- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Why women saddled with caregiving need support, breaks

Rajini K, a 63-year-old homemaker, barely steps out of her house. She is so caught up with taking care of her ailing mother-in-law (87) that there is with no time left for herself. Rajini’s life revolves largely around her mother-in-law — from ensuring she is fed on time to getting her to change her clothes after she is given a bath and making her wear a diaper at night. “I...

Rajini K, a 63-year-old homemaker, barely steps out of her house. She is so caught up with taking care of her ailing mother-in-law (87) that there is with no time left for herself. Rajini’s life revolves largely around her mother-in-law — from ensuring she is fed on time to getting her to change her clothes after she is given a bath and making her wear a diaper at night.

“I have always been a homemaker since I got married almost 40 years ago. So when my father-in-law began to ail almost a decade ago, I automatically became his caregiver,” she says.

Ten years after her father-in-law passed away, Rajini has donned the role again, this time for her mother-in-law. “I do it willingly, but I also wish that I got a small break from my routine,” she says.

Rajini is among the countless women in the world who take up the responsibility of taking care of an ailing aged relative or someone who needs assistance in their sunset years.

Traditionally the ones taking care of the household, women are often the ideal caregivers because they are often healthier and outlive their male counterparts.

How caregiving is considered women’s job

A survey on ‘Role of Family in Caregiving’ by HelpAge India 2019 across 20 cities has revealed that female caregivers outnumbered men when it concerned activities of daily living (ADL) for elders. In a most of the cases, it is either the daughter or the daughter-in-law who does it.

The survey has also shown that across the nation, 28-68 per cent of daughters-in-law are providing care for Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) that includes preparing meals, helping with phone and housekeeping, medicines or managing money. The help by sons for such care ranged between 10 and 51 per cent, the survey found.

Anupama Datta, head, policy research and advocacy, HelpAge India, tells The Federal that the findings have been uniform across tier 1 and tier 2 cities, with women taking up different kind of roles, while men manage the financial responsibilities.

“The emotional and physical stress were evident and while they said they were happy taking care, they also said they would like some help or get a break from the task,” she says, adding that the study highlighted the lack of support from other family members, society and others.

The picture is no different in the western world. An earlier study in the United States found that the burden of taking care of an older relative falls on female relatives, and that 14 million of them in the country are actually dependent on the women in their families.

In India, the growing number of the aged will continue to pose a challenge. As per a report by the United Nations Population Fund in 2017, 12.5% of India’s population will be 60 or older by 2030 and this number will be one-fifth or 20 per cent by 2050.

Southern states of Tamil Nadu and Kerala have the highest number of ageing people with over 11 and 12 per cent respectively.

Caregiving for the ageing population is all the more challenging with at least 4 per cent of the population suffering from dementia and running a high risk of contracting stroke and Parkinson’s disease.

However, the compounding factor is also the lack of geriatric services. While Tamil Nadu led by example by establishing a specialty section at the General Hospital, Madras, in the 70s, Dr VS Natarajan, who led the initiative, says the number of geriatricians is way short of the requirement.

“The ones are all concentrated in the cities whereas in rural areas there is no awareness and the disease burden among the ageing population is not addressed.”

The state needs at least 5,000 geriatricians, but there are hardly 40 of them, he says. This means that the ageing population is going to be ailing without care, mounting the burden on the family.

Burnout is common

Sathya Dhilip, who had been taking care of her father for several years before he passed away at the age of 93 in 2017, says that there were days when she thought she wouldn’t be able to take it anymore. A working woman, she recounts how playing too many roles got the better of her.

“I hired a help for the day, but when she wouldn’t turn up, I had to take leave from work and attend to him. The help would not feel comfortable washing his soiled sheets as well, and in such times, I felt that even hiring a help wasn’t helpful to cope with the responsibility and the stress,” she says.

Dr R Sathianathan, former director, Institute of Mental Health, Chennai, says that burnout is always a fallout of overburdening the woman and taking her role and responsibility for granted.

“This assumption that the woman has to step in for care stems from our traditional belief system where a woman has always been the caregiver — she feeds the family, does household chores and takes care of them. She is also seen as more empathetic and caring. However, it can be burdening when there is no respite for her, especially when the person is bedridden or has a problem like Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease, where there is memory loss,” he says, adding that in the long run, unchecked burden on the woman can cause anxiety and depression.

Vimala, a 54-year-old insurance agent who stays with her mother Vedavalli, who is coping with Parkinson’s Disease, describes how her life has changed since she began taking care of her mother.

“My whole day is planned around her. I have quit my part-time job as a teacher too in order to attend to her needs. While she is very appreciative of things done for her and is also coping with the condition, there are times when she feels dizzy or experiences a sharp pain in her spine, leaving her incapacitated. She is totally dependent on me during these spells. And she is unmanageable during those times and can get very moody, causing a lot of stress for me,” she says.

Rising costs of care

Rajini says that she had hired help for her father-in-law and entrusted her with various duties, including giving him medicines on time to ensuring he is taken to the restroom.

“However, it is not as easy as it seems. I had to cook for the nurse as well and give her tea and snacks while she is on duty,” she says.

While caretaker services are available at ₹650-₹2,000 per shift, it may not be affordable for all.

However, these services can help families seeking elderly care, explains Dr Renuka David, managing director, Radiant Medical Services that focuses on south India.

“Assisted living, like in the western countries, has not picked up in India. But there is considerable demand for services catering to assisted healthcare at home,” she says, explaining that there are different kinds of paramedic courses conducted by institutions whose duration ranges from 3-6 months up to two years.

“We also ensure that they (nurses and caretakers) undergo another round of training by our agency to groom them further,” she says.

David also points out that these services are sought not just for illnesses but also for age-related requirements. “We have demand especially from those who live in the same vicinity as their parents who are living independently, but they need help with food, medicines and changing their diapers.”

The assumption that the woman has to step in for care stems from our traditional belief system where a woman has always been the caregiver.

Anu Chandran from ANEW, an organisation that trains caretakers, says that women and caregiving are deeply linked.

“We have male nurses too, but I guess for a woman, it comes naturally to care and we don’t have to teach them to be sympathetic,” she says.

Anu says that in the last two decades there has been a lot of demand for such services in Chennai. “A spurt in the number of nuclear families has led to a demand for such paid services,” she says.

Solutions, anyone?

While experts say that support groups can help, Sathya asks if the concept has evolved in the country.

“We often question ourselves if we have to open up or vent out to strangers or let them in on a discussion about my personal struggle,” she says.

Hospitals across the country are forming support groups for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s that can help families share their stories and connect with others who are undergoing a similar turmoil.

While the issue is linked to a sociological setup, questions are also raised on the boundaries of duty and care. If the daughter-in-law prepares tea for the father-in-law or mother-in-law, is it care or duty?

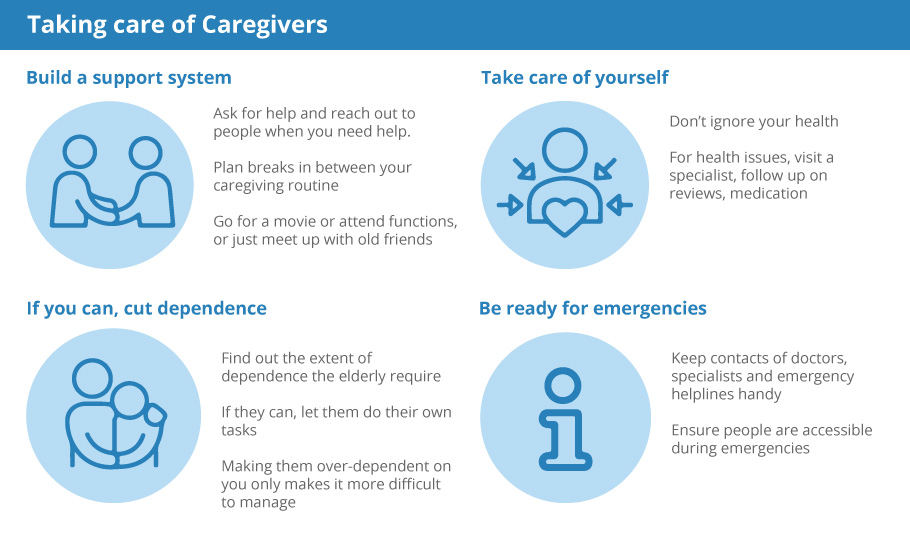

Experts also suggest that people should plan ahead, anticipating the burden of caregiving, to avoid being overwhelmed when the time comes. If overwhelmed, it is hard for the person to ask for help, they say.

Taking up activities like painting or yoga classes can also help. A website dementiacarenotes details how a relative, family or friend can help caregivers, especially by being alert about the health of the caregiver, and helping spot burnouts.

Awareness among close family members and friends can also help. Little gestures like sending caregivers gifts occasionally, can cheer them up.

Dr Sathianathan says institutionalised setups or day care centres can be a solution too. “However, distance can become an issue for those who want to seek such services,” he says.

The stress can also result in abuse, points out Anupama. “That is why there is a need to rebuild dialogue in the family and it is important to appreciate and acknowledge the work done by a caregiver,” she says.