- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Why Sri Lankan Tamils feel Deepa Mehta’s Funny Boy ignored their history

For a young boy from a Tamil family in the Colombo of 1970s and 80s, Arjie struggled to understand why boys were not allowed to wear lipstick. Or why his preference to dress up as a girl than to play cricket with his brother made him ‘sissy’ or a ‘funny boy’. If all that was not enough to make Arjie’s life difficult, the escalating political tensions between the minority Tamils and...

For a young boy from a Tamil family in the Colombo of 1970s and 80s, Arjie struggled to understand why boys were not allowed to wear lipstick. Or why his preference to dress up as a girl than to play cricket with his brother made him ‘sissy’ or a ‘funny boy’.

If all that was not enough to make Arjie’s life difficult, the escalating political tensions between the minority Tamils and the majority Sinhalese made the young boy realise what it meant to be a gay in a society and family that didn’t embrace differences outside of societal norms.

Not that things are any different for boys and girls like Arjie growing up in most parts of the world even today. Much like India, sexual acts between same-sex individuals was illegal in Sri Lanka in the 80s. It is a criminal offence even now in Sri Lanka. In fact, it is one of the 69 countries in the world that has laws that criminalise consensual same-sex acts.

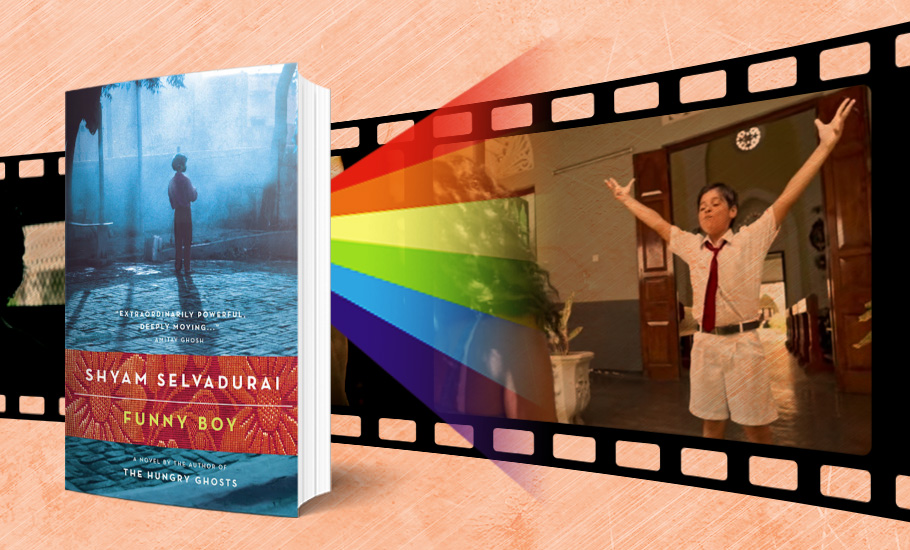

So when Indian-Canadian filmmaker Deepa Mehta set out to explore Arjie’s journey in her latest film, Funny Boy, based on the eponymous 1994 novel by Shyam Selvadurai, expectations were high.

However, it has drawn more controversy than praise. Mehta’s Funny Boy finds little acceptance among Sri Lankan Tamils or even the LGBTQ community.

Misrepresentation and cultural erasure

“The film’s main problem is misrepresentation. The abusers played the victims [roles],” says Angel Glady, a theatre activist and core member of Queer Tamil Collective, which is leading the protests against the film in Canada.

The film, Glady adds, has a majority of Sinhala actors. “It’s like portraying the plight of Blacks using White actors in brownface (wearing make-up to imitate the appearance of a non-white). The film claims to show our plight that has no representation of Tamils. We are questioning that.”

“Mehta uses an old Tamil film song ‘Paattu paadavaa…’ (from Thaen Nilavu, 1961) over and over again in order to increase the Tamil word count in the film,” Glady laughs.

Following the protests in Canada, activist and founder of ‘Kattiyakkari’ Srijith Sundaram says the LGBTQ community in India will oppose its screening in queer film festivals.

“Mehta has done equal damage to the queer Tamil community through this film,” Sundaram adds, drawing a comparison with Mehta’s 1996 film Fire, which drew the ire of Hindu fundamentalists.

Flawed political understanding

Writer and translator Vickneaswaran, who migrated from Sri Lanka to Canada in 2013, says besides the technical faults in the film, the director lacked basic understanding of the region’s politics.

“In one scene, a television news piece shows that the [Tamil] Tigers have attacked ordinary Sinhalese in 1983. This is completely wrong. Before 1983, neither the Tigers nor Tamils had attacked ordinary Sinhalese people,” he says, adding that the violence was mostly between the Tigers and the Sinhala army.

“The film tries to show that the attack by Tigers on ordinary Sinhalese people instigated the latter to retaliate against Tamils. It tries to prove that the Tigers made the first attack on ordinary Sinhalese. However, it is true that after 1983, the situation changed and both ordinary Tamils and Sinhalese started attacking each other,” he says.

Vickneaswaran, however, feels it’s possible that the filmmakers may have been compelled by the Sri Lankan authorities. “If the film crew wanted it to be shot/screened in Sri Lanka, it’s possible the authorities demanded such a narrative to be included.”

Moreover, he adds, even while reading the novel, one gets the feeling that the author never “felt quite Tamil”. “I think that could also be a reason why he remained silent on such flaws in the screenplay.” To put things in perspective, Selvadurai is a Sri Lankan-Canadian who was born in Colombo and is of mixed Tamil and Sinhala heritage.

Interestingly, the screenplay of the movie was written by both Selvadurai and Mehta. Even though Selvadurai’s novel gained iconic status for its representation of the queer Tamil community back in the 1990s, many like Vickneaswaran found the film extremely disappointing.

On the cultural front too, Vickneaswaran points out that the film got it totally wrong when it shows Tamils falling at the feet of fellow Tamils at all times. He says this is done only during weddings by the couple and that too only to elders to seek their blessings. “The culture of falling at the feet of fellow people happens among Sinhalese Buddhist monks,” he says.

Similarly, he adds, the Shaivites in Sri Lanka don’t draw two lines with holy ash on their forehead as shown in the film. “They smear the ash all over the forehead with their fingers.”

Diaspora portrayal

Norway-based Sri Lankan Tamil novelist Kuna Kaviyalahan says another issue with the film was how it portrayed the Tamil diaspora.

“The film tried to show why and how the Tamil diaspora was formed. But the thing is, if the director had approached Sri Lankan Tamil writers like us, she could have prevented errors in the screenplay and dialogues,” he says.

However, while many are angry with Mehta for not casting enough Sri Lankan Tamil actors, Kaviyalahan says the “Tamil film industry is still in a nascent stage there”.

“In Sri Lanka, the Sinhala film industry has grown well. In the 60s, some Tamils acted in Sinhala films and some Tamil films were made with the support of Sinhala film industry. During the civil war, about 5-10 film personalities were Tamils. There are some short films and documentaries. However, Tamils there still do not have the ways and means to make full-fledged feature films. It is possible that the film crew may have found it difficult to get Tamil actors,” he says.

Director Deepa Mehta herself has clarified that she couldn’t use Tamil actors due to their unavailability.

Kaviyalahan though has issues with the language used in the film. “It is wrong to expect that the dialect spoken in Jaffna would be the same as in other parts of the island where Tamils reside.”

“A section of the elite Tamil families lived and spoke like that (in the film). Even Selvadurai is of mixed heritage. It is said his father was a Tamil and mother was a Sinhalese. So criticising him for not standing by Tamils is also not right,” says Kaviyalahan.

He also adds that since it is a period film, the viewers must not compare the situation then and now.

“The film was set in the 80s. The times were different then. Like in India, before 2000, discussions about LGBTQ were not held in the open. However, we cannot say that gay relationships did not exist then.”

But have things changed in Sri lanka now?

Observers feel that Sri Lanka has still not opened up. “Forget about the war years. Even today, transgenders are unable to form a community like the ones we find in India. The same happens with same-sex couples,” says Sri Lankan Tamil documentary filmmaker S Someetharan, who is in Chennai, although he admits that there are a few individuals who work as independent activists sans organisation.

More than the war, it is the culture that doesn’t give space for these issues, he says. “Both Sinhala and Tamil communities are orthodox.”

“As a novel, Funny Boy’s storytelling brought to the fore one of the most silenced Tamil-speaking experiences to a global audience.

Selvadurai’s semi-autobiographical novel was received well in the international community and won the Lambda Literary Award for Gay Fiction and Books in Canada First Novel Award. The portrayal on film, which normally should make a larger impact, however did not get the same reception.

Writing in ‘Maynmai’, a multi-ethnic and multi-racial platform established to respond to attacks on asylum, Yalini Dream and Angel Queentus say: “Despite ancient queer, trans, and intersex Tamil and Muslim histories, the space for our communities has violently narrowed due to persecution and disinformation advanced by colonisation, casteism, religious patriarchies, authoritarianism, economic exploitation, disaster capitalism, and war.”

Yalini Dream is a Sri Lankan Tamil performing artist while Angel Queentus is the founder of Jaffna Transgender Network.

“By the time of Funny Boy’s publication in 1994, a false binary had emerged that there were no real LGBTQI+ Tamils or Muslims, and if you were ‘Vityasamana’ or ‘different’ or ‘funny’ in this way, you were influenced or converted by Western society.”

“Though Funny Boy lacked insight into the caste, religious and class dynamics that impact the most persecuted within our communities, Shyam Selvadurai’s words subverted this false binary and opened a desperately needed space,” they write.

Thanuja Singam, the first Sri Lankan Tamil transgender to write her autobiography, is also the first person to apply to the Sri Lankan High Commission in Germany for changing her sexual identity from male to female. But her journey to become a woman wasn’t that easy as her autobiography—published by Chennai-based Karuppu Pradhigal—says.

“In Germany, the laws pertaining to the welfare of transgenders were enacted only in 1981. In Sri Lanka, it was during the 1990s that such laws came into being. It is to be noted that in the South Asian region, Sri Lanka is the only country which acknowledged transgenders by issuing them a new birth certificate mentioning woman, since they are converted to transgender. These are legal protections. But if you ask if we have protection in society, the answer is no. While transgenders who have undergone sex conversion surgery at least have legal protection, even that is lacking for people who are in a same-sex relationship,” she says.

Refusing the terminology ‘third gender’, Thanuja explains that the word transgender is used to refer to a person who has transformed from a male to female (or vice versa).

“We like to be recognised as women. So why should there be first, second and third categories of gender?” Thanuja asks.

During the war, she says, men who realised that they have ‘feminine qualities’ were unable to come out openly because they wanted to save their families. People were displaced, disappeared, killed and became refugees.

To be precise, Thanuja says, they weren’t in a situation to identify themselves as transgenders.

It is in such accounts and history that the pain and plight of hundreds and thousands like Arjie lay buried even years after the violent civil war in Sri Lanka that dragged on for nearly three decades.