- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

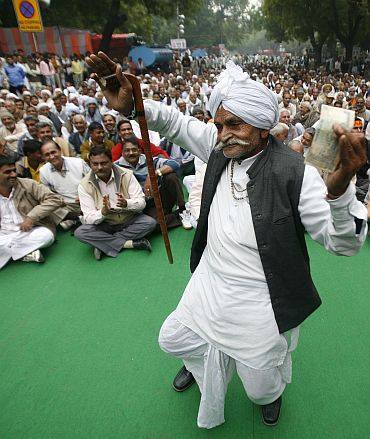

Why the unsparing khaps still enjoy popular support

On April 17, 2018, Ishapur Kheri village in Haryana’s Sonepat district made national headlines after a khap panchayat banned girls from wearing jeans and using mobile phones. Reason: The informal body of village elders believed mobile phones and jeans were the main culprits behind girls eloping with boys. Referring to an incident wherein three college girls had eloped with boys, one of...

On April 17, 2018, Ishapur Kheri village in Haryana’s Sonepat district made national headlines after a khap panchayat banned girls from wearing jeans and using mobile phones. Reason: The informal body of village elders believed mobile phones and jeans were the main culprits behind girls eloping with boys.

Referring to an incident wherein three college girls had eloped with boys, one of the supporters of the order contended, “By wearing modern clothes like jeans, they [girls] attract unnecessary attention. And using mobile phones, they get in touch with the boys and make plans to elope.”

This particular order, however, was not issued for the first time. Numerous such incidents have been reported in the last few decades where absurd orders have been passed by various khap panchayats, but they continue to be hailed by most of the villagers, however harsh they sometimes are.

The worst that comes to mind are the horrifying images of murdered couples who married for love outside the community or against its diktats that are mostly anti-women.

These khaps, despite their controversial past, have made a massive comeback in popular consciousness following the ongoing farmers’ protests against the new farm laws. A series of mahapanchayats with massive gatherings held in various parts of Haryana, western Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan have been so far successful in keeping the momentum of the protests alive.

The khaps rallying behind the protesting farmers has sent the central government into a tizzy since no political party can afford to upset the khaps or the massive votebank that comes with them.

It is for the same reason that farmer leaders are now underlining the importance of khap panchayats, saying that this is precisely what these traditional bodies do—resolve disputes over land and life of rural villagers.

But before this new-found relevance, khap panchayats have been in news mostly for ordering brutal punishments and ‘honour’ killings. As recently as September last year, a young couple in Rajasthan’s Sikar district was allegedly made to bathe naked in front of hundreds of people for their alleged affair.

In October, a khap panchayat, this time in Rajasthan’s Chittorgarh, allegedly ordered a 12-year social boycott of an elderly man for opposing child marriages.

What are khap panchayats

Khap panchayats are traditional, informal local judicial bodies active in states such as Haryana, northern Rajasthan, the rural belt of Delhi and western Uttar Pradesh. They are part of the rural social setup and have roots that lie deep in the past.

The main work of traditional panchayats revolves around issues threatening the peace of villages, disputes over property and inheritance and sexual/marital transgressions. For them, the four-strong pillars of rural society are unity, honour, community and brotherhood. And any incursion of unfavourable practices creates an adverse environment.

The punishments that traditional panchayats hand out for transgressions have been archaic. These could be fines (nominal or substantial) to be deposited in a common fund of the panchayat, ritual atonement, public humiliation (ranging from blackening of the face to rubbing the victim’s nose in dust, shaving off hair, and sometimes even dipping the victim’s nose in urine), forcing them to host a feast, subjecting the victim to a beating, forcing them to visit the elders in the village and give a public assurance not to ‘err in future’.

Khaps are also social-political groups comprising upper caste and elderly men who are united by geography and caste. They are considered to be upholders of village norms, custodians of rural culture and guardians of public morality.

Khaps are found mainly in regions where communities of Jats and Gurjars are in majority.

Since time immemorial

‘Khap’ is an ancient concept that has written references from the Rig Vedic period. It is commonly believed that they came into existence sometime around 600 AD. Ancient society had organised itself into clans or under the panchayat system. A clan at that time was based on one large gotra (tribe) or a number of closely related gotras.

A number of villages grouped themselves into Guhaand. A number of Guhaands formed a ‘khap’ (covering an area equal to a tehsil within a district) and a number of khaps formed a ‘sarva khap’ embracing a full province or state. For example, there is a ‘sarva khap’ each for Haryana, western UP, Malwa region of Rajasthan, etc.

Decisions relating to the activities of these social groups were made under the aegis of and with the consensus of a council of five elected members.

In times of danger, outside invasion or other kinds of crises, the whole clan rallied under the banner of the panchayat and a leader would be chosen by the assembly.

Each clan has a hereditary head man called Chaudhry. However, some of the Jat clans name this position wazir (secretary). The clan head is also the head man of khap council. In the case of Haryana, the head of khap panchayat is elected in a formal manner through consensus.

Initially, khap panchayats were believed to have strong political ideologies, established values in the society and made major contributions to the country.

In the first sarv khap panchayat after Independence in 1950, resolutions were taken against dowry and spending too much money on weddings so that people would not consider girls as a burden and would rather invest in their education.

Some other resolutions taken by sarv khap panchayats were mostly confined to social and political issues and were easily acceptable to the people.

For instance, people would donate to the national defence fund in the wake of the Chinese aggression, help the government in forming a village volunteer force and farmers to grow more food etc. The panchayats were supposed to strive to eliminate distinctions and barriers among different castes and promote the establishment of colleges for women.

But over the last few decades, some khaps started intervening in matters of marriages in families within its jurisdiction. Resolutions such as ‘inter-caste marriages are strictly taboo’, ‘no one is allowed to marry outside their caste’ have caused much consternation and chaos among the communities and outside.

P Sangwan, an independent researcher based out of Haryana, says, “Khap panchayats have thrived because elected panchayats failed to deliver effectively on issues related to society at large. This space was occupied by the khaps. They may have been reformist in the past but instead of focusing on issues related to female foeticide, dowry and alcoholism in the society, their sole concentration now is only on inter-caste/and same gotra (clan) marriages.”

Illegal yet running

Khap panchayats perform mainly three types of functions, adjudicative, legislative and executive. They are ‘self-proclaimed courts’ managed by the elderly people of dominant castes which are famous for ‘self-styled decision making’ and sometimes are also called social dictators. In other words, non-constitutional and illegal bodies.

The Supreme Court in 2018 declared khap panchayats “illegal”, saying that no assembly can interfere in a marriage between two consenting adults. A three-judge bench, headed by then Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra, said, “The punitive measures to deal with such an unlawful assembly will be in force until a legislation comes into force.”

However, the state and local administration do not interfere in the functioning of khaps, avoiding any confrontation with them even when the courts rule against them, which is a pointer to not just the entrenchment of the khaps in rural society, but their political influence as well.

Rahul Sharma, superintendent of police of Rohtak district in Haryana, tells The Federal, “Khap panchayats exist and people follow them. We cannot stop anyone from following somebody. Incidents happen but we get no evidence against the khaps or khap leaders. People don’t speak against khaps.”

Every politician eyeing the Jat vote bank tries to justify the khaps. Former Haryana chief minister Bhupinder Singh Hooda and Aam Aadmi Party’s Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal are two prime examples of such politicians among others.

According to Hooda, khap panchayats were akin to ‘NGOs’ and a part of Indian culture. Kejriwal famously said that he saw no reason to ban these bodies, as they serve a “cultural purpose”.

Recently, terming khaps as “custodians of culture”, Haryana CM Manohar Lal Khattar said they were like “parents minding the children” and often take swift decisions on matters in which the courts are silent.

The great ‘bhaichara’

The concept of bhaichara (brotherhood) means that members of the same generation are classified category siblings (bhai-behan) and cannot marry. This idea of ‘bhaichara’ starts from the village level and continues up to the khap level.

There exist three types of bhaichara. Village bhaichara, in which members of one generation are treated as brothers and sisters as originating from a common ancestor and, therefore, related by blood. Another is gotra or clan bhaichara, in which all members belonging to the same gotra in the same caste are treated as brothers and sisters, even if they belong to different villages.

The last is families belonging to the same caste but with different gotras, which do not marry in the villages of the single gotra-khap because such khaps are numerically dominated by a single gotra. All other persons living in a khap area, irrespective of their caste or gotra, treat each other as brother and sister. Khap bhaichara is normally emphasised in the khap panchayat.

Tekram Kandela, head of Kandela khap, says, “The marriage within the same gotra, or same clan, or same village is not possible because, in a clan, everybody is a brother and a sister.”

“Moreover, the honour killing diktats have never been given by sarv-khap panchayats. This can be a diktat of a particular khap but sarv khaps always respect women and do everything to save and educate them. But we also look at the area and how the people are in that particular area. That is where the ban on some particular type of clothes comes from,” he explains.

But why do people comply

Rajinder Singh, a sociologist based out of Haryana, says, “People who have a firm belief in such organisations give many facts in their support. Khaps deliver verdicts in disputed matters in one sitting while the courts drag the cases for years. In many cases, innocent people face harassment in the courts and by the police. But in khaps, since everyone is known (to each other), they cross-check everything to ensure neutrality.”

Members of khaps, he adds, are senior citizens and are considered experienced and custodians of culture. “So nobody goes against their decisions. These institutions have a very old history owing to which people have a great trust on them.”

Also, the fact that khaps do not involve any money makes this system popular. “They are less time-consuming and there is a direct negotiated settlement between both parties before a large audience that includes persons of authority in the panchayat. They also help maintain social order among people of different castes and act as an important agency of social control.”

Sometimes, however, the decisions of the khaps militate against the modern laws of the land, not to mention violation of human rights. This creates a contradiction between the traditional system of dispute resolution and modern institutions such as the judiciary and the administration. But such decisions work well with the local population.

Vishal Kandela, a farmer from Kandela village, says, “Khap panchayats never worked against us or would give decisions which are bad for the village in the long run. All the orders given by them have a larger impact on the villages and the decisions they take have saved us from a lot of blunders in the past.”

This, Tekram Kandela says, is what people sitting in urban areas don’t understand. “They have no idea about the situation here in the villages. We make decisions for the betterment of villages. Our decisions unite the villages and increase bhaichara.”

DR Chaudhry, an author who closely followed khap panchayats, says, “Khap leaders are usually strong and command respect not only at a local level but also from politicians. They give voice to the voiceless. But to my surprise, khaps in the medieval age were more liberal and forward-looking as compared to the present-day khaps.”

He adds, “Earlier, reform and settlement of harmony in society used to be the core issue of khaps, but the last few incidents in Haryana, individuals were targeted to settle scores or due to political rivalry.”

On the future of khap panchayats, Chaudhary says, “With the changing times, khaps need to be relevant with the modern age and strike the right chord with the society, instead of exerting undue force.”

Ask the young girls of Ishapur Kheri village and they say no one knows better what kind of ‘undue force’ they face every day.