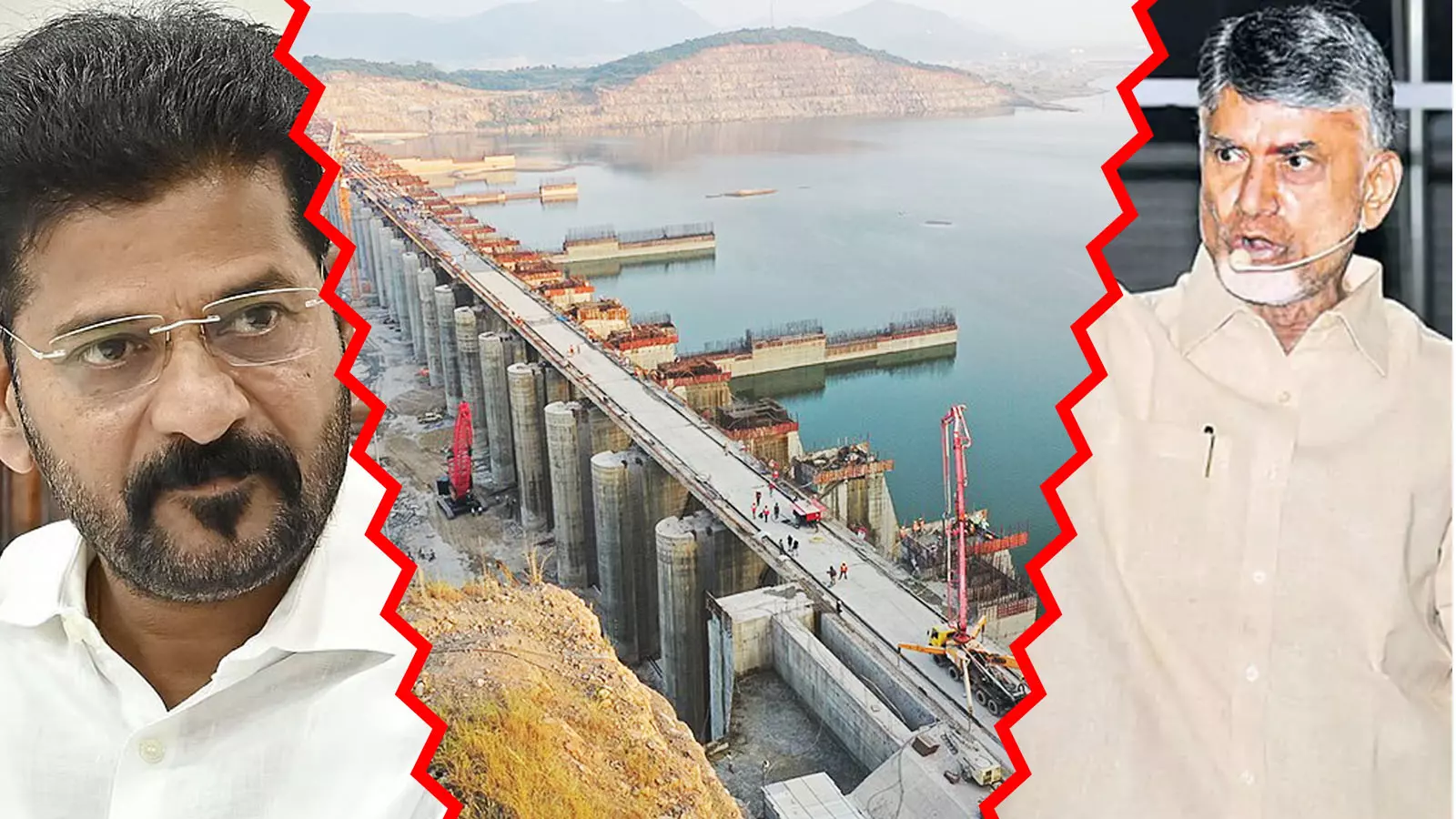

Andhra's new Polavaram plan puts it on collision course with Telangana

Chandrababu Naidu calls it a lifeline for Rayalaseema, Revanth Reddy calls it a violation of the 2014 Reorganisation Act, but experts say it may not even work

Neellu (water) was one of the three core slogans that drove the Telangana statehood movement, apart from nidhulu (funds) and niyamakalu (jobs). Yet, more than a decade after Telangana's formation, water has become the centre of a bitter dispute with Andhra Pradesh.

The controversy stems from Andhra's Polavaram-Nallamala Sagar link project, which aims to divert 200 TMC ft (thousand million cubic feet) of Godavari floodwaters to the state's drought-prone Rayalaseema region. Chief Minister Chandrababu Naidu has championed the project as crucial for drinking water, irrigation and industrial use.

Ironically, the dispute has intensified just a month after both chief ministers publicly played down tensions. Naidu had said he wasn't ready for water-sharing disputes with Telangana, citing their common Telugu identity. His Telangana counterpart Revanth Reddy echoed similar sentiments, expressing a preference for dialogue. The matter, though, looks far from settled.

Telangana's objections

Telangana argues the project violates the Andhra Pradesh Reorganisation Act of 2014, which bifurcated the state, and lacks clearance from the Godavari and Krishna river management boards constituted under the same act.

What are riparian rights?

These are the legal rights of landowners whose property adjoins a natural watercourse (rivers or streams) to reasonable use of that water, access to the shoreline, and the right to accretion.

The state's primary concern is that Andhra will establish riparian rights over the water once the project is approved. Telangana wants Andhra to first withdraw objections against its own projects—both planned and under construction—before any water allocation agreement.

Of the 1,499.9 TMC ft annual share allotted to undivided Andhra Pradesh, the residuary Andhra already uses its 531.9 TMC ft allocation. Telangana's 968 TMC ft share remains largely underutilised due to infrastructure constraints.

Fair share

V Prakash, who served as adviser to former Chief Minister K Chandrasekhar Rao and chaired the Telangana Water Resources Development Corporation, said the allocation was based on ongoing, contemplated and existing projects combined. The share of the landlocked state was established at the time of undivided Andhra Pradesh, he recalled."

AI-generated vector diagram shows the rivers, the Polavaram project site, and the proposed, disputed link to Nallamala Sagar.

“The figure was arrived at by the Kiran Kumar Reddy (the last CM of undivided Andhra) government based on utilisation,” he told The Federal. "The allocation is for the ongoing, contemplated and existing projects put together. Once this is done, Telangana will not have any objection to the construction of projects by Andhra for its own share."

The Godavari Water Disputes Tribunal puts the total availability of water at 75 per cent dependability for the seven basin states at 3,396.9 TMC ft a year. The states are Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, and Karnataka, besides Telangana and Andhra.

Surplus water claims

While Naidu argues the project is based on 3,100 TMC ft of annual runoff that flows into the Bay of Bengal—water allocated but unused by riparian states—experts disagree.

Sriram Vedire, water resources adviser to the Maharashtra chief minister and former adviser to the Union Jal Shakti Ministry, said the average water flowing into the sea is just around 1,138 TMC ft annually.

"The two Telugu states have no right over this water," he said, adding that without Central Water Commission confirmation, no project can be constructed on these "imaginary flood waters".

Prakash pointed out that Telangana hasn't even utilised 400-500 TMC ft of water, yet Andhra has objected to several Telangana projects, such as the Sitarama, Sammakka, Medigadda and Wardha projects in Asifabad.

He added that there is no concept of surplus water in the Godavari like there is in the Krishna.

Bachawat Award complication

Mereddy Shyam Prasad Reddy, a former executive engineer in Telangana's irrigation department, believes the Polavaram project will ultimately prove futile for Andhra.

The Bachawat Award of the 1970s gave Maharashtra and Karnataka rights to retain more Krishna water if lower-riparian Andhra taps more Godavari water. If Andhra proceeds with Polavaram, nearly 88 TMC ft of water can be retained by these upper-riparian states.

"The 112 TMC ft of water has to be utilised upstream of Nagarjuna Sagar. Now that Telangana is a separate state, it will claim its share of nearly 80 TMC ft," Reddy said.

Feasibility concerns

Beyond legal issues, the project faces practical challenges. The Naidu government initially planned to link the project with Banakacherla, but shifted to Nallamala Sagar to avoid excavating a 26-km tunnel through the environmentally sensitive Nallamalla Wildlife Sanctuary.

The Central Water Commission has said it will examine the issue only after the Godavari River Management Board submits technical feasibility reports—a step Andhra bypassed by approaching the Jal Shakti ministry directly.

Veteran journalist V Sankaraiah, speaking to The Federal, questioned Andhra's financial capacity, noting the state hasn't completed the centrally funded Polavaram project itself.

Alternative approach needed

Experts stressed the need for better water use efficiency. In Telangana, one TMC ft irrigates 10,000 acres of paddy fields; in coastal Andhra, only 3,000-4,000 acres. Canal system efficiency stands at just 30 per cent.

Mereddy Reddy and Sankaraiah advocated for rainwater harvesting, contour trenching, minor irrigation tanks and check dams over large projects. "With just around Rs 12,000 crore, an entire state can be recharged," the former said, citing Maharashtra's Hiware Bazar village as a successful water conservation model.

The dispute underscores the complex water-sharing challenges facing India's riparian states, where political ambitions often clash with technical realities and environmental concerns.

(The article was originally published in The Federal Telangana.)