration of the princely states, perhaps it’s his views on communal issues that resonate the most in today’s political climate, with the Saffron brigade hell bent on claiming that he was one of their own.

Citing just two letters Patel wrote to two ideologues of the Hindu supremacists, M.S. Golwalkar and Syama Prasad Mookerjee, is enough to shatter their perception that Patel played the divisive partisan politics. Days after the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, Patel had banned the RSS in order to root out forces of ‘hate and violence.’ He had expressed his concerns about its activities in a letter to M. S. Golwalkar. While he acknowledged the organisation’s positive contributions to society, particularly in protecting vulnerable sections and assisting Hindus, he strongly criticized the RSS for taking a vengeful stance against Muslims and attacking innocent people. Patel also highlighted its intense opposition to the Congress, which had led to unrest and communal tensions. He urged Golwalkar to reconsider the RSS's path and join hands with the Congress for the welfare of the nation, especially during challenging times.

In another letter written to Syama Prasad around the same time, while he refrained from commenting on the role of the RSS and the Hindu Mahasabha in Gandhi's assassination due to ongoing legal proceedings, he believed that they had contributed to creating an environment conducive to the tragic event. “..,As regards the RSS and the Hindu Mahasabha, the case relating to Gandhiji’s murder is sub judice and I should not like to say anything about the participation of the two organisations, but our reports do confirm that, as a result of the activities of these two bodies, particularly the former, an atmosphere was created in the country in which such a ghastly tragedy became possible. There is no doubt in my mind that the extreme section of the Hindu Mahasabha was involved in this conspiracy. The activities of the RSS constituted a clear threat to the existence of government and the state,” he wrote.

“Troubled times engender a longing for the grip on India’s affairs that Patel had. How he acquired that grip is part of Patel’s story,” wrote Rajmohan Gandhi. Today, as a million mutinies resurface in India and as it becomes, in Naipaulspeak, an area of darkness again, how should we remember Patel? If we go by his writings, we know that his legacy is best encapsulated by his unparalleled ability to bring together a diverse and multifarious nation under a single banner. His vision of India was a harmonious mosaic, with each diverse piece contributing to the nation's identity. We should then remember him as a man who, more than anything else, united India, something which Home Minister Amit Shah has miserably failed to do as Manipur continues to burn and as communal conflagrations singe India’s secular character.