- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Zero death milestone: Is the nightmare really over for Mumbai?

When the pandemic first struck India in March 2020, very little was known about coronavirus apart from the fact that it originated in China, was zoonotic and could even kill people if they came in contact with infected persons. In overcrowded Mumbai though, what people didn’t know was how not to come in contact with people. With a population of over 1,20,00,000 and a geographical area of 437...

When the pandemic first struck India in March 2020, very little was known about coronavirus apart from the fact that it originated in China, was zoonotic and could even kill people if they came in contact with infected persons. In overcrowded Mumbai though, what people didn’t know was how not to come in contact with people.

With a population of over 1,20,00,000 and a geographical area of 437 sq km, every Mumbaikar was in the breathing range of another. Town planners say that is because barely 120 sq km is the actual habitable residential area for the 12 million or 1.2 crore people. When space comes at a premium, the poor are the natural losers. Asia’s largest slum, Dharavi, with an area of just over 2.1 square kilometres and a population of about 1,000,000, had 2,77,136 people struggling to find their feet per kilometre.

The Maximum City recorded the highest number of deaths in Maharashtra with a total of 16,255 people succumbing to the virus so far. So, when on October 17, the city marked its first zero-Covid-death day in 17 months, people literally breathed a sigh of relief.

With cases climbing down, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), which has been at the forefront of Mumbai’s fight against Coronavirus, allowed reopening of places of worship starting October 7. Mumbai has also significantly reduced the restrictions on schools, colleges, restaurants, cinema halls and travel in local trains.

The city is where it is today because of the concerted efforts of public health officials, doctors, civic body representatives, and above all, Mumbaikars, who together fought the virus over the past year and a half.

Recalling the horror

Dr Kusum Gupta, who was in-charge of a 350-bed covid care centre in the densely populated western suburbs of Andheri during the initial stages of the pandemic, says: “It felt like the horror would never end. As soon as it began to look like we had things under control, the second wave hit us. People were unable to find beds and get access to oxygen cylinders. It was as if all the despair from the first wave had come back to hit us.”

Posted at Seven Hills Hospital during the first wave, Gupta moved on to work at the centre located inside Laxmi Industrial Estate in Andheri West. Once this centre was shut down due to a decline in cases, she was posted at the Jumbo Covid Care Centre in Dahisar and then deployed at a BMC war room. She handled another posting at a 150-bed covid care centre and is currently working at a health post in Malad.

Speaking about what changed for the doctors from the first to the second wave, Gupta says: “In March 2020, there was no proper planning done to combat the virus and keep it in check. Basic hospitals such as Shatabdi, Cooper, KEM and Nair were the only ones serving patients during the initial stages of the first wave. Private hospitals were largely hesitant.” It was only towards the end of the first wave, she adds, that the city got infrastructure facilities such as the multiple COVID-19 jumbo centres.

“When the second wave hit us, we already had the infrastructure in place to rely upon. Despite that, the jumbo centres filled up in no time. We found ourselves back to square one.”

According to Gupta, by the end of the first wave, a lot of the smaller Covid care centres were shut down due to a decline in the number of cases. By the time the second wave hit the city, both private and public hospitals had shut their dedicated Covid wards. Suddenly, the jumbo care centres that were set up during the first wave were overburdened. Cases escalated very quickly due to the rampant spread of the delta variant and casualty counts in hospitals rose exponentially. “There was a much heavier death toll than we had anticipated during the second wave.”

How Mumbai reached zero death milestone

Gupta says proper planning and management at the ward level has helped the city. “Health posts belonging to different wards conduct contact-tracing, provide counselling besides creating awareness.” The city recording zero deaths cannot be attributed to just one factor—it is a concerted effort by all those involved, civilian and health professionals alike, she adds.

The one thing that has played the most important role in all of this: the vaccine. Gupta’s father, who suffers from diabetes and other ailments, was diagnosed with COVID-19 a few months ago despite having taken the vaccine. “Taking the vaccine doesn’t mean that you won’t test positive—it means that your body has a higher chance of fighting off the virus that is growing inside it,” she says. “My father had taken the first jab which is why he wasn’t critical.”

Mumbai started its vaccination drive in January. so far, more than 80 per cent of the population has received their first dose and nearly 50 per cent people are fully vaccinated.

Snehal Deshpande is one of them. She was a first-year resident doctor at the state-run JJ Groups of Hospital located in South Mumbai when the pandemic first broke out last March. Today, she is in her third year at the hospital’s Internal Medicine Department.

“Initially, when we came to know about Covid in India, we did not create any facilities or infrastructure,” she says, adding that dedicated jumbo care centres started cropping up in the city around the same time the JJ Group of Hospitals converted its hospitals into Covid centres.

“Both St George Hospital and GT Hospital are a part of the JJ Groups of Hospital. These two hospitals were converted into Covid centres so that JJ Hospital could be kept completely Covid-free. Keeping the hospitals separate helped prevent transmission.”

Deshpande says the second wave was easier to handle, but at the same time was quite taxing due to the presence of new and unforeseen complications.

Although there could be an impending third wave, she feels Mumbai is much better equipped now. “Also, the severity of cases is also much lesser. Patients coming in for treatment are not as sick. Most importantly, people’s outlook towards Covid patients has changed for the better. They themselves are coming forward to get tested.”

Lastly, the vaccine has greatly helped the fight against coronavirus, she adds. “We have indeed come a long way.”

Dr Anuj Tiwari agrees. The assistant professor at the BMC-run Cooper Hospital—one of the biggest and busiest hospitals in the western suburbs—says that the city was unprepared for both the waves. “We were unprepared and had a very poor understanding of the disease the first time around. But by the time the second wave hit us, a lot of us had contracted the virus ourselves. Hence, we were a bit fearless.”

Compared to the first wave, Tiwari adds, the second one was more brutal and disappointing because the death toll was very high. “Despite a fair understanding of the disease, we were unable to do much. I feel the first wave was a slow learning process. Because of the lockdown at the time, the rise in the number of cases was very slow during the first wave.”

Cooper Hospital opened its first Covid ward last April. “The number of cases was high from the beginning,” he says, adding that over the next few weeks, the hospital had to keep increasing the Covid wards it had.

“We were housing 300-400 Covid positive patients at any given time. But the main catch was that Cooper was one of the only hospitals in the city that was catering to both—Covid and non-Covid patients.”

Like other hospitals, Cooper did not shut its services for non-Covid patients. KEM, Sion Hospital and Cooper remained the top tertiary care hospitals that catered to both categories during the pandemic.

Looking back, Tiwari says the worst is possibly behind us. “We are in a much better place right now. The most important contribution towards Mumbai recording zero covid-related deaths goes to the vaccine.”

He also has a word of praise for the BMC. “The moment their war rooms were set up, the coordination was impeccable. We are in a much better place right now.”

VP Mote, former assistant municipal commissioner of Ward-KW of Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai, says all this was possible because of the preventive, curative, and precautionary measures laid down by the BMC—and followed by Mumbaikars. “Together, we have brought the city out of the darkness into the light.”

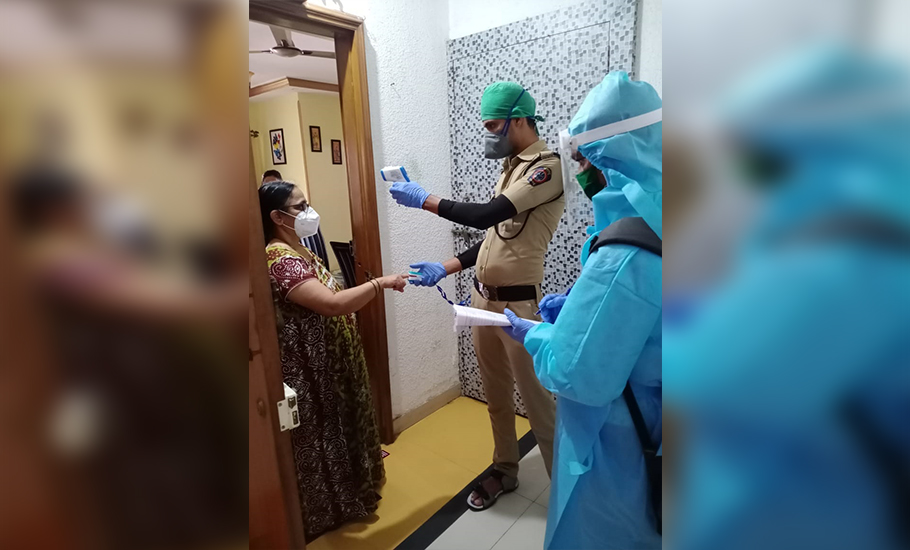

According to Mote, Mumbai poses a different and wider array of problems while combatting the pandemic, primarily due to its demographics oscillating between extremes of slums and high-rise buildings. “We tackled the coronavirus issue in slums through the ‘My Family, My Responsibility’ campaign wherein we made the residents aware of the disease and the precautions to take. What we noticed was that people living in the slums were responding much better to us than those living in highrises.”

The main challenge we faced from those living in highrises was the fear that BMC officials would take them away to quarantine centres. “We had to assure them that as long as they had a separate bathroom and bedroom at home, which most of them do, they don’t need to go to a quarantine centre. We approached the chairmen and secretaries of buildings and encouraged them to be the voice of reason for their society members and to lead by example. It was only after getting rid of these fears that people living in buildings were finally able to trust us.”

It is this trust that has led many to believe that it’s safe to resume normal lives. However, many others are still worried about an impending third wave despite the ‘zero death milestone’.

Is Mumbai dropping the guard too soon?

In New Zealand, authorities investigating a small outbreak in September 2020 found it took just a 50-second window of time when one infected person likely breathed infectious particles into a hotel corridor, leading to two people in the room next door contracting the virus. Even more proof that, given the right conditions, coronavirus only needs a tiny window to create an outbreak.

Virologist Dr Gagandeep Kang, who is a member of the Covid-19 working group and professor at Christian Medical College, Vellore, maintains a large third wave with the existing variants is unlikely but the possibility of small waves limited to certain geographies cannot be ruled out.

While today’s achievements would not have been accomplished without undergoing the stringent learning curves faced during both waves, the real question, according to Dr NK Ganguly, is how many tests have been conducted in Mumbai so far.

Speaking to The Federal, the former Director-General of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) said not enough Mumbaikars are getting tested.

“Instead of getting tested or seeking medical help, people are treating themselves if they exhibit symptoms. The zero deaths recorded could also be possible because there are so many deaths out there that are not attributed to Covid but to some other reasons.”

Dr Ganguly added, “There might even be pending cases from that day which were not counted in the tally for last Sunday. So, if there are so many examples of Covid cases not being counted, we can’t really say that Covid cases and the number of related deaths have come down. They have come down because testing has come down. People choose to sit at home instead of getting treated.”

Even though he agreed that there has been considerable progress, he is worried that thousands of cases are still being reported every day. “A few cases from China spread the disease throughout the world. Therefore, it is dangerous to have even a few cases coming up every day.”

When asked what was in store for the city over the next few months as it steps into the festive season, Ganguly urged everyone not to drop the guard yet.

Dr Tiwari, too, advises caution, lest we forget. “I will never be able to forget how helpless I felt as a doctor during the second wave.”