Talks, strikes, delays: Why wage revision is always a challenge at public sector banks

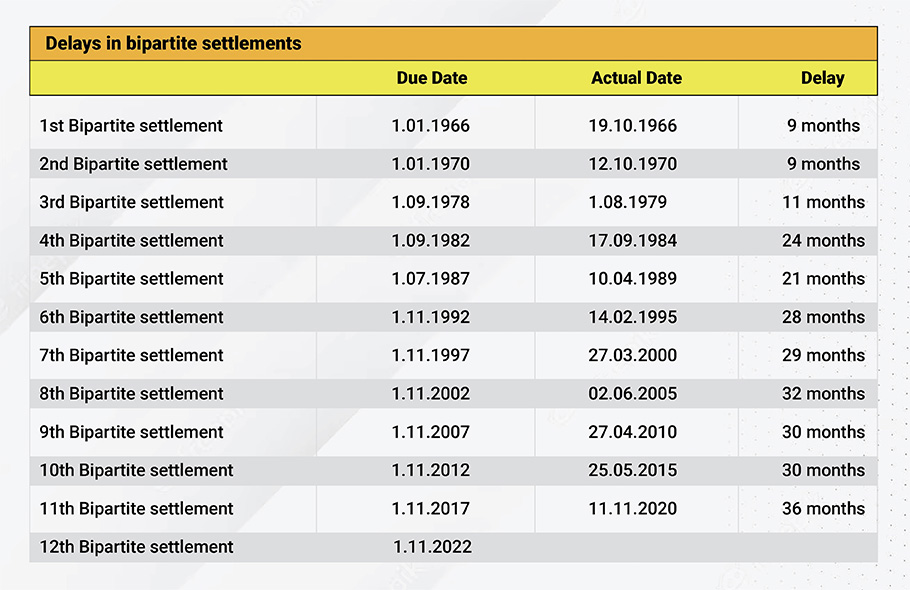

The government has reportedly asked the Indian Banks’ Association (IBA) to start negotiations for the 12th bipartite settlement in a time-bound manner and finalise it by December 1, 2023. The wage revision for employees and officers of public sector banks is due from November 1, 2022.

The Finance Ministry has also asked the IBA to ensure that all future wage negotiations are finalised before the beginning of the subsequent period so that the wage revision can be implemented from the due date itself.

Since 1966, wage revision and related terms and conditions of bank employees have been settled through negotiation between bank managements represented by the IBA and the employees’ unions. The unions generally submit a charter of demand to the IBA, which starts the process of negotiation.

Also read: FM nudges PSU banks to take swift action against frauds, wilful defaulters

Wage settlement for banks has always been a tedious and time-consuming process, with bank managements, represented by IBA, and employees’ unions engaging in tough negotiations. Historically, delays of two or three years in wage settlement have led to a substantial accumulation of arrears, which are eventually disbursed in a lumpsum. Even the present settlement has already been delayed by more than nine months (see table on delays of earlier settlements below).

We also see protracted agitations, including strike calls by employees to achieve their demand. Unions and banks usually blame each other for the tardy process of settlement. But it has an economic cost. Unrest in the banking industry will affect growth of economy.

Why the delay?

Any union worth its credibility will try to get the maximum for the employees, and bank unions are no exception. Hence, the demand will generally be higher. For example, though the unions know quite well that the management may not concede a 20 per cent increase in wages, they will put forth a demand to that effect. The IBA’s attitude is no better. For instance, during the last wage negotiation, the IBA initially offered a mere 2 per cent increase, which was ridiculous. Finally, the settlement was reached at 15 per cent increase in pay slip.

The IBA gets a mandate from the banks to negotiate on their behalf. However, it is not empowered to decide on their own. The IBA makes frequent consultations with the government to go forward. This delays the process.

Like any other industry, the wage settlement in banks is also linked to earnings and profitability of banks. However, the banks do not operate strictly based on the concept of maximization of shareholder value. They have to serve society by financial inclusion. They extend priority sector credit at concessional rates of interest. They open branches to serve society where the operations may not be profitable.

Also read: Strong performance of Indian banks to continue: S&P

Banks’ major earnings come from the interest charged. But the interest rates are guided by policy rates of RBI, and the RBI considers inflation, growth, desired liquidity, government borrowings, etc., to decide on the policy rates. Hence, it may not be fully correct to link wages and the profitability of banks, but the government of the day always connect the two.

When wage settlement is delayed, arrears are paid after each settlement, and the employees get two or three years’ arrears. They get a lumpsum, and the unions collect a percentage of such arrears as levy. During the last wage settlement, when the negotiations were on, the IBA unilaterally directed banks to release a lumpsum as an interim measure. Strangely, the unions objected to it, probably due to the cut in the levy.

A changed scenario

Of late, the management has been taking a tough posture, as we saw with the 2 per cent hike offer in the last settlement. Three or four decades ago, the “collective bargaining” concept meant that the managements would bargain, but ultimately, the unions would collect.

But gone are those days. With core banking and various delivery channels, like net banking, ATM, UPI, NEFT, RTGS, etc. introduced, many transactions can happen in banks even without employees’ presence, and unions cannot paralyse banking operations.

Also, private sector banks like ICICI Bank, HDFC Bank, etc. continue to provide full services when public sector bank employees go on strike. With all these developments, employees’ strikes are no longer all that effective and bank employees have lost their bargaining power.

Banks are the backbone of our economic system. Hence, it is necessary to attract and retain talent in banks, and this is possible only with conducive working conditions. The compensation package is an important tool to achieve this. The government’s suggestion to complete wage settlement in banks on time is therefore a timely one.

Also read: Public Sector Banks’ profits cross Rs 1 lakh crore mark in FY23

Public sector versus private sector

It is undeniable that public sector banks are losing their share of business to new-generation private sector banks. The credit shares of public sector banks have come down compared to private banks operating in the same bracket, a report by the Reserve Bank of India states.

Data released by the central bank showed that in March 2022, public sector banks’ share in the total credit by scheduled commercial banks stood at 54.8 per cent in March 2022 compared to 65.8 per cent five years ago and 74.2 per cent 10 years ago.

Even on the deposit front, PSBs’ market share dropped to about 62 per cent in March-end 2022 against 66 per cent in March-end 2019.

However, the compensation package is also entirely different for private banks. They have a system to reward performers but in public sector banks, all are put on a uniform pay scale. Public sector bank employees also face the vigilance machinery, like Central Vigilance Commission, CBI, etc., which oversee their decision-making process, which makes them cautious.

Even at the highest level, the compensation package of public sector banks is far less than that of private banks. Dinesh Khara, chairman of India’s biggest government bank State Bank of India, took home Rs 37 lakh in the 2022-2023 fiscal year. Compare that with Sandeep Bakhshi, the CEO of ICICI Bank, who takes home an annual salary of around Rs 7.08 crore. Or, Amitabh Chaudhry, Managing Director of Axis Bank, the third-largest private sector bank, who earns an annual salary of Rs 6.01 crore.

Also read: RBI governor Das warns banks on asset-liability mismatches

The wage revision talks continue only in the traditional way, and there do not seem to be any effort to address these challenges to public sector banks. It would be in the fitness of things if banks and unions try to achieve the best talent and performance with the best compensation package.

(The author is a retired banker.)