- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Why Yogi Adityanath’s trillion-dollar economy promise is a mirage

Addressing the eighth governing council meeting of Niti Aayog in New Delhi on May 27, 2023, Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath stunned the audience by declaring that he was aiming to make UP a trillion-dollar economy in five years by 2027–28. The Chief Minister obviously did not know what he was talking about. According to the state government’s Directorate of Economics...

Addressing the eighth governing council meeting of Niti Aayog in New Delhi on May 27, 2023, Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath stunned the audience by declaring that he was aiming to make UP a trillion-dollar economy in five years by 2027–28. The Chief Minister obviously did not know what he was talking about.

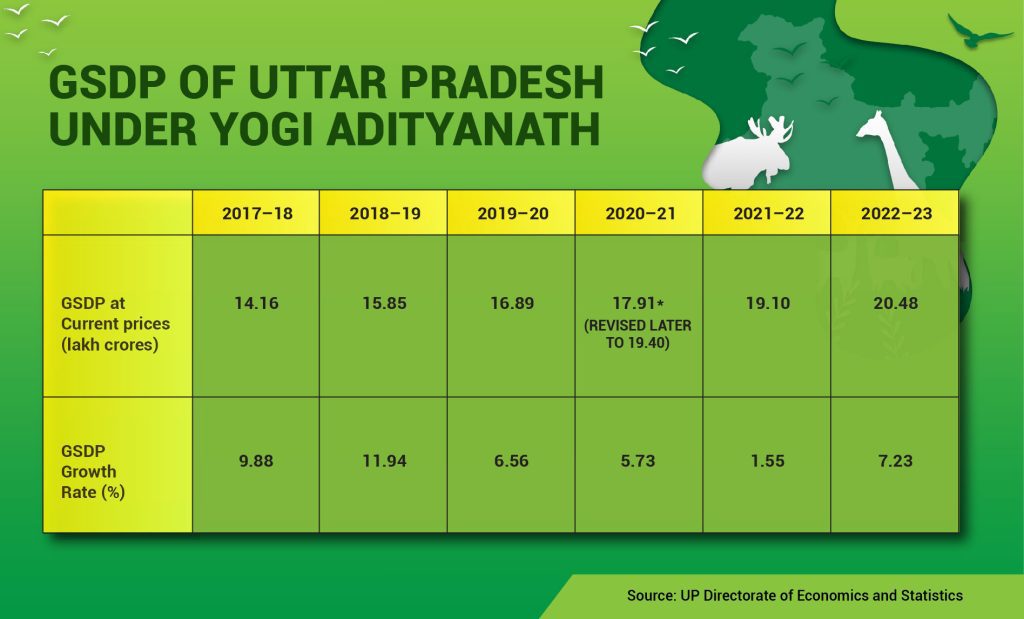

According to the state government’s Directorate of Economics and Statistics, the Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) of Uttar Pradesh for 2022–23 is estimated to be Rs 21 lakh crore. Becoming a 1 trillion-dollar economy in five years means by 2027–28 this figure should reach Rs 82 lakh crore, the rupee equivalent of $1 trillion. To reach this figure in five years, UP’s economy will have to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 31.32% a year, a level of growth never achieved in history by any Indian state.

Yogi assumed the chief minister’s office for the first time on March 19, 2017. As per UP’s Directorate of Economics and Statistics, the GSDP for the Yogi years are listed in the table below:

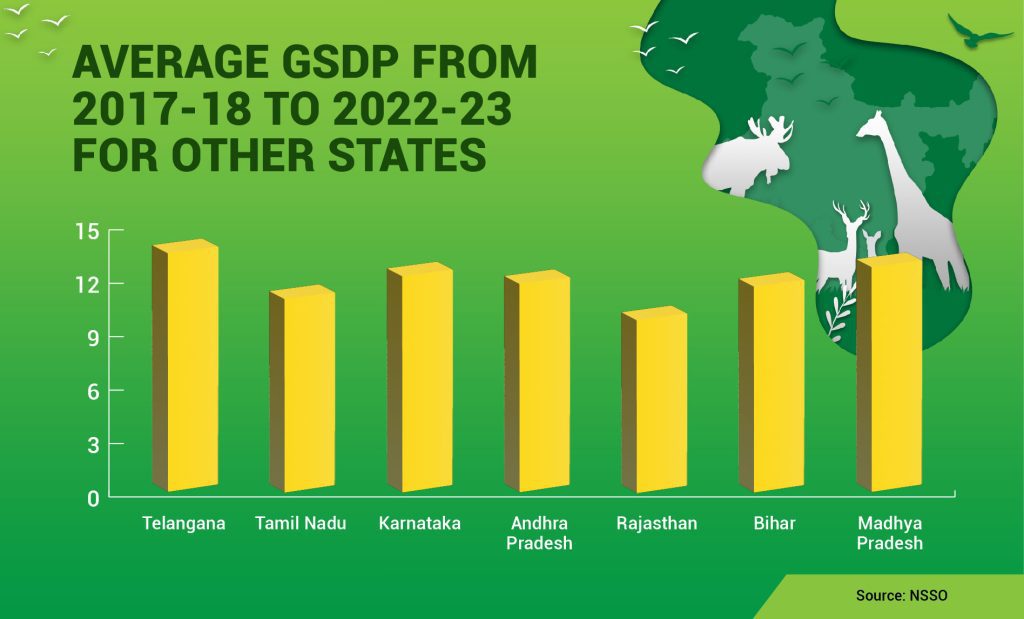

The average growth rate of UP GSDP per year has not only been quite moderate at 7.15% in the last six years under Yogi, it has been steadily on the decline, except for the post-pandemic year of recovery from a low base value the previous year. In contrast, the average GSDP growth rates of some other states in the last five years — 2018-19 to 2022-23 — have been significantly higher. For example, National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) data suggests Telangana stood at 13.90%, Tamil Nadu at 11.27%, Karnataka at 12.6% and Andhra Pradesh at 12.14%. Even among the BIMARU states, it was 10.07% for Rajasthan, 12% for Bihar, and 13.09% for Madhya Pradesh.

What ails UP’s economy

A closer look reveals that structurally in terms of the share in the gross value added, the primary sector in UP still accounted for 27.46% in 2020-21 compared to 13% in Tamil Nadu and the all-India average of around 16%. Within that, the share of agriculture, forestry and fishing was 26.06%.

The share of the secondary sector in UP was 23.63% as against 46% in Maharashtra, 45.25% in Gujarat, and 33% in Tamil Nadu. Within UP’s secondary sector, manufacturing accounted for a mere 11.70% with electricity, water supply and construction accounting for the rest.

The tertiary sector in UP had a share of 48.91%. Within that, trade had a share of 8.42% and public administration, which includes salaries to the bloated bureaucracy, came to 8.93%.

With the share of agriculture being more than double compared to manufacturing and low-wage informal clusters dominating the manufacturing, UP remains a low-wage and low-income economy.

Deceptive figure of low unemployment

In his address, Yogi patted himself on the back for unemployment being very low in UP at 4.2% in March 2023 as against the all-India average of 7.1%. This figure is also somewhat deceptive according to an Allahabad University professor who told The Federal on the condition of anonymity that this was because, in March 2023, the labour force participation in UP was shockingly low at 33.2%.

Further, the labour force participation of women in UP is 13.3%. Worse still, women’s participation in manufacturing workforce in UP is at an abysmal low of 5.7% whereas women constitute 45.5% of the industrial workforce in Kerala, 41.8% in Karnataka and 40.4% in Tamil Nadu in 2019-20, as per the Annual Survey of Industries report. Hence, among the non-agricultural population, the share of double-income families is below 6% in UP, which means relatively lesser disposable income.

The low unemployment figure in UP should also be seen in the context of high outmigration from UP for work. Migrants from UP numbered 14.4 million in Census 2011.

A senior bureaucrat, who wanted to remain anonymous, told The Federal that since underemployment and not unemployment is the main feature that marks agriculture, in UP’s economy, where the role of agriculture is more prominent, unemployment remains low. Further, when the labour force participation of both women and young men is low, unemployment also appears very low.

Jobless youth and non-working women

The labour force participation of youth of all age-groups in UP stood at 22.4% in September-December 2022 as revealed by NSSO’s Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) data. More than three-fourth of UP’s youth are out of employment. Even among those employed, the pandemic took a heavy toll. The employment rate for youth in the prime age group of 20-24 fell from 27% in the pre-pandemic September-December 2019 to 17.4% in September-December 2022 at the end of the pandemic. For young women aged 20-24, the employment rate fell from a low of 1.6% to 1% in the same period. One of the fallouts of this low work-participation is the high incidence of poverty.

High incidence of poverty

As per the multidimensional poverty index prepared by Niti Aayog in November 2021, UP has third-highest incidence of poverty at 37.79% of its population, next only to Bihar (51.91%) and Jharkhand (42.16%).

In 2023, the estimated population of UP is 23 crore and hence in absolute numbers, the number of poor in UP now would be 8.7 crore, the largest among the states in India.

Low-wage, low-income economy

This level of poverty is mainly because the per capita income in UP in 2019–20 at Rs 41,023 is not even half of the national average of Rs 86,659. Such a low purchasing power of people means very poor consumption and hence low aggregate demand which cannot spur local manufacturing.

Further, the statutory minimum wage in UP for unskilled workers is Rs 5,750 per month. It is Rs 10,988 in Tamil Nadu, Rs 10,354 in Punjab and Rs 16,170 in Karnataka.

Meagre non-farm investments

The main reason for faltering growth of UP in the Yogi years is low private investment as well as public investment. As per the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the Gross Fixed Capital Formation in Uttar Pradesh in 2018–19 was Rs 15,531.85 crore only. In contrast, the all-India figure was Rs 3,69,100 crore and the GFCF in Maharashtra was Rs 58,223.60 crore, in Gujarat Rs 60,337.38 crore, in Tamil Nadu it was Rs 37,027.82 crore, and in Karnataka Rs 27,089.62 crore.

The flow of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into UP too is negligible. As per the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT), between October 2019 and March 2023, out of Rs.14.19 lakh crore cumulative FDI flows into the country, with Rs 4.07 lakh inflow Maharashtra accounted for 29% of total FDI inflow. With Rs 3.35 lakh crore FDI, Karnataka accounted for 24% of the total. With Rs 2.39 lakh crore, Gujarat’s share was 17% in total FDI. With Rs 9,853 crore, UP’s share in total FDI flow in this period was 0.69% only.

Out of the total revenue receipts of Rs 5,70,866 crore in the 2023–24 fiscal in UP, committed expenditures like salaries on government employees was Rs 1,65,551 crore out of which the police department got Rs 35,579 crore, Rs 79,921 was for pension, and Rs 51,378 was for interest payment. So only Rs 500 crore was allocated for investment in public sector enterprises.

Industries in UP are mainly concentrated in informal and MSME clusters like in leather products in Agra and Kanpur, locks in Aligarh, black pottery in Azamgarh, woodcraft of Badohi, carpets of Basti and Mau, zari works of Bareilly and Chandauli, wooden toys of Chitrakoot and Firozabad glassware.

Unfortunately, many of these informal clusters are witnessing de-industrialisation, unable to recover from repeated blows from demonetization to the pandemic. Thanks to the yarn crisis, more than a lakh powerlooms in Varanasi, Etawah, Ambedkar Nagar, Barabanki and Hardoi, are closed. Many leather units are closed in Kanpur and Agra. Dari (carpet) works in Sitapur, Mirzapur and Mau are down, and so on.

Yogi talked proudly about the one-district-one-product scheme but his government is doing nothing significant to financially strengthen them and ease their debt burden or to help them with marketing.

Skewed priorities in UP Budget 2023–24

The Rs 6.9 lakh crore UP budget for 2023–24 allocated Rs 55,000 crore for construction of expressways, roads and metros. In contrast, it allocated only Rs 100 crore to promote start-up incubators and Rs 60 crore to promote the IT industry. The secret behind such a skewed priority is that around 20% of the contract value is siphoned off by the contractor mafia-politician-bureaucrat nexus.

The tragic irony is that UP government is spending huge money on road construction but even existing public transport services in towns are being wound up. Even big towns like Prayagraj have no public transport.

Former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh granted funds under the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission to introduce urban public bus transport service in UP towns and these deluxe buses have now almost vanished because of a lack of proper maintenance.

The long-distance bus service by UPSRTC was incurring losses because of unauthorised private bus services and instead of taking action against these illegal bus operators, ‘encounter specialist’ Yogi is not lifting a finger against them because these illegal bus services are owned by police officials, bureaucrats and even some political leaders. Yogi, on the other hand, is legalizing them by opening up key UPSRTC routes to private operators one by one.

Dark days ahead

The Yogi government has promised a trillion-dollar economy in five years while the state is reeling under power cuts. A survey by an NGO LocalCircles found in June 2023 that 94% of the households in the state are facing power cuts, a problem that UP has been facing for the past five decades.

During peak demand, UP faces a power deficit of around 5000 MW. If there has to be no power cut, the UP government has to buy power from NTPC paying Rs 5 crore per day, and with shaky finances, Yogi is not in a position to do this.

NTPC has been often threatening to cutoff power supply to the utilities in UP as their dues had mounted to more than Rs 3,000 crore and were not being cleared. UP has been buying around 5500 MW power from NTPC, and unable to pay the state has opted for undeclared power cuts. This affects not only consumers but MSMEs too. The power cuts are not only pulling down growth, but are also bound to have some electoral fallout.

Of course, in the 2023–24 budget, Rs 43,330 crore has been allocated to the energy sector.

Out of this, Rs 13,100 crore would be for power subsidy to the farmers, which has been increased from 50% to 100% for borewells, and bulk of the remaining amount would go to buy power from NTPC and very little would be left to invest to increase power generation.

On July 12, 2023, the Yogi government announced setting up of 2 thermal power plants in Sonbhadra at a cost of Rs 18,000 to generate 800 MW each, but no money has been allocated for this in the 2023–24 Budget. Currently, power consumption in the state is around 26,000 MW and it is expected to rise to 53,000 MW by 2028. UP seems to be walking into a very acute permanent power crisis.

Instead of funding power generation on a war footing, Yogi’s budget priorities are different.

A sum of Rs 2,500 crore has been allocated to make preparations for Maha Kumbh Mela in Prayagraj in 2025, Rs 1,000 crore has been allocated for Dharmarth Marg project. The project involves developing roads to connect religious and spiritual centres. Here too, it is only posturing and though Uttar Pradesh saw a footfall of 24.87 crore tourists in 2022, the tourists found even basic facilities lacking.

Yogi might not be personally familiar with matters of economy, given his modest background as a religious mutt head. But it is surprising that there is not a single senior bureaucrat in Uttar Pradesh who can speak truth to their political boss. Neither rhetoric nor sycophancy can deliver growth.