- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Yesterday’s Gulabo, today’s Sitabo: Amitabh Bachchan as metaphor for India

Amitabh Bachchan’s cinematic odyssey is a metaphor for India. He has, like Forrest Gump, not just been present as a witness to several social, cultural and political transformations, but has had the good fortune — and the bad luck — to have been part of them, sometimes as the leading man, sometimes as the side actor, and once or twice as the sidekick.

What do you know if you know only Gulabo Sitabo alone? For those still to hit their 30s, answering this would be an exercise in believe it or not. But what follows is true. Once upon a time in India, there used to be a megastar called Amitabh Bachchan whose every film would create a mass hysteria among his fans, which was literally almost all of India. On the morning of the release of his...

What do you know if you know only Gulabo Sitabo alone? For those still to hit their 30s, answering this would be an exercise in believe it or not. But what follows is true.

Once upon a time in India, there used to be a megastar called Amitabh Bachchan whose every film would create a mass hysteria among his fans, which was literally almost all of India.

On the morning of the release of his films, people used to race to theatres at dawn, stand in queues that could be measured not in inches but kilometres. For hours they used to jostle, climb on each other, get beaten up by cops, and finally, after hours of ordeal, go back home after reading an inevitable sign: House Full.

The lucky ones, of course, knew where exactly to find the ubiquitous star of every Bachchan release — the ‘blackie’ (the cycle-stand contractor in most cases) who would sell tickets for a huge premium (black, ergo the name) to let you into a theatre reeking of smoke and anxiety.

Then, after a few agonising minutes of wait, Bachchan would make what was then called an ‘entry’, appearing larger than life because of the low camera angle. And then there would be complete mayhem for a few minutes — claps, whistles, catcalls and the sound of coins falling overhead from the box seats and the balcony.

The megastar that Generation Z would scarcely believe walked in flesh and blood on 70-mm screens, faded away in 1992 with Khuda Gawah, the last Bachchan film that ran for almost 15 weeks in what was once Delhi’s Odeon theatre.

And now there is just Gulabo Sitabo. If Lady MacBeth were a fan, she would have asked: “Who would have thought the reigning deity of big screen would one day be delivered on OTT, where you would be able to watch him at your luxury; gratis?” No queues, no blackies, no ‘entries’, no sound of jangling coins, just one more entrant to the dozens vying for audience on OTT platforms. But that’s Bachchan’s journey for you, from the erstwhile Gulabo of Indian cinema, to its Sitabo.

In many ways, Bachchan’s cinematic odyssey is a metaphor for India. He has, like Forrest Gump, not just been present as a witness to several social, cultural and political transformations, but has had the good fortune — and the bad luck — to have been part of them, sometimes as the leading man, sometimes as the side actor, and once or twice as the sidekick.

Bachchan’s serendipitous presence in India’s metamorphosis — even if temporary — from a gregarious, noisy country that never stopped, to a nation of anxious, insecure people watching his films on mobile phones is hopefully just another evolutionary episode. Tomes can be written about Bachchan. But let’s rewind to his debut to understand how he evolved with India, both on and off the screen.

Bachchan as metaphor for India

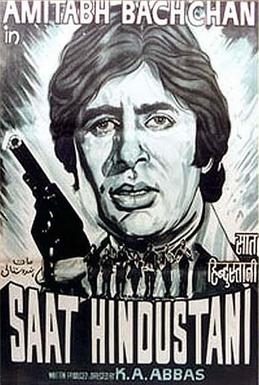

Bachchan’s first film was Saat Hindustani (1969), a middling work we have all heard about but never cared to watch. It was, incidentally, his first and last black-and-white film, setting the script of a cinematic yatra destined to witness many transitions and milestones.

Saat Hindustani was a quirky film about a forgotten era — the Portuguese occupation of Goa and the quest of some seven Indians to seek freedom from it. Its director, the late Khwaja Ahmed Abbas known more for his writing than cinema, played an inside joke of sorts on the audience in the film. In the film, all his Hindustanis were removed completely from their real life, even when the film demanded characters that were replicas of the actors. Utpal Dutt, for instance, was cast as a Punjabi farmer, and someone else was made to play the role of a Bengali revolutionary. And the joke about Bachchan was this: his character in the film was called Anwar Ali, while an actor called Anwar Ali was cast as a Brahmin revolutionary.

An interesting feature of the 60s is that cinema during those years was mostly a song-and-Kashmir affair, with an occasional evening in Paris thrown in. Its protagonists mostly dealt with the angst and pain of love and after a few fists and kicks thrown at Pran in the end, they would go on to live happily ever after. When the villain in this saga was not Pran, it was usually the colonial invader or the enemy from across the border. So, we had Manoj Kumar making Purab aur Paschim (clash of cultures) and Upkar (the 1965 war), Chetan Anand helming Haqeeqat and Dev Anand filming Prem Pujari — both about China — and Bachchan making his debut in a film about Goa’s quest for freedom.

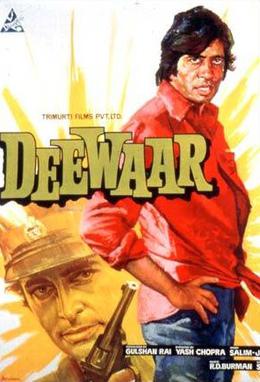

By the beginning of the 70s, India had changed completely. The colonial hangover had ended and the anxiety about the safety of the western and eastern borders had dissipated after the decisive and assuring victory over Pakistan in 1971.

Another believe it or not — there wasn’t a single blockbuster about the 1971 war! India had moved on from its colonial past and pesky neighbours to look inwards and get angry about its internal problems — unemployment, corruption, smuggling, etc. This transformation was best captured by Bachchan with his own makeover — from the idealistic Anwar Ali to the anti-hero, the angry young man called Vijay.

Since then, Bachchan has been there, done that — as a reality TV star when satellite TV was about to become the behemoth it is now; as ‘Sexy Sam’ in Seville Row suites when a post-liberalised India started living it up; as the voice of Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, and then a Modi-fied India, when political pragmatism demanded quick adjustments in both public morality and cinematic persona, and finally as Mirza Chunnan Nawab, a caricature of India, actually the world, trapped in a their proverbial havelis, eager to break free and yet trapped there by vagaries of life and death.

Bachchan’s transformation as a person has been even more interesting. From the young man who tried his luck in cinema with a letter of recommendation from the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, to Rajiv Gandhi’s trusted man and VP Singh’s Bofors punching bag; from the man who proudly once claimed that the Bachchans don’t manage contradictions but fight them, to the voice of the establishment and the majority; from the angry young man to the diplomatic avuncular presence on social media; from Manmohan Desai’s Anthony, to Amar Singh and Anil Ambani’s Anthony, Bachchan has turned with every wave and wind in India’s recent journey. But that’s a story for some other day. It is as vintage as Mirza’s haveli in Gulabo Sitabo, and as unbelievable as the tale of Indians once getting beaten in queues for a ticket to Bachchan’s cinema.