Linking Ken-Betwa rivers will cost 46 lakh trees! Anybody listening?

The project, announced in the Budget, has no statutory clearance, and poses a major risk to a tiger reserve and the region's biodiversity

On April 13, 2015, the Ministry of Water Resources constituted a task force for the Interlinking of Rivers (ILR) programme — Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s dream project. Modi borrowed the dream from former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, who had first drawn elaborate plans to link rivers, in 2002.

On February 1, 2022, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman presented Budget 2022 and declared the Ken-Betwa Link Project at a whopping cost of ₹44,605 crore.

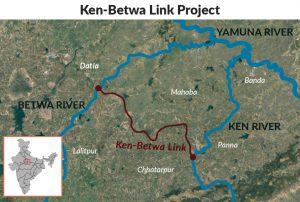

As proposed, the project aims to transfer water from the Ken to the Betwa, both tributaries of the Yamuna, using a link canal that will be 221 km long, including a 2-km-long tunnel.

The FM threw out lofty numbers to justify the benefits of the ambitious project: irrigation for about 1 million hectares of agricultural land, drinking water for 6.2 million people, 103 MW of hydroelectric and 27 MW of solar power, among others.

Lack of statutory clearance

What the FM did not mention is the lack of statutory clearances for the project. “It doesn’t have final forest clearance, its environmental clearance is currently under challenge before the National Green Tribunal (NGT) and the project’s wildlife clearance has been declared invalid by a Supreme Court committee,” Himanshu Thakkar of the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP) told The Federal.

“Forget about the merit of the Ken-Betwa link project, the process bottlenecks are too big a hurdle to cross,” added Thakkar, who was part of the Water Resources MInistry’s expert committee on interlinking of rivers.

He further said the project is being pushed on the assumption that the Ken has excess water and the Betwa, less. “I asked the government — please tell me the hydrological calculations on the basis of which you claim the Ken has excess water and the Betwa has a deficit of it. I was told it is a state secret,” said Thakkar.

Also read: Want to save water? Know your water footprint first

A new study has determined that the Ken-Betwa link project will lead to a large portion of the Panna Tiger Reserve in Madhya Pradesh going under water, which essentially means loss of habitat and prey for the tiger.

Damage to tiger reserve, biodiversity

Around 58 sq km of the land area, or 10% of the tiger reserve, will be lost if the project is implemented. The indirect loss could extend up to 105 sq km because of habitat fragmentation and loss of connectivity due to submergence, said a study published in the December 2021 edition of Current Science.

It would mean a primary loss of some 23 lakh full-grown trees (trunk girth of 20 cm or more) and about 23 lakh more trees over the next eight years. Thus, a loss of 46 lakh trees and associated diversity. And these are not mere plantations, but vegetation of jungles that protect biodiversity.

Additionally, with the loss of lakhs of trees, the hydrological cycle of the land will be impacted. Exposing 58 sq km of land to the sun would deplete the groundwater table of the region, because jungles are very good at harvesting rain water. “Have the hydrological implications of the river-linking project to the drought-prone region of Bundelkhand been thought of?” asked Thakkar, who has extensively studied river-linking projects.

The Ken-Betwa River Interlinking (KBRIL) Project promises to transfer excess water from the Ken to the Betwa to irrigate the drought-prone Bundelkhand region, but does the Bundelkhand region need this water? “The government wants to build dams in the Upper Betwa basin, but this would dry up the dams in the lower Betwa basin. So, as a compensation to the reduced flow of water to dams in the lower basin, this financially and environmentally untenable river-linking project is being given shape,” observed Thakkar.

Experts say the project has already been delayed by more than two decades and is still far away from implementation with all the legal hurdles it has to cross further. However, big announcements such as the recent budgetary one make sense when one looks at them through the prism of the upcoming Uttar Pradesh Assembly election.

Characteristics of rivers

Manish Ghorpade, founder-director of Jeevitnadi, an NGO dedicated to the revival of rivers in Pune, said: “When it comes to river interlinking, I believe both blanket opposition and blind support are incorrect. I remember when the Panchganga river in Kolhapur got flooded, diverting its water to a smaller river worked well. Of course, it was a one-off example. To do it on a large scale and on multiple rivers requires understanding the characteristics of each river, its nature and its biodiversity.”

Also read: Major push for solar energy & EVs, little for climate change, forests

“Mixing the water of one river with that of another may not be suitable to a particular kind of fish which could be endemic to that particular river. Linking rivers without an in-depth environmental assessment may trigger a change which could alter the characteristics of the river, like its flood level, meanders, erosion levels, silt depositions, etc,” he told The Federal.

Besides the Ken-Betwa project, Sitharaman said the draft detailed project reports of five river links have been finalised: Damanganga-Pinjal, Par-Tapi-Narmada, Godavari-Krishna, Krishna-Pennar and Pennar-Cauvery.

In reality, only the draft development project reports (DPRs) have been okayed. In the absence of agreements, the projects may not see the light of the day for many more years. Neither the Godavari nor the Krishna has surplus water. For that matter none of the above mentioned rivers has any water to spare that can be fed into canals. So how can any of the river-linking projects succeed?

Political gains

Micro projects aimed at conservation of water have seen success of late. Most of these efforts are low on cost and technology, and are suitable for local community-level implementation. But what they lack is the lure of the big money.

As Ghorpade of Jeevitnadi said, “Politicians want an idea that can be sold to the masses. The restoration of a barren land that resulted in the conservation of biodiversity doesn’t make a big headline. Yes, declaring a multi-million dollar plan that promises drinking water to 62 lakh people does.”